“Inspiration is probably the most important factor in creating a wonderful painting,” says Catherine Hillis. “Sometimes inspiration alone, though, is not enough to paint well, especially if there’s unfamiliar subject matter that requires learning new technical skills. Two years ago I moved from the Mid-Atlantic region to the southeastern coast of Georgia, and my subject matter changed dramatically. I was presented with the opportunity to learn how to paint new things: marshes, Live Oaks covered in Spanish Moss, palm trees and seascapes. I’m always struck by the marshes: the tidal changes in Coastal Georgia are dramatic, and can range over 8 feet. I’m learning how to convey the drama and beauty of the marsh. I hope these step by step ideas are helpful. Of course, they are only suggestions because there are many ways to approach these subjects.”

Marshes

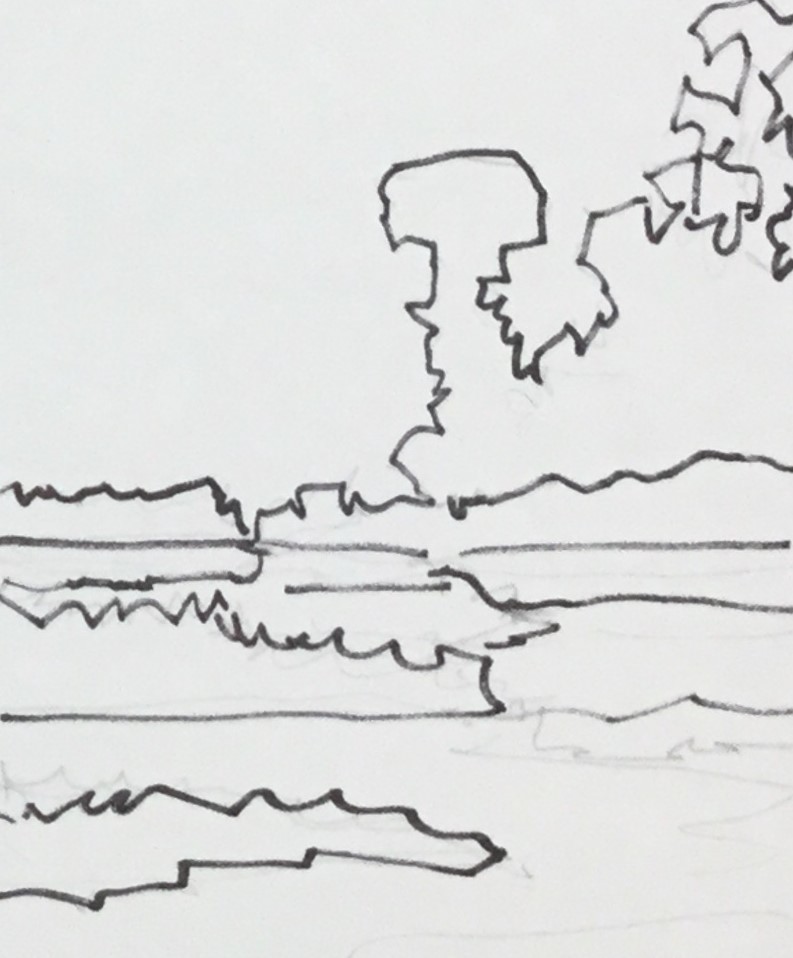

“It’s easy to want to paint detailed grasses in marshes, but I try not to. My painting is about the marsh, so I try to approach the painting as I do any landscape: a geometric plane with background, mid-ground, and foreground. I look for simple shapes within the marsh scene, and pay attention to how those shapes connect; I try to forget the details at this stage.”

“I take photographs of the scene I want to paint or if I’m in the field, as in this case, I squint. I then study the scene so I can understand the simple shapes involved. In order to understand the shapes, I make a simple contour drawing. Once I have a good contour drawing, I can then transfer a drawing to watercolor paper. If I’m working en plein air, I squint to see the simple shapes before me and proceed from there. I use 140-lb. rough paper and mop-style brushes, along with granulating paint for most landscapes.

“From my contour drawing, I see the marsh contains a background, a mid-ground, and a foreground. The color temperature and the values of those three distinct areas are very important. It will be critical to create depth in the marshy landscape by using cooler colors and lighter values in the background, while the foreground will need to appear to come forward; otherwise, the painting will appear flat and without dimension.”

“I save my thicker paint, warmer colors, and details for the mid-ground or the foreground, depending upon where my focal point is. Putting in the water reflections wet-on-wet pulls the painting together. Finally, I painted individual grasses and details with a smaller brush or a rigger in the foreground, which is closer to the viewer.

Live Oaks and Spanish Moss

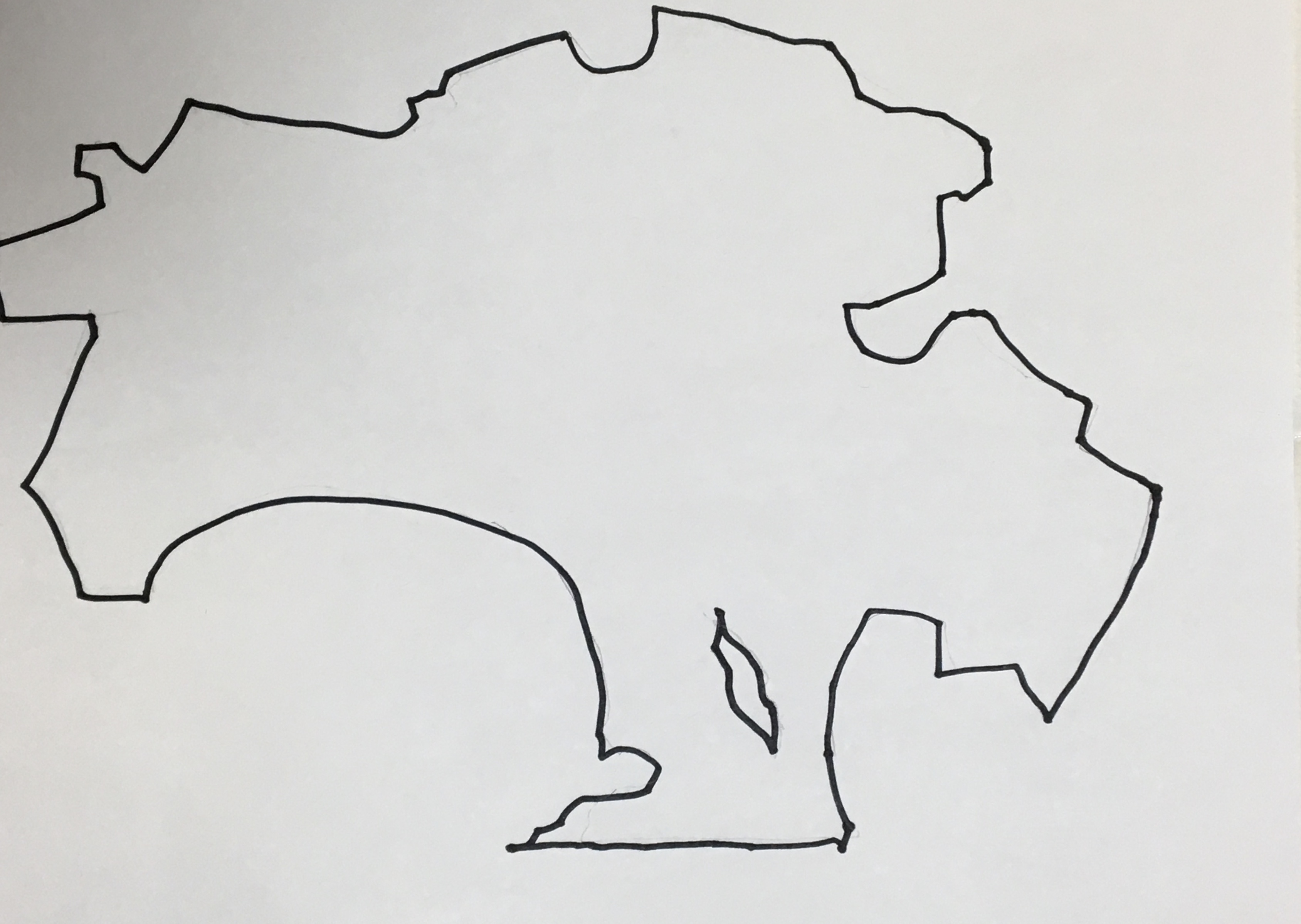

“Spanish Moss is an important and beautiful part of the landscape that represents the South. It’s much more complex when you begin to study it: it’s highly textured with lots of spaces of light showing through, plus it absorbs and reflects light. There are many values in a clump of moss, ranging from dark to light, and there are both warm and cool color temperatures bouncing among the clumps. Of all the topics in my new home, I find Spanish Moss the most difficult one to paint.

“I’ve spent hours studying how other watercolorists paint moss. I’ve tried all sorts of approaches: pen and ink, delicate fine lines, different colors. I’ve discovered that if I paint too much detail in the moss, that area becomes a focal point and I lose the delicacy and curvilinear shapes needed to convey the topic.

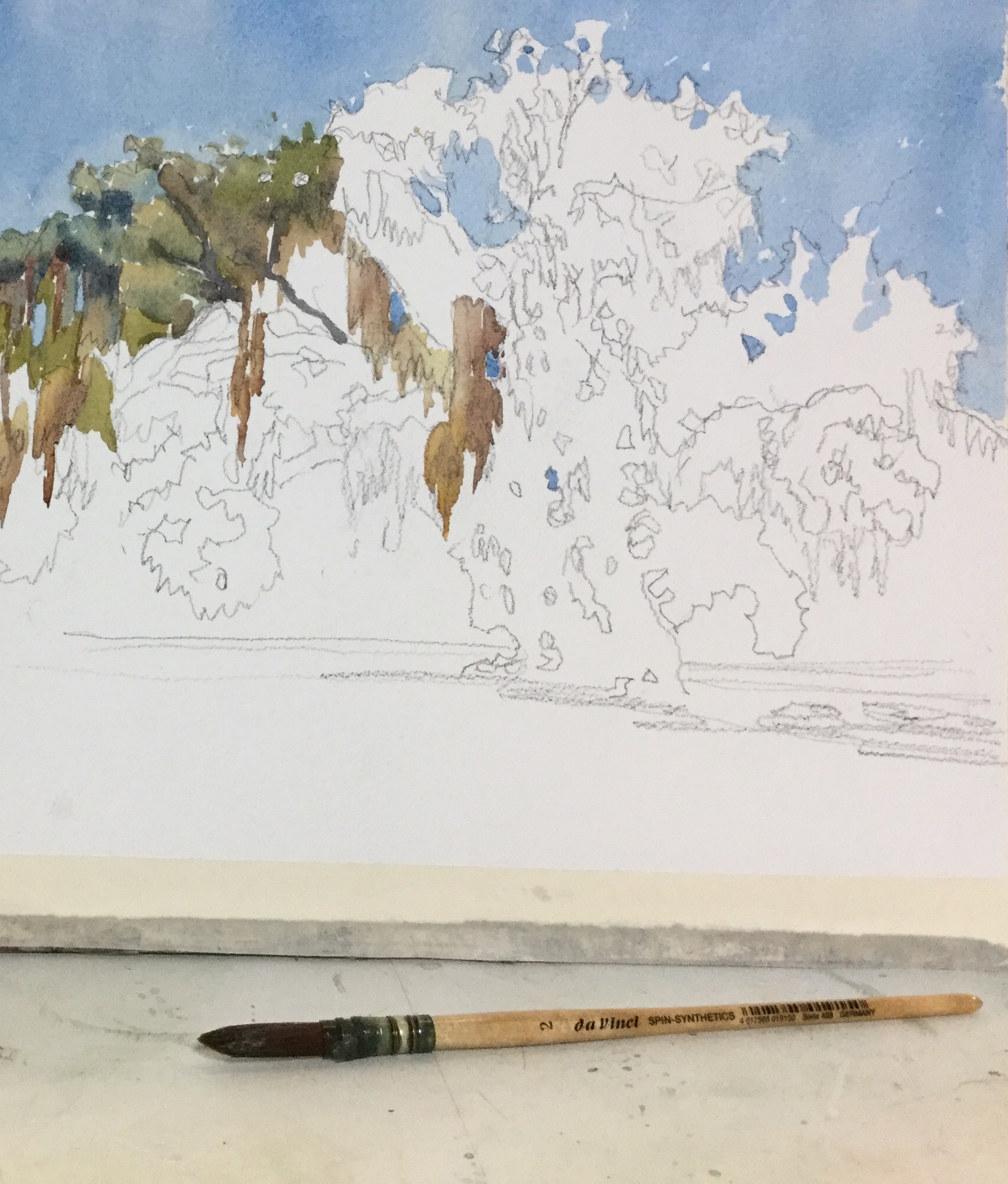

“I find the most credible manner for me to replicate Spanish Moss is to keep it simple, draw the contour lines of moss clumps and paint the graceful shapes alone, wet on wet, using granular paints that will do most of the texturing work for me. I try to focus on value and temperature only when painting moss, conveying no detail at all.”

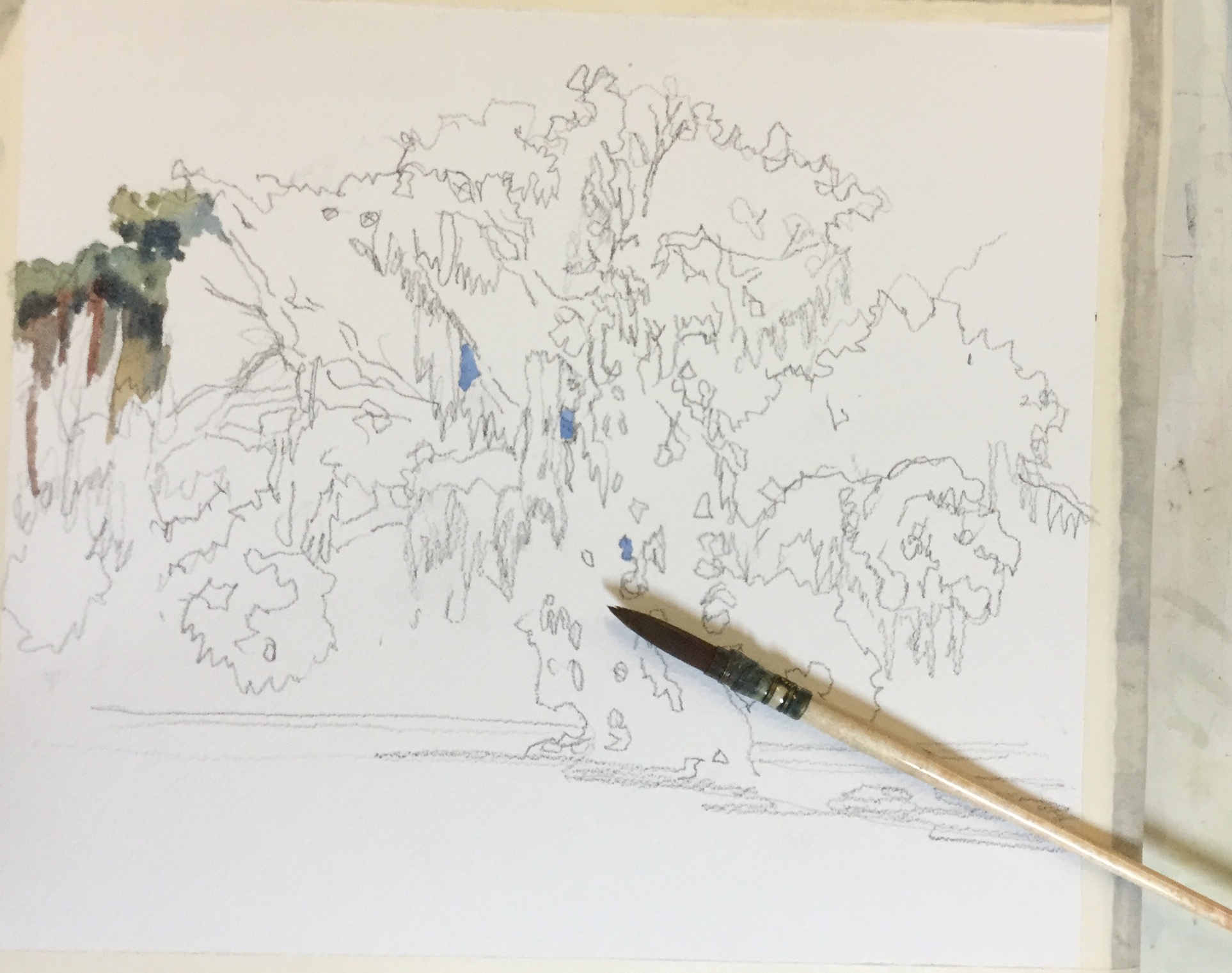

“Cerulean Blue, Manganese Violet, Ultramarine Blue, and Cobalt Blue are my preferred cool colors. I’m experimenting with granulating warm colors from Daniel Smith Company that include Burgundy Yellow Ochre, Fired Gold Ochre, Hematite Genuine and Goethite Brown Ochre. I like using these paints for their texture, but it’s important to paint to the right value the first time so I don’t lose the granulating features and the refraction of light from the granules. I might also use Raw Umber and Burnt Sienna.”

“I begin painting the clumps of leaves first. Paint colors might include cobalt blue, ultramarine blue, Burgundy Yellow Ochre, and Serpentine Green. I mix both warm greens and cool greens. I will move back and forth between painting leaf clumps with cool and warm colors and then I paint graceful clumps of moss using Burgundy Yellow Ochre, Goethite Brown Ochre, Hematite Genuine and Cerulean Blue — all granulating paint. I might drag a finger along the bottom of clumps to drag the paint down for a drybrush effect and I use gravity, too, holding the paper upright and letting the paint droplets flow down.”

“I focus on getting the simple shapes right and painting warm and cool colors into the wet on wet areas. I try to get the value right with my first stroke. The colors for the trunk are Hematite Genuine, Neutral Tint, Ultramarine Blue, Goethite Brown Ochre and any other warm or cool colors I might need. I often mix green in the trunk since the leaves and the grass are reflecting on that shape.”

“When I paint marshes and Live Oaks, I use 140-lb. rough paper and looser mop brushes to achieve looser strokes. I enjoy painting with granulating paint for the surprising texture it adds to my work and I like to minimize detail and focus on the large shapes first. I create a contour drawing in order to simplify the shapes and try to eliminate as many details as I can in the beginning of my work. It’s best to let the paint, paper and brushwork do their job. Careful planning will usually lead to success. My paintings of the Southern landscape are a work in progress that will change and develop with time.”

Catherine Hillis’ article and illustration was excellent!! I am an oil painter and just beginning with watercolor. Have never even heard of granulating paint but I have now! Catherine is such a great painter!

I use a lot of the granulating paints by Daniel Smith and Co. They are so rich and a joy to use. Give them a try because I think you’ll like them. Happy painting. Catherine Hillis, catherinehillis.com

Catherine Hillis is a talented and professional artist with much to teach. I have learned much in her classes. My home has several of her beautiful art works which remind me to pick up the brush. Thanks for this detailed and helpful article.

Thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed the article and try to paint Live Oaks. They’re a challenge. Happy painting. Catherine Hillis http://www.catherinehillis.com

Love your work!

Thank you, Lois. I appreciate your comment. I paint every day and am grateful to be an artist.

Many good regards, Catherine Hillis

As usual an impeccable explanation of how to approach these subjects. It feels like you are in her class and painting along. Thanks Catherine.

Thanks

Megha, I thank you for your comment. I love to teach! Catherine Hillis catherinehillis.com

Thanks for the detailed explanation accompanied by diagrams with various steps. We need to keep hearing the basics–focusing on large shapes and less detail.

This is one of the best demonstrations that I have seen. Having lived in

the south for many years, I love to paint Oak trees but never create them as well as I wish. Thank you for this demo!!!