“Watercolor has a false reputation promoting the idea that unlike oil paint, each stroke is impermanent and unfixable,” says Barbara Nechis. “Nothing could be further from the truth. Most errors can be easily scrubbed out and/or painted over when quality paper is used. Watercolor can also be intimidating because so much watercolor instruction focuses on difficult and unnecessary techniques. For example, most of us were taught by someone proficient in demonstrating how to produce a graded sky wash by leaving a bead of liquid at the base of each stroke and picking it up with the next stroke and moving down the paper. I still can’t do it but I can wet the paper, throw some paint on it, tip it to let it run, spray some more water on it if it doesn’t run enough and rinse it all off before it dries and try again as many times as necessary. I have never heard a child say ‘I want to work in oils because watercolor is too difficult.’”

What Watercolor Gives You as an Artist

“Watercolor does some of the work for you unlike many other mediums. It can give you unexpected effects that can’t be repeated so that each painting becomes unique. When it is done well and water used properly, watercolor can create an illusion that the paint arrived magically.”

Finding Inspiration

“I do not think about making a painting when I am observing shapes in nature. When driving or walking I am absorbing what I see. I photograph a great deal but I never use these photos. I think the process of framing an image helps to imprint the essence of it in my brain, although not the specifics. When I begin a painting I do not have an image of what it will be. I am not transferring thoughts to paper. My objective is to allow my feelings about a subject to come out naturally, then guide them into shapes and value patterns. Although the feeling of rock, trees, mountains, flowers or water is there because I have used their basic shapes, I haven’t actually painted these objects. Each painting is new and by allowing the water and paint to flow, letting the paper itself suggest the subject matter and the technique as well, ideas begin to arise. I invent images as I go along. I try to convey the essence of a subject not just describe its visual facts. I am watching each stroke as I put it down, adjusting it to fit with the previous stroke.”

The Artist’s Process

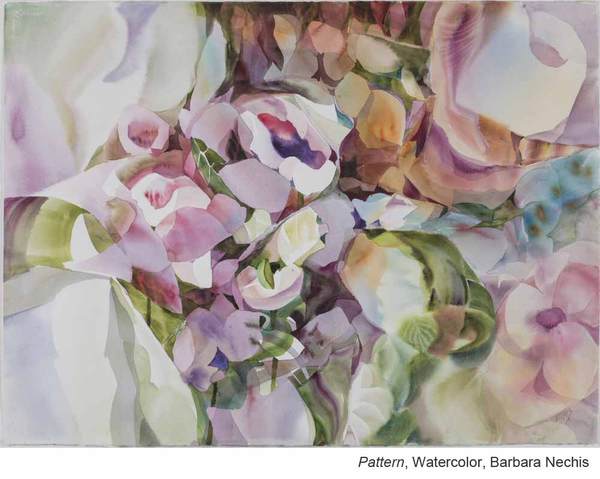

“My approach and subject matter differs from that of my teachers. I start with no vision at all. I begin without a specific image in mind and work through as one would work out a doodle which is never planned and where one thing leads to another. Sometimes I wet the whole paper and execute a wet-into-wet underpainting which will give subsequent layers depth and color variations. When I work on large paper I usually begin by making a large shape with as much water as the paper will hold, extending it to at least one edge of the paper. Then I pour off the excess water, add paint, dry it and then repeat with subsequent shapes layering over each other to create complex compositions. I am drawn to shapes in nature.”

Major Design Elements at Play

“For far too long I tried to follow design rules emphasized by my teachers. I have tried to forget most of them because most of the work I see in Museums makes the rules irrelevant. There is no center of interest in an enormous Monet water lily painting. Leonardo’s center of interest in The Last Supper is smack in the middle and Matisse, our color hero, rarely repeated colors for balance. Much of my approach to design is intuitive but most of my paintings have a predominant pattern of curvilinear or angular shapes that link from one to another. The questions I ask myself when I critique my own work are: Can the shapes be distinguished because values in adjoining shapes are varied? Have I chosen values to emphasize or diminish interest where appropriate? Have I filled the space? Are there areas of interest to stop and look at and keep the viewer interested? Do they flow together? Is there a connection between the parts of the painting? Does it have an unexpected element such as a color chord or intriguing shape? Have I already made a similar painting or is this one redundant?

“When you are painting, thinking too much about rules can interfere with the creative process. I think most who are interested in painting know more about design than they are aware of. When you look at a painting, usually if something doesn’t work it speaks to you. (Sometimes it yells at you.) The problem is how to fix it. I suggest before tackling it, find 3 solutions and discard the first one which usually involves scrubbing it out or throwing it away. Design comes from seeing and spending time with books of the art genre that interest you. Landscape artists need to study Sargent, Turner and Winslow Homer. Shape painters need to pay attention to Milton Avery.”

Barbara Nechis (Watercolor From Within and Tools for Transforming Troubled Watercolors) has developed a style known for its masterful balance of spontaneity and control of the watercolor brush.

Very interesting information. Some new, some a reminder, thank you!

And thank you Minnie

Thank you, Barbara Nechis, for your very interesting and informative thoughts. This was an article well worth the time spent reading, then looking, then re-reading, then looking some more….

Thanks Kate, I’m glad it is giving you food for thought

Thank you for this article – it’s what I’ve been thinking about all this time. Barbara Nechis: I love your artwork.

Thank you Juliette, I’m glad that we share similar thoughts.

I really like your art. It’s pretty but not specific.

Kelly

What an inspirational and educational article. Your comments about letting the paint do the work (paraphrased) are certainly extremely significant to me. I find as I’ve loosened up my approach to paint application and and creating a more impressionistic image that the potential to find a somewhat new direction in the painting being worked on is often the result. The results are much easier to achieve with watercolor than in any other medium that I’ve used in the past several years.