Plein air painters confess a deep love for the land. And even if they don’t say it, their paintings show it.

In general, plein air painters embrace the “leave no trace” aesthetic of enjoying the great outdoors. Everything brought with the visitor leaves with the visitor at the end, so it’s as if no one was there. That’s all good and appropriate. But for plein air painters who want to be sure that their passion for the landscape doesn’t result in harming it, there’s no substitute for doing a little research.

The simple truth is that some of the most spectacular views in our country’s national and state parks are being loved to death. Trails widen and cause erosion, visitors go off trail in an effort to see new sights or to get away from the crowds, and in the worst cases, people engage in careless littering or even downright vandalism.

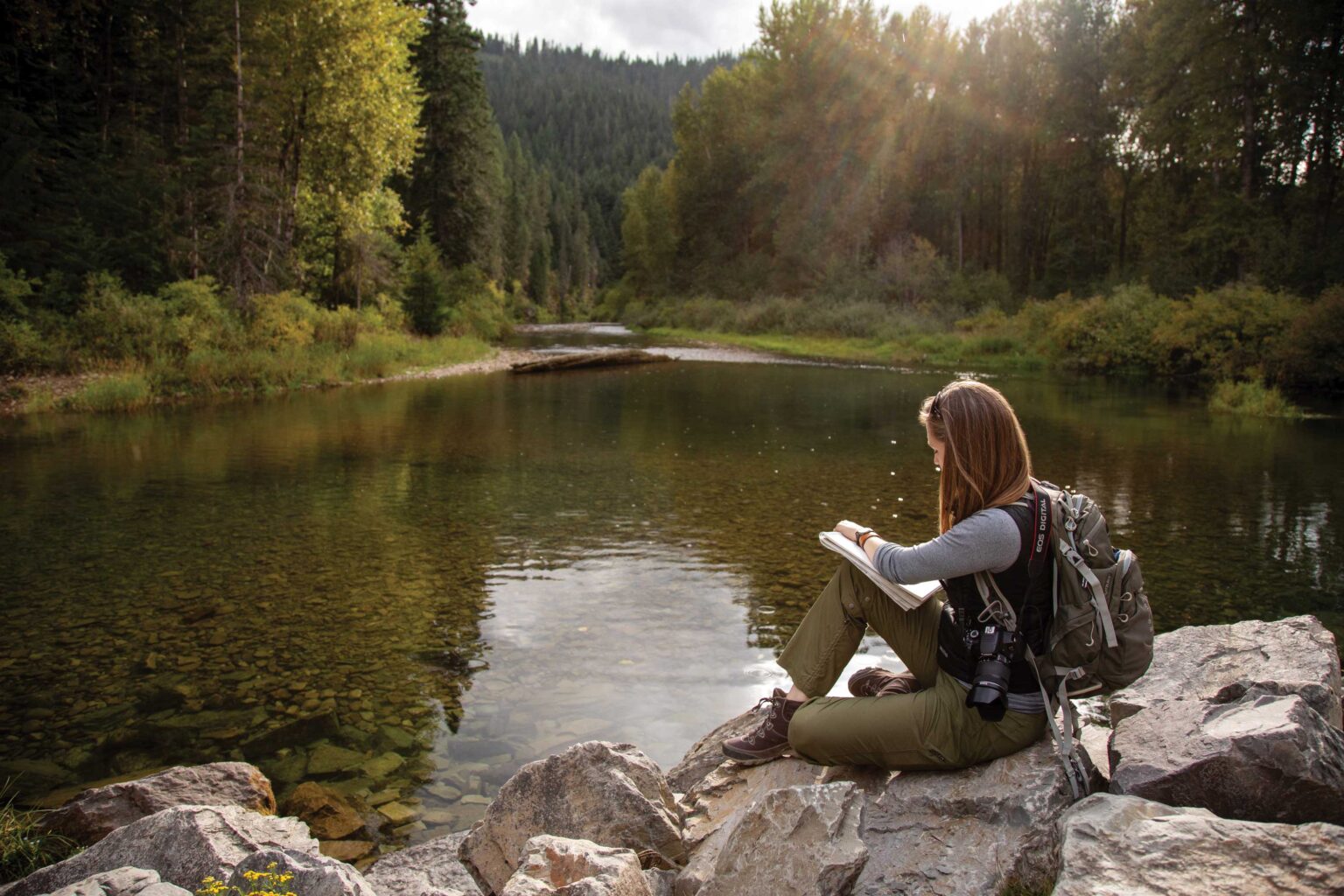

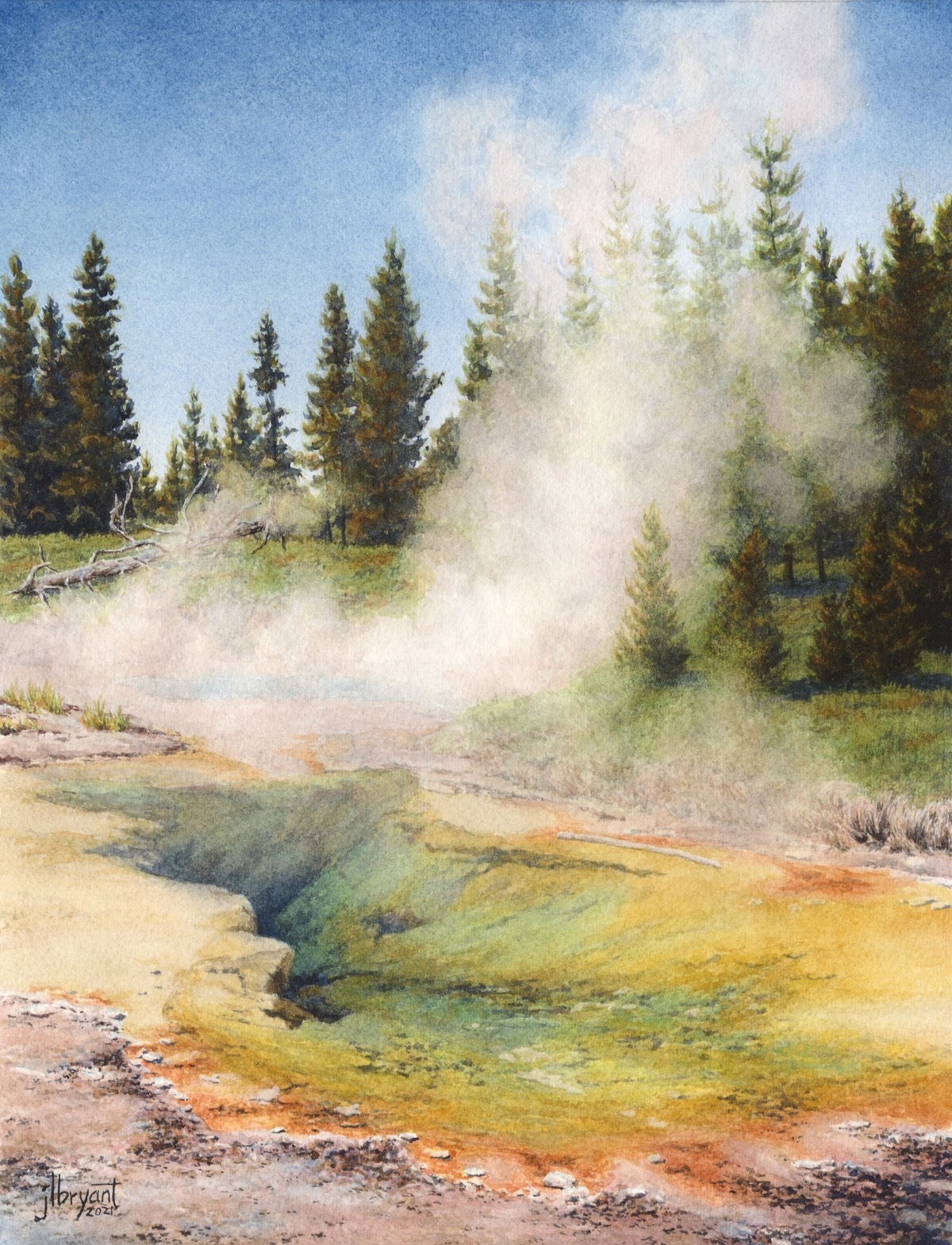

“Because there are so many people going out and enjoying the outdoors, you can find human impact anywhere you go,” says Idaho watercolor artist Jessica L. Bryant. “In Joshua Tree National Park, people were taking down gates and driving across what was a preserved and intact ecosystem. They were not just destroying plants but doing donuts in the desert, preventing anything from growing there for a long time. In a park by me, I come across campsites littered with toilet paper, Red Bull cans, and used shotgun shells. Why, I’m not sure. Maybe it just doesn’t bother some people.”

Unfortunately, the issue is not just reining in the few who are oblivious or wrongheaded. Some parks have limits on the number of visitors allowed per season — a necessity given that, according to the National Park Service, our parks get more than 300 million visits per year. It’s great that people enjoy this nation’s wonderful natural beauty, right? But anyone who fails to realize the impact of too many people on a finite amount of green space need only visit a park in an inner city to see what it means to love nature to death.

Understand the Unique Ecosystem

It’s tempting for plein air painters to see themselves as somewhat exempt from strict rules, given that renditions of the scenes in parks help foster a love and appreciation for these potentially vulnerable ecosystems. Artists capture these landscapes before they change, and they allow folks who may not ever be able to visit them to experience their beauty. And how many plein air painters are out there, anyway? How can such a small subpopulation do much damage?

“You are not the only one who is doing it,” says Jim Ekins, Associate Extension Professor and Area Water Educator for the University of Idaho, in Coeur d’Alene. “There are also writers, photographers, park rangers, researchers — it’s more than just a few artists. Your little bit of impact accumulates pretty quickly.

“But there are ways to get it done, and do so with limited impact. The idea is: we are going to have some impact, but if we can keep it within the natural variability, then we are going to be okay. There are always disturbances to the ecosystem. But if the impact is greater than the ecosystem can tolerate, the effects are going to be there for a long time. So stay in the natural range of disturbance. Understand the ecosystem enough so our presence is no greater than other animals. If we do that, the disturbance will go away rather quickly.”

Understanding the ecosystem simply requires stopping by the park’s welcome center and reading some information, or asking a park ranger. It’s not hard, and it’s likely to improve your visit in some other way. Take the time to understand in what ways the ecosystem is delicate. And don’t trust your eyes. In some spots, one can see plants and animals survive some of the most punishing conditions on the planet. How could a painter with a tripod damage a windswept desert, or a rugged mountaintop?

“Just 20 foot stamps will kill a lot of alpine plants, and much fewer will have an impact,” Ekins says. “They seem tough because they live in an extreme environment. But the cold, wind, and snow keep animals and people out of there, so they are not very resilient in terms of human use. If you must go to that one spot for that one particular angle, be cognizant of your impact. You may need to take a photo from your exact spot and do the painting from a nearby trail.”

Deserts may be even more delicate. “You may be in a barren area, in a desert ecosystem, and think you can’t do any damage to a bunch of sand with not many plants, but in the desert, the top of the soil is covered with a cryptobiotic soil crust, a living thing that keeps the soil intact and reduces erosion from wind and water,” says Bryant. Ekins adds, “It’s a very delicate surface crust made of both fungi and bacteria — like lichen, in a way. You should know that it’s going to take a century before that crust grows back if you disturb it.”

Eyes may roll at the notion of curtailing plein air painting for the sake of a scarce millimeters-thick soil crust, but perhaps the owners of those eyes need to know that destroying nature when the National Park Service specifically advises against such behavior is illegal. You won’t go to jail for walking off trail, but the rule-followers out there should still take note. The code of federal regulations prohibits “polluting or contaminating park area waters or water courses,” and “possessing, destroying, injuring, defacing, removing, digging, or disturbing from its natural state: Plants or the parts or products thereof.”

Leave No Materials Behind

So what’s a responsible plein air painter to do? The doctrine of “leave no trace” is always the guiding principle. But before that even comes into play, you need to familiarize yourself with local guidelines because best practices vary by location. Some parks urge visitors to walk in single file on trails to minimize the damage caused by a widened path. Other parks urge the opposite, with the idea that heavy traffic in a small track is worse than lighter traffic in a wider track.

The most responsible way to visit these natural areas is to prepare in advance to pack out everything that one packs in. Although watercolorists may be tempted to dump their brush water on the ground after an outdoor painting session, they should resist. “Yes, it’s water, but there are pigments in it,” Ekins points out. “Cadmium is a heavy metal, and it’s one of the big pollutants coming out of our mines here in Idaho. It will bind to the soil, and it doesn’t go away. If it did get into a water supply or stream, it could sit at the bottom of a lake for a long time. Use a small, sealable bucket to pack out any used paint water.

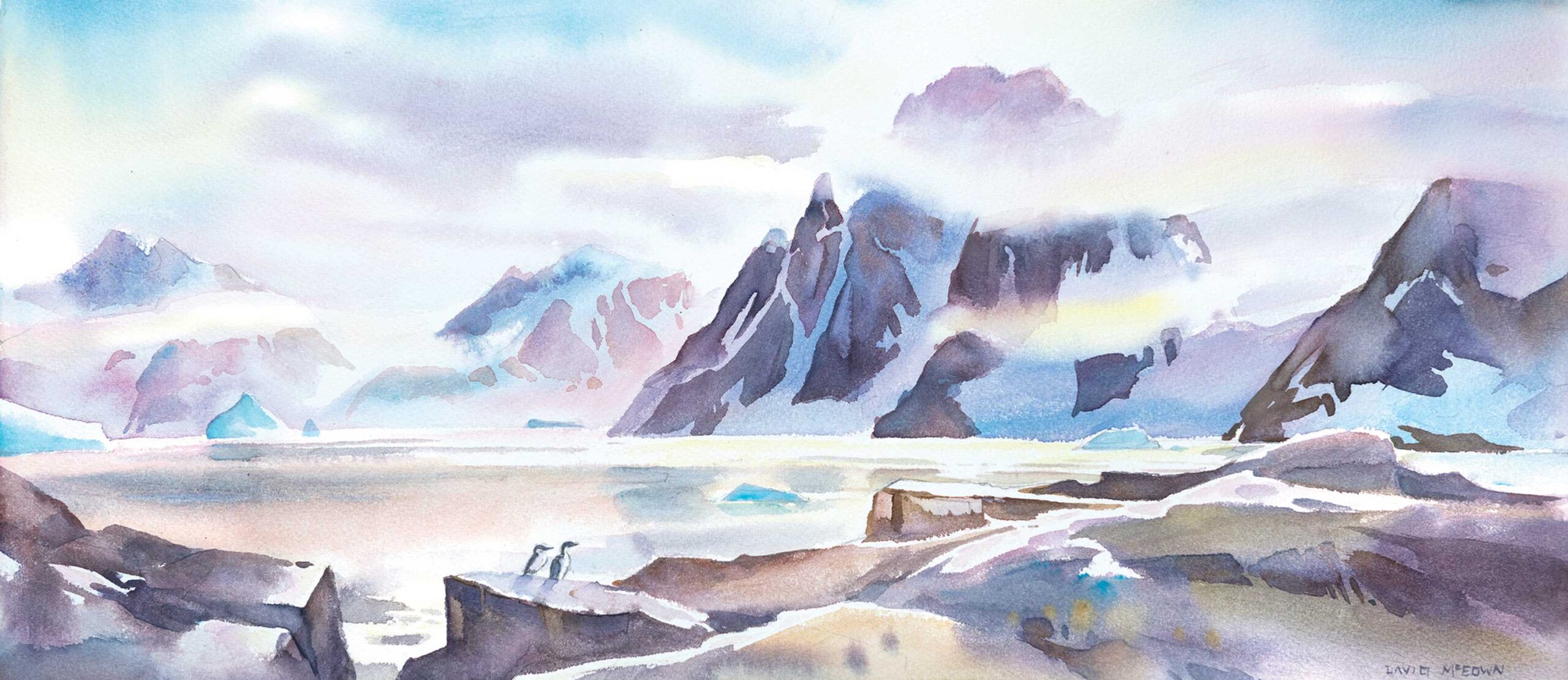

The stakes can be much higher for David McEown, who often paints at the literal ends of the Earth. Most of us won’t get to paint in Antarctica, but he has advice for artists who may find themselves visiting nearly untouched wilderness. “Before going to new parks and sensitive, protected areas, practice biosecurity,” he says. “This includes vacuuming all backpacks, camera bags, and pockets to eliminate the possibility of transferring invasive seeds or foreign matter. Clean Velcro straps and boot laces of clinging seeds. Also, do some boot washing and disinfecting of your tripod or easel and chair where they touch the ground. Do the same when returning to the studio.”

McEown continues, “Be mindful and never approach wildlife without proper guides, and do not set up on wildlife pathways. Animals have the right of way. It’s nice when they come by for a look at what you’re painting, but leave the area if wildlife — such as nesting birds — shows signs of distress. Try not to crush any vegetation, including mosses and lichens, and find rocks in open areas to set up on and leave a pack on.”

Use Common Sense When Painting on Location

Ekins touches on perhaps the biggest thing responsible plein air painters can do to minimize their impact on the landscape — be aware that others are watching you. As Bryant says, artists should remember that when it comes to humans, it’s often “monkey see, monkey do.”

“If they see a painter set up somewhere, it trains them to think that’s a place to do things, to picnic or something,” explains Bryant. “I know that people hiking will see me, and that is going to be a subconscious visual cue to what is acceptable. So I find durable surfaces upon which to set up. I don’t stop on plant-covered, stressed areas. I look for rocks. I take the trail that steps over to a large rock outcrop.

“If I’m not able to set up responsibly to capture a scene I’d like to paint, I take a photo. When in doubt, I err on the side of lightest impact. Large rocks are generally okay. But in alpine tundra especially, you don’t want to shift rocks. The rocks create shelter from high winds for little plants, and that creates coverage for larger plants. What’s more important? This one particular painting, or me being able to come back and see this landscape the same way it looked before?”

PleinAir Magazine provides expert insight and advice from today’s plein air masters, including step-by-step painting demonstrations and techniques for painting with any media outdoors; the latest news on the hottest online art events and in-person conferences; interesting historical perspectives on landscape art; and more!