By Daniel Grant

Perhaps it’s no surprise that Anne Hightower-Patterson’s early influences were painters who looked long and hard at other humans, such as Andrew Wyeth, Winslow Homer, and John Singer Sargent. In their work there seems to be a story, though we are not always certain what it is.

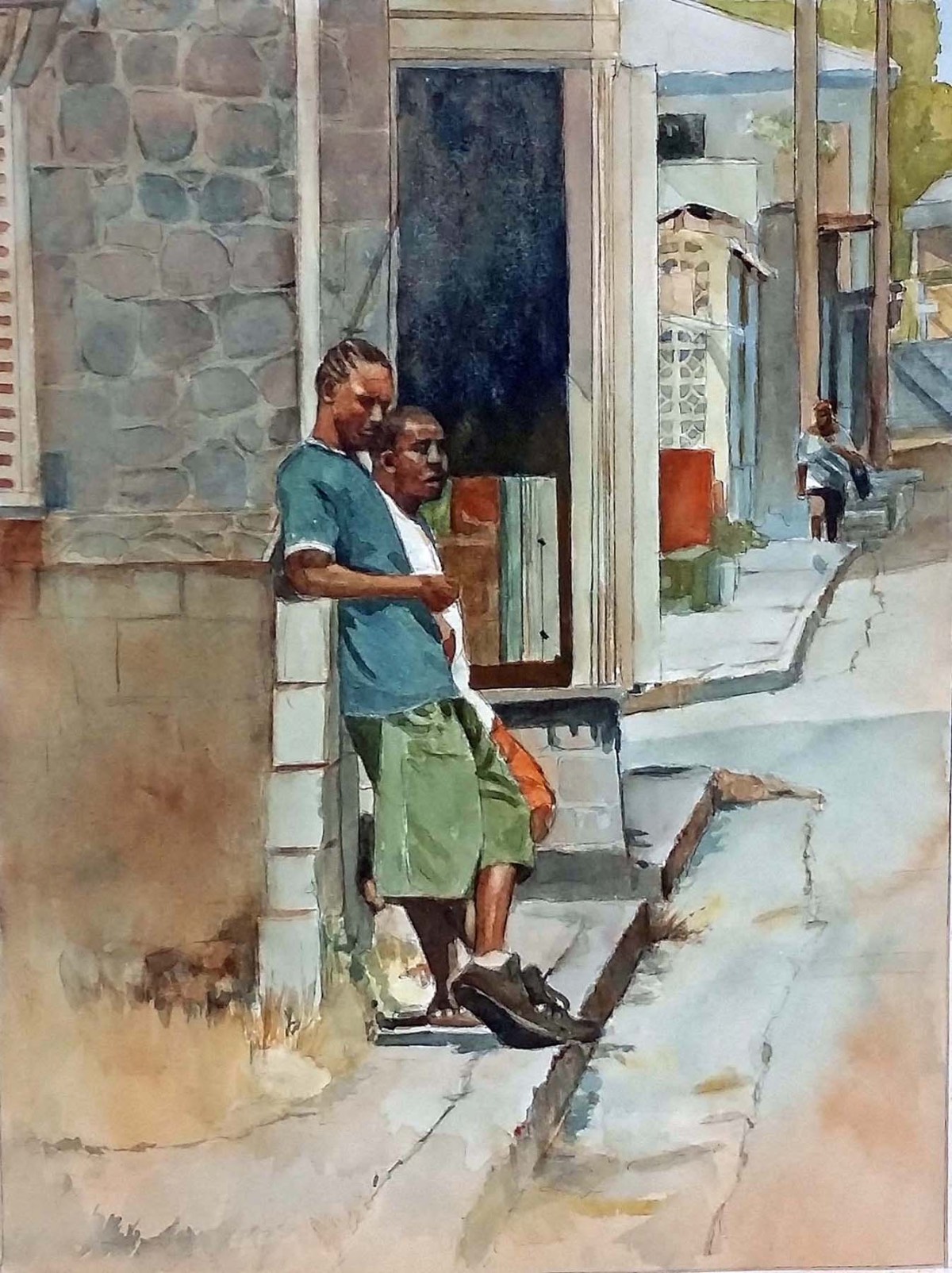

Like Wyeth, Hightower-Patterson reveals an interest in a lived life, exemplified by her subjects’ faces and bodies and contextualized by their surroundings. They are physical objects on which a strong, often high-noon, light produces contrasts of shadow and glare, but they also are human beings to whom she directs our attention. “Light is everything in watercolor,” the artist explains, “but ultimately my work is about the story or the place, how I’m struck by that.”

What first interested her about the man wearing a do-rag and earphones depicted in Won’t You Be My Neighbor “were the shapes and the color and the light,” but she drew the painting’s title from Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood as “a statement about judging people based on how they look and not who they are.” She says, “People are funny. They carry their prejudices under their sleeves.” Hightower-Patterson was inspired to paint Won’t You Be My Neighbor in the aftermath of the 2015 massacre at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, which took the lives of nine African-Americans during bible study.

For some artists, people are objects to be painted, and capturing skin tones and the effects of light and shadow are their stock in trade. Seeing beyond the surface to the struggles that a person may have faced and the story behind those struggles is one task of art, which Hightower-Patterson seeks to capture through the title, if not the image itself.

Those are a woman’s hands in Hands of the Homeless, and this lady has appeared in several of Hightower-Patterson’s paintings. They met when the artist was in a city park and the woman asked her for five dollars. “I looked at her and said, ‘I’m not going to give you any money, but if you’ll pose for me, I’ll give you $5.’ And so she very happily sat down, and I took a bunch of photographs. Well, we had lots of conversation, and all of a sudden, I saw her not as a panhandler, but as a person. And she told me how she ended up homeless and how she wanted to get her kids back and how she hoped to get a job. And we talked about an hour, I gave her $10, and I drove her somewhere she wanted to go.” (As a postscript, the two met again some time later. The woman had seen in a magazine one of the paintings Hightower-Patterson had made and said she was now working in a hotel. Still, she asked the artist if she had any change. “I emptied all my change out and gave it to her. And that’s the last I’ve seen of her.”)

A FOCUS ON DESIGN

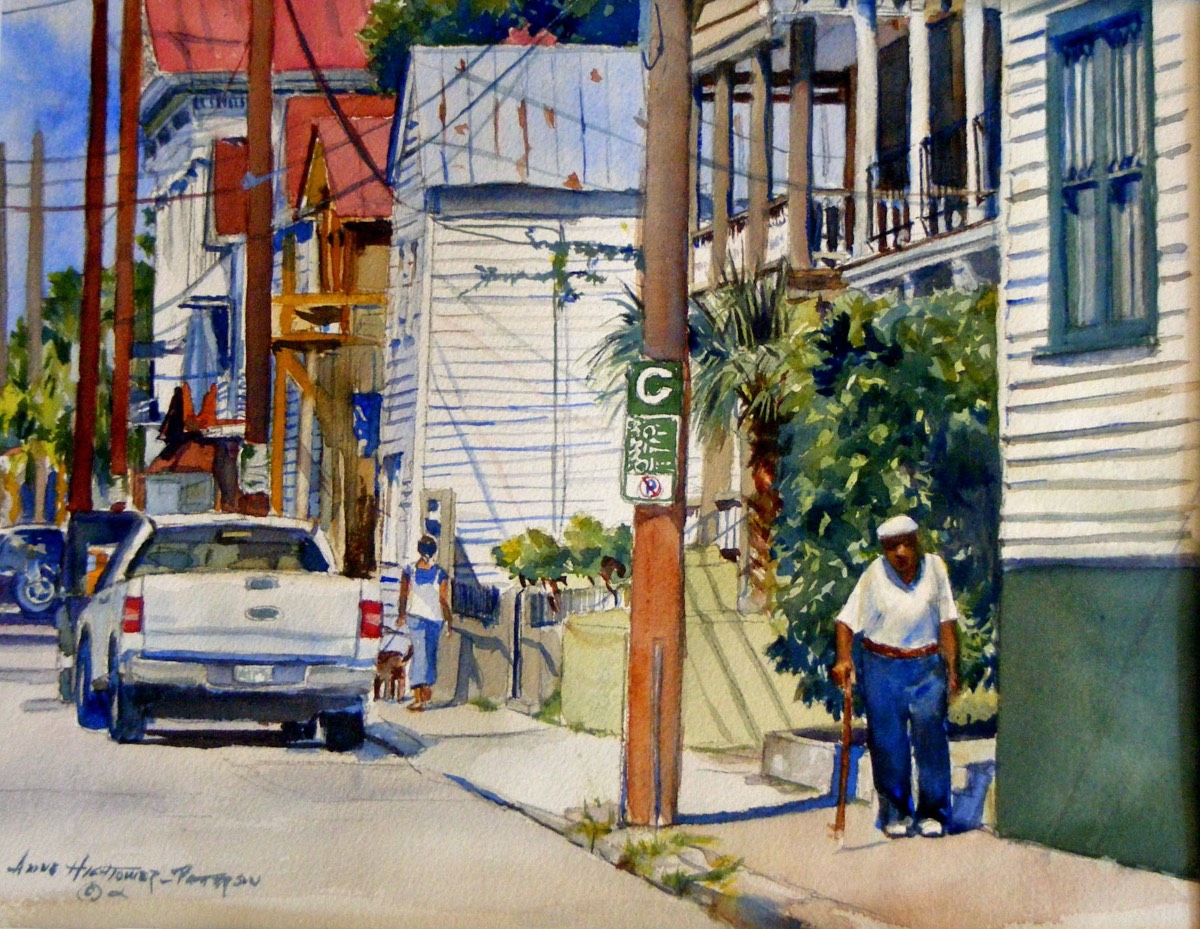

“There are two things in art you have to learn,” says Hightower-Patterson. “First, the compositional elements like line, shape, value, and texture. And second, how to put it all together.” Hightower-Patterson’s focus on design is evident in Spring Street, which ostensibly shows a somewhat run-down city street along which an elderly man walks; further down the sidewalk, a woman walks her dog. Notable here is the geometry of vertical telephone poles and architectural columns, horizontal clapboards, and diagonal telephone lines and shadows.

“Good composition is always based on horizontals versus verticals,” the artist explains. “That becomes the armature upon which I build my compositions; those elements move the eye through the artwork.” Still, it is the sense of place (“an area of downtown Charleston not yet gentrified”) and the people who live there that give Spring Street its pathos.

When she isn’t painting people, Hightower-Patterson depicts still lifes, flowers, and outdoor scenes such as city streets or waterways with wildlife or boats. When we see such works as Morning Snaps or Fiesta in Glass, with their prisms, reflections, and juxtaposition of objects and textures, we might think, “This artist is showing off.” And, to a degree, she is. “It is partly to show that glass and that shiny object in light, because people are always fascinated and don’t know how you do it,” the artist observes. “So it’s kind of fun to leave them in wonder.”

Hightower-Patterson quickly relates these subjects to an important forerunner, Carolyn Brady (1937–2005), who specialized in hyper-realistic watercolors of flowers and table settings. Another watercolorist who has made an impact is Carrie Waller (b. 1976), best known for depicting empty and filled Coke bottles, Mason jars, and light bulbs that reflect and refract bright light. The two artists have never met, but they communicate through Facebook.

Because of its loose, spontaneous nature, watercolor has a reputation for not being an appropriate medium for painting figures or portraits. Mario Robinson turns that notion on its head with his unique approach to painting figures in watercolor — perfect even for beginner painters.