Thanks to her enchanting children’s storybooks, most notably The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter became one of the most successful author-illustrators of the 20th century. In such works, she defied expectations for women of her time by engaging in scientific studies, farming, and land conservation.

Organized by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum—home to the world’s largest collection of Potter’s artworks, “Drawn to Nature” features rarely seen objects, including personal letters, photographs, books, diaries, decorative arts, sketches, and watercolors that explore the inspiration behind Potter’s stories and characters.

Rupert Potter. Beatrix Potter aged 15 with the family’s spaniel, Spot, ca. 1881. Albumen print on paper; 8 x 1/2 in. V&A: Linder Bequest BP.1425. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, courtesy of Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

This unique exhibition, on display at The Frist Art Museum through September 17, 2023, reveals that her books emerged from her passion for nature and were just one of her major legacies. “From storyteller to natural scientist and conservationist, Beatrix Potter lived a truly remarkable and multifaceted life,” says Frist Art Museum senior curator Trinita Kennedy.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Born in 1866, Helen Beatrix Potter lived in the same London townhouse until she was 47 years old. She and her younger brother kept dozens of pets, including rabbits named Benjamin and Peter, bats, birds, lizards, mice, snakes, a dog named Spot, and a hedgehog named Mrs. Tiggy, which would inspire Potter’s art and storytelling. “Potter was educated at home by governesses and was encouraged to draw, paint, and study natural history through books, museum visits, and direct observation,” writes Kennedy. “She collected fossils, insects, plants, and rocks, and used a microscope to make hundreds of detailed drawings of her specimens. Around the age of twenty, Potter developed a special interest in mycology, the study of fungi. She might have pursued a career as a professional scientist, had more pathways been open to women in the 19th century.”

Before her literary career began, Potter created and sold greeting cards, the first of which featured her own pet rabbit, Benjamin. She was also in the practice of writing entertaining letters to children that were embellished with drawings, and in her mid-30s, she turned some of her letters into books. By the time she found a suitable publisher for her stories, Frederick Warne & Co. (today an imprint of Penguin Random House), in 1902, Potter had enough ideas that she released approximately two books a year until 1913. “She took great interest in all aspects of the design of her books, including the cover art, typefaces, end pages, and format,” writes Kennedy. “She was even particular about their size. Always attuned to her audience, she wanted small books for little hands.”

The Tale of Peter Rabbit has never been out of print since it was first published and has sold more than 46 million copies globally. Today, more than two million of her “little books” are sold every year, while Peter Rabbit has appeared on books and merchandise in more than 110 countries.

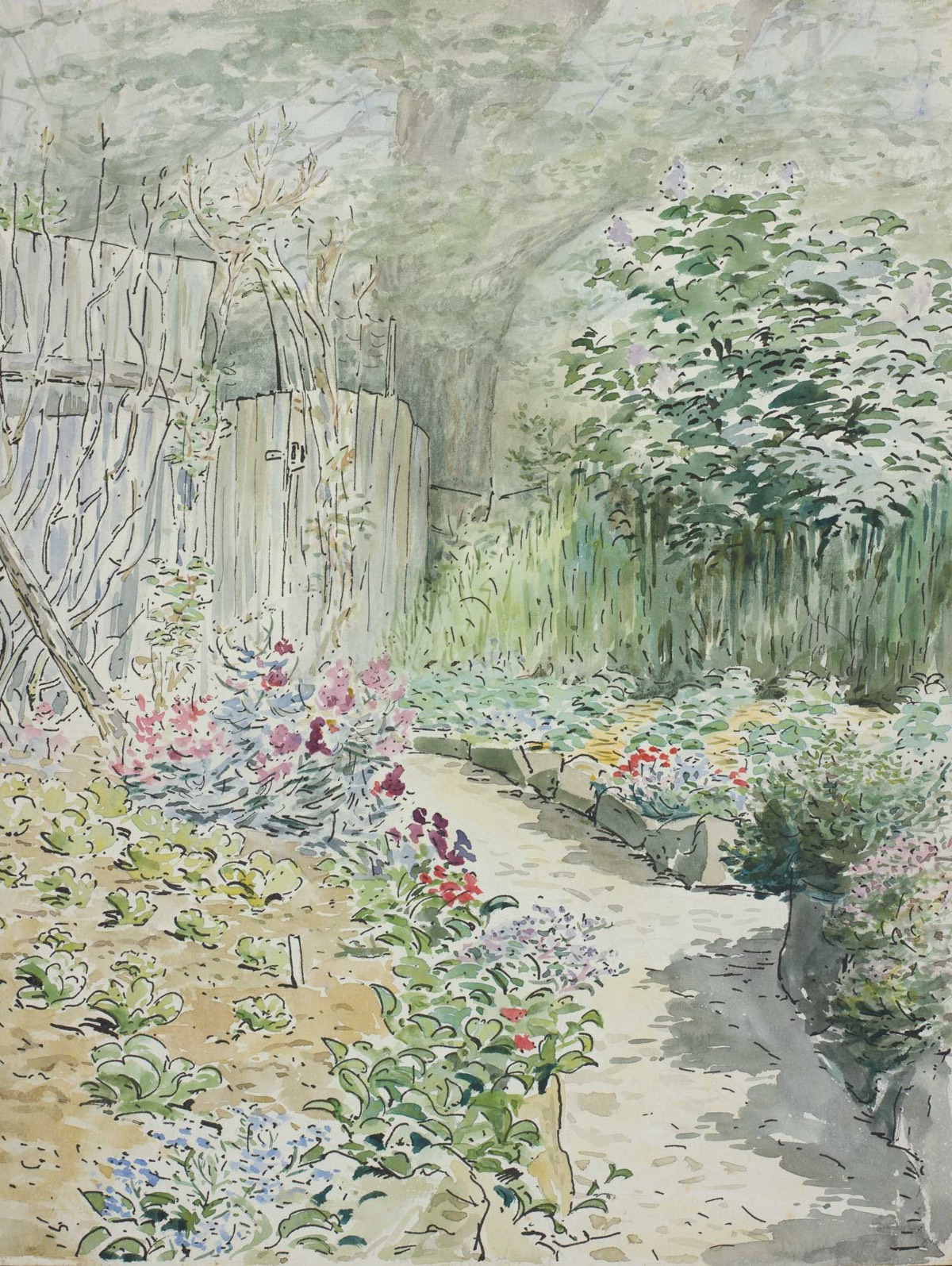

Using royalties from her first books, she purchased the 34-acre Hill Top Farm in the Lake District of northern England in 1905. The property includes a 17th-century house, an orchard, and a garden Potter nurtured. The Lake District serves as the setting for The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, The Tale of Tom Kitten, and The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy Winkle.

As part of her efforts to preserve the natural beauty and agricultural way of life in the Lake District, Potter acquired more property there. Between 1913 and 1930, she published only four books and turned her attention to rural pursuits. When she died at age 77 in 1943, she left Britain’s National Trust over four thousand acres and fourteen working farms—the largest bequest the charity had ever received. Today, her farms remain in operation, and Herdwick sheep, an ancient breed she helped to thrive, still graze in the hills and valleys of the Lake District.

“We hope this exhibition will inspire natural scientists, conservationists, and farmers as well as artists and storytellers,” says Annemarie Bilclough, Frederick Warne Curator of Illustration at the V&A. “Potter’s story shows that through talent, passion, and perseverance, life can take unexpected twists and turns and great things can grow from inconsequential beginnings.”

Celebrate the power and endurance of watercolor at next year’s Watercolor Live!