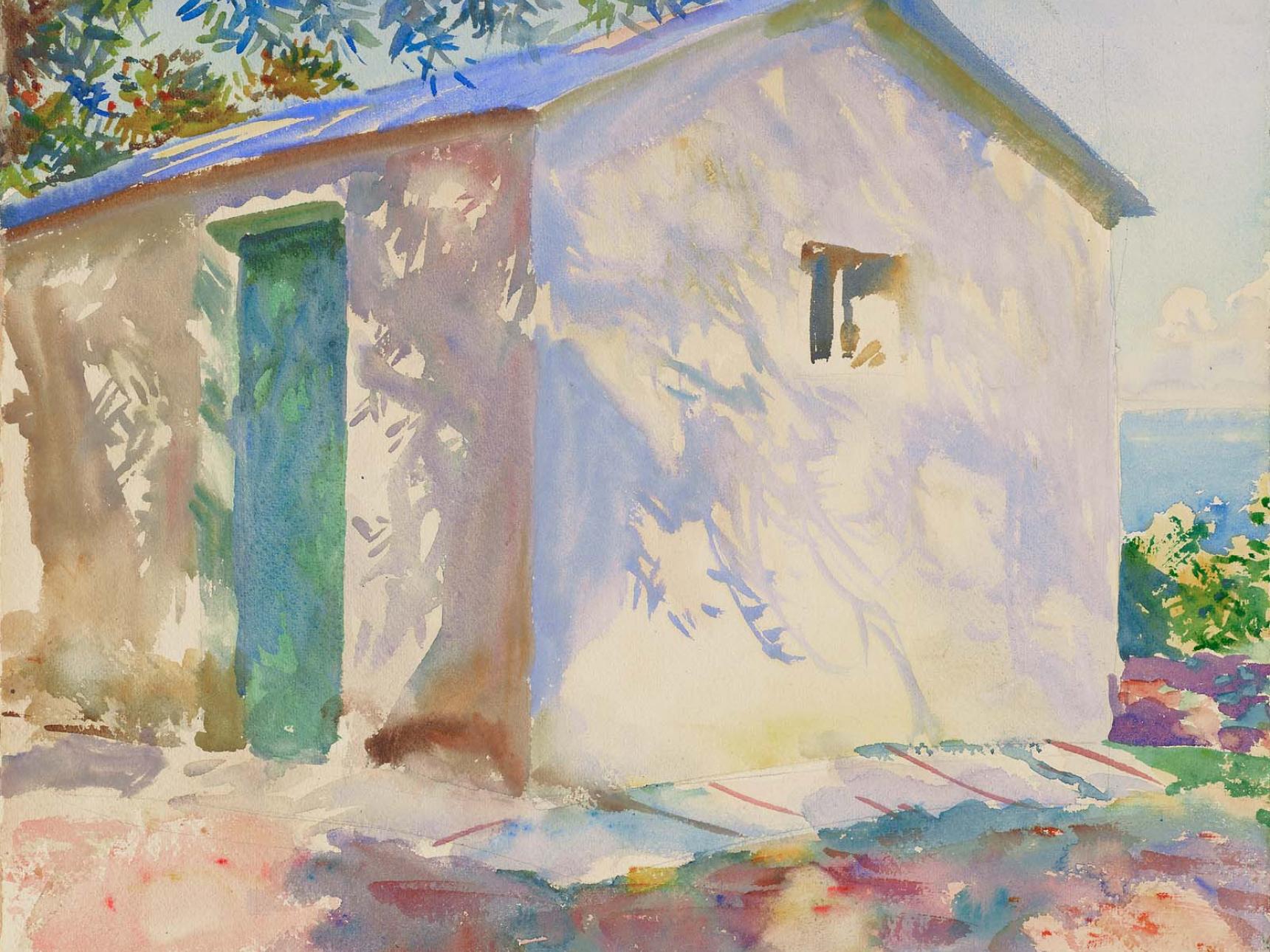

“To live with Sargent’s watercolours is to live with sunshine captured and held,” according to the painter’s first biographer.

Internationally recognized as the greatest American painter of his age, John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) took a bold and experimental approach to the medium that caused a sensation in Britain and the States. His daringly conceived compositions made in Spain and Portugal, Greece, Switzerland and the Alps, regions of Italy, Syria and Palestine demonstrate the unity of artist’s vision after the turn of the 20th century, when he aimed to free himself from the bother of portrait commissions and to devote himself instead to painting scenes of landscape, labor, and leisure.

In “The Bridge of Sighs,” Sargent saved the white of the paper to form the top of the arch; a hard line of blue pigment indicates where the wet paint of the sky met the dry, reserved paper. He created more subtle highlights by dry scraping, notably in the tan building beyond the arch and the waterline beneath. He also lifted wet paint, as can be seen around the prow of the gondola and in the sky to the right of the arch. He applied white impasto to the gondoliers and figures in the boat.

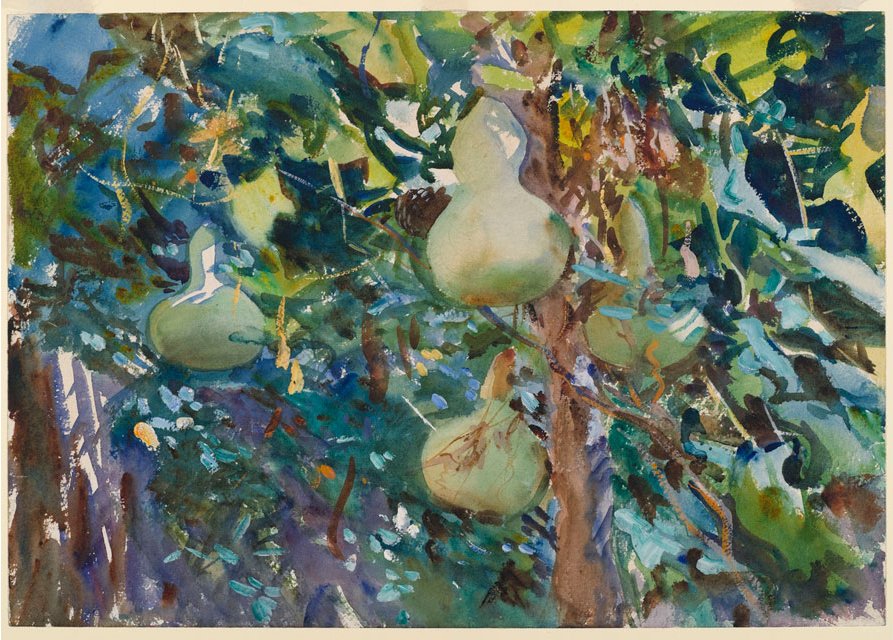

Sargent painted “Gourds” in Majorca in the summer or autumn of 1908, just months before the New York debut of his watercolors. In all of his garden watercolors, the artist relied on sculptural forms to anchor his portrayal of vivid light falling across leaves and flowers. Here, the fruits are made luminous with thin washes and exposed areas of paper, punctuating a maze of layered colors and whorls of dashed, opaque highlights.

Although “Mountain Fire” presents an expansive alpine view, Sargent’s attention to the enveloping effects of smoke and steam makes it one of his most abstracted watercolors. With this piece he clearly offered a farewell nod to the British watercolor tradition as exemplified by Joseph Mallord William Turner’s alpine subjects of a century before, in which deep perspectives were articulated with transparent washes. In contrast, Sargent evoked dense haze and smoke by adding opaque white to his washes and by freely allowing the bleeding edges of wet washes to suggest vaporous effects.

For more inspiring stories like this one, sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

As a novice at watercolors, I was unable to understand why Sargent is so revered by artists. Thank you for providing examples within your explanation: Now I get it.