Many people spend time each day on “mindfulness,” or achieving a state of peace by using techniques that eliminate stress and anxiety from their lives. Those techniques include meditation, deep breathing, and concentration, among others. The aim is to exist only in the moment and not to dwell on the past or future. Instead of worrying about things that might happen, or reliving difficult times in the past, the mindful person thinks about his or her current state of body and mind. For Canadian adventurer and artist David McEown, that state of mindfulness means living in a peaceful state of the present and maintaining a level of consciousness that is especially helpful for painting plein air watercolors.

There are many benefits to entering this state of mindfulness, including better health, but it can have immeasurable rewards for plein air painters, who need to become totally immersed in responding to nature. Those residuals are significant for watercolorists, who work with paints, brushes, and papers that are like gauges of an artist’s state of mind.

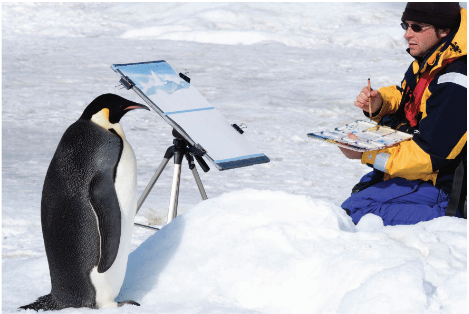

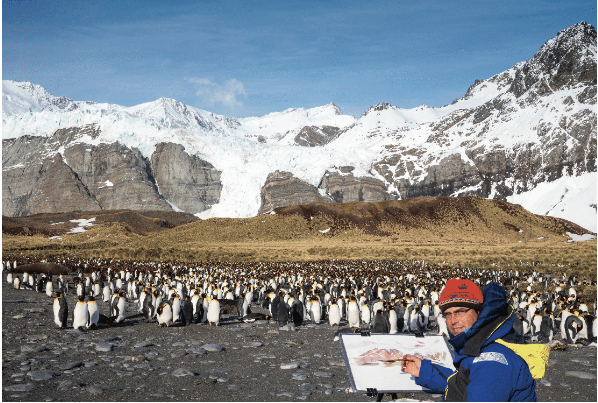

In particular, McEown needs to have total control over the flow of wet colors as they are pulled to the bottom of the 140-lb. watercolor paper he clamps to a board. That board is attached to a camera tripod that allows the artist to tip the paper in one direction or another as gravity pulls the moist colors down and across the paper. At the same time, he maintains a plan for preserving pieces of the white paper as the brightest, lightest value in the composition. In summary, McEown has to perform a high-wire act of balancing free-flowing colors and unpainted white shapes. That requires him to be in a mindful state and not distracted by any unrelated sights, sounds, thoughts, or emotions.

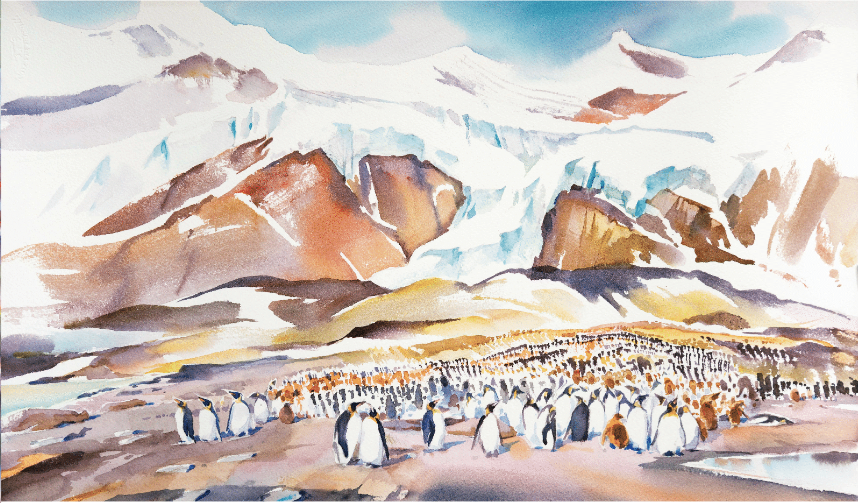

All of McEown’s supplies are chosen for their effectiveness, weight, and bulk because he often carries them for miles in a backpack as he hikes to remote locations. He paints on half-sheet pieces of Winsor & Newton or Arches bright white cold-press paper he carries to locations in a corrugated plastic folder. Once he has carefully considered the subject, he will paint, and the colors will be built up in layers of transparency. The artist makes a faint graphite drawing of the key shapes to establish a composition and a sense of pictorial space. Those lines are intended only as marks to guide McEown in making the first brushstrokes, with the balance of the shapes painted while the artist responds to the evolving image.

The watercolorist uses a limited palette of primary and secondary colors laid out in the pans of a handheld plastic Holbein folding palette that acts as a lid to a container and also holds his brushes and watercolor tubes. When he first painted in watercolors under the tutelage of Chinkok Tan, McEown used a selection of only three primaries. Over time, however, he added certain synthetic pigments that were appropriate for capturing the unique greens, blues, and yellows of glaciers, ice formations, and deep forests. “My choices change depending on where I will be painting,” McEown explains, “but I always aim to keep the selection, mixtures, and paint application as simple and direct as possible.”

Once McEown has reached his destination, he creates at least two paintings at that location, one under morning light and the other during the afternoon. “The scenes change fast, so I have to quickly nail down the overall pattern of light and dark,” says the artist. “As I work quickly, I have to remain sensitive to the way the temperature and humidity are affecting the drying time of the watercolors. In dry climates, I add lots of extra water to the color mixtures, and, if the atmosphere is damp, I reduce the amount of water and use something close to a dry brush technique. Another issue that can arise, especially in the polar regions that I often visit, is having watercolors freeze in subzero temperatures, so I sometimes travel with denatured alcohol, glycerin, or ox gall medium that can be mixed with the diluted paints to keep them from freezing. I should quickly point out that sometimes I want the paints to freeze and create random organic crystal patterns as the pigments freeze and thaw.”

The supplies McEown carries with him are also simple and efficient. In addition to the folder of papers and the plastic Holbein palette, the artist carries several brushes, including a No. 12 size Oriental brush, a 1-inch flat Kolinski sable brush, a 3-inch house painting brush, and a few calligraphy brushes. He also packs a paint scraper for pulling paint off a picture in places where he wants to add lines or textures, or to scrape out light shapes from dark washes. The heaviest item in his backpack is always the con-tainer of water that is essential for dissolving the paints and adjusting the way the paint accepts and releases brush marks. If needed, the artist will also pack basic camping gear and food for extended trips on foot.

DAVID McEOWN was featured in the August-September 2017 issue of PleinAir Magazine. He graduated from the Ontario College of Art and Design (Canada) in 1992 after off-campus pursuit of independent studies at the Algoma School of Landscape Arts in the remote wilderness of Northern Ontario. He was awarded the Elizabeth Greenshield Foundation Grant in 1994 and again in 1999, and he was elected a member of the Canadian Society of Painters in Watercolour, for which he served as a director from 2002 to 2007. His artwork has received national and international awards in various juried shows, with his most prestigious award being the A.J. Casson Medal from the Canadian Society of Painters in Watercolour.

I never thought of mindfulness in painting. But it’s true. When we paint, we’re in the “zone.” That really is mindfulness. And these paintings are fabulous!

Absolutely exquisite watercolors from these artists. To have skills of such excellence must be so satisfying to the artists themselves.