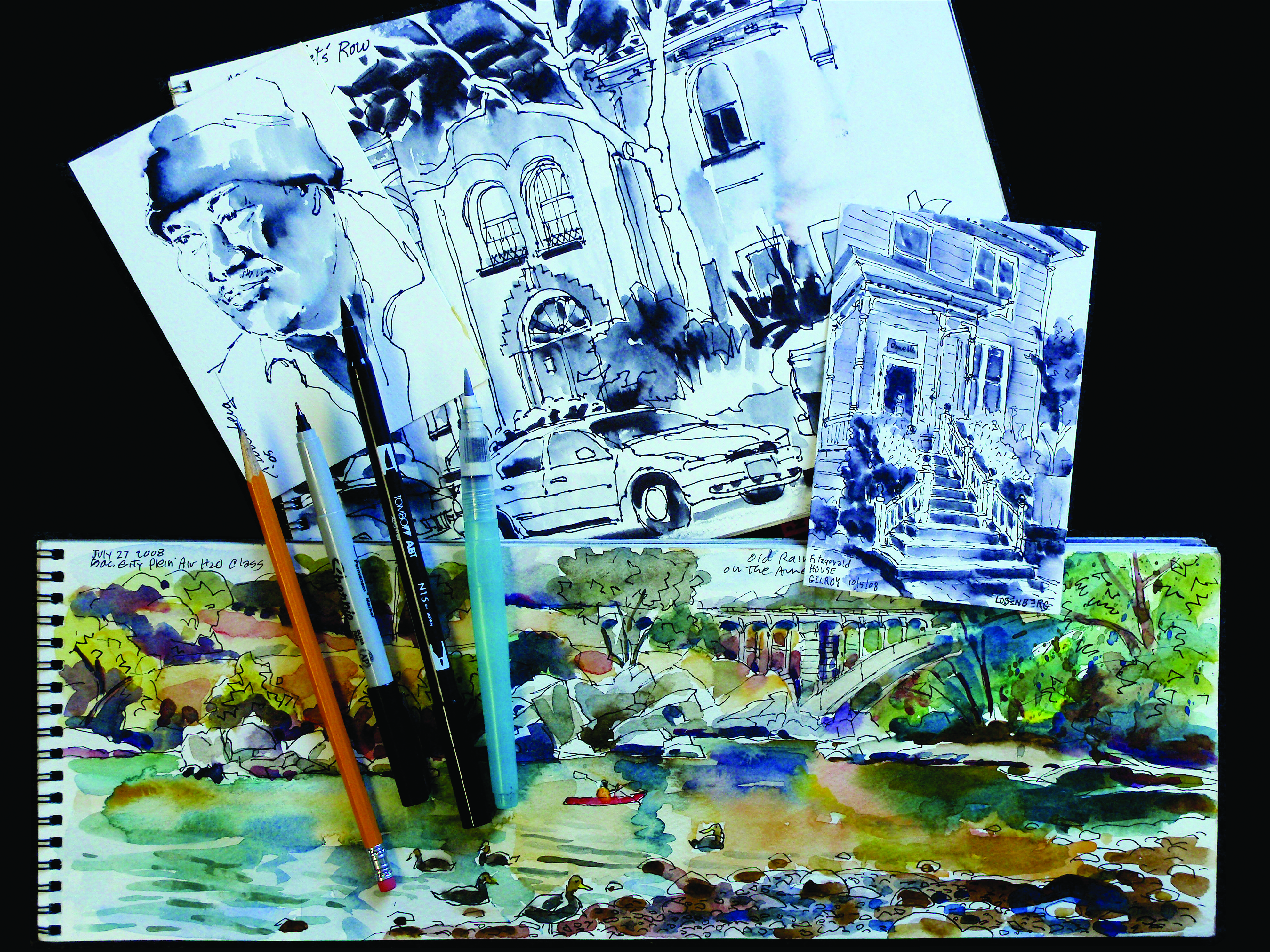

When Californian David Lobenberg prepares to paint outdoors, he is more apt to be loading his art supplies into Ziploc bags than a canvas backpack. That’s because his intention is to create fill a dozen pages in his spiral sketchpad with ink sketches or paint several quarter-sheet watercolor paintings during the time available.

“It’s amazing how much we can remember after spending just 10 or 15 minutes sketching people in a cafe, the sun disappearing below the horizon, or clouds rolling across a landscape,” Lobenberg says. “In the time it would take me to set up an easel, lay out a palette of colors, and block in a plein air painting, I can complete two or three sketches of fleeting scenes. The key is to have supplies at the ready and to know how each pen, pencil, and brush can be used.”

Among Lobenberg’s favorite sketching tools is a Tombow Dual Brush pen that has a fine-pointed, hard nylon tip on one end and a flexible brush tip on the other. The pens can be purchased individually or in sets of either six or 10 landscape colors (light sand, burnt sienna, redwood, gray-green, true blue, hunter green, lamp black, navy blue, and warm gray 5). The ink is water-soluble so the pens can be dipped in water to create subtle color washes or the drawn lines and dabs can be dissolved with a brushload of water to create various value washes.

“The Tombow brushes are also available in shades of gray, and those are great for making quick value studies before starting a watercolor or acrylic painting on location,” sats Lobenberg. “I’ve done compositional value studies with a Tombow brush as well as a Niji Waterbrush. The Niji brush has a reservoir that I fill with tap water. I then lay down small or larger dabs of Tombow ink on a sketch and simply use the Niji brush to dissolve them into value washes. The Waterbrush is available in broad and pointed nibs, and I’ve also made use of an ultra-thin Sharpie pen when I want to draw with a permanent ink rather than with watercolor.”

Although Lobenberg is enthusiastic about water-soluble graphite pencils, he finds that most water-soluble colored pencils become too faint when the lines are dissolved with water. However, he does like using the Caran d’Ache Pablo colored pencils,or the Caran d’Arche Supracolor soft aquarelle pencils for drawing in color and creating washes by dissolving the pigment.

“I use these drawing tools in much the same way I would a brush,” the artist explains. “That is, I squint to first see the values and shapes in a subject, and then I open my eyes to see the edges. Kevin Macpherson coined the term ‘val-hues,’ and that’s the perfect word to identify the important color value relationships. I can quickly sketch those in with staccato, broken lines, dissolve the lines with water or overpaint with transparent watercolor, and then add details with either an ink pen or a water-soluble pencil.”

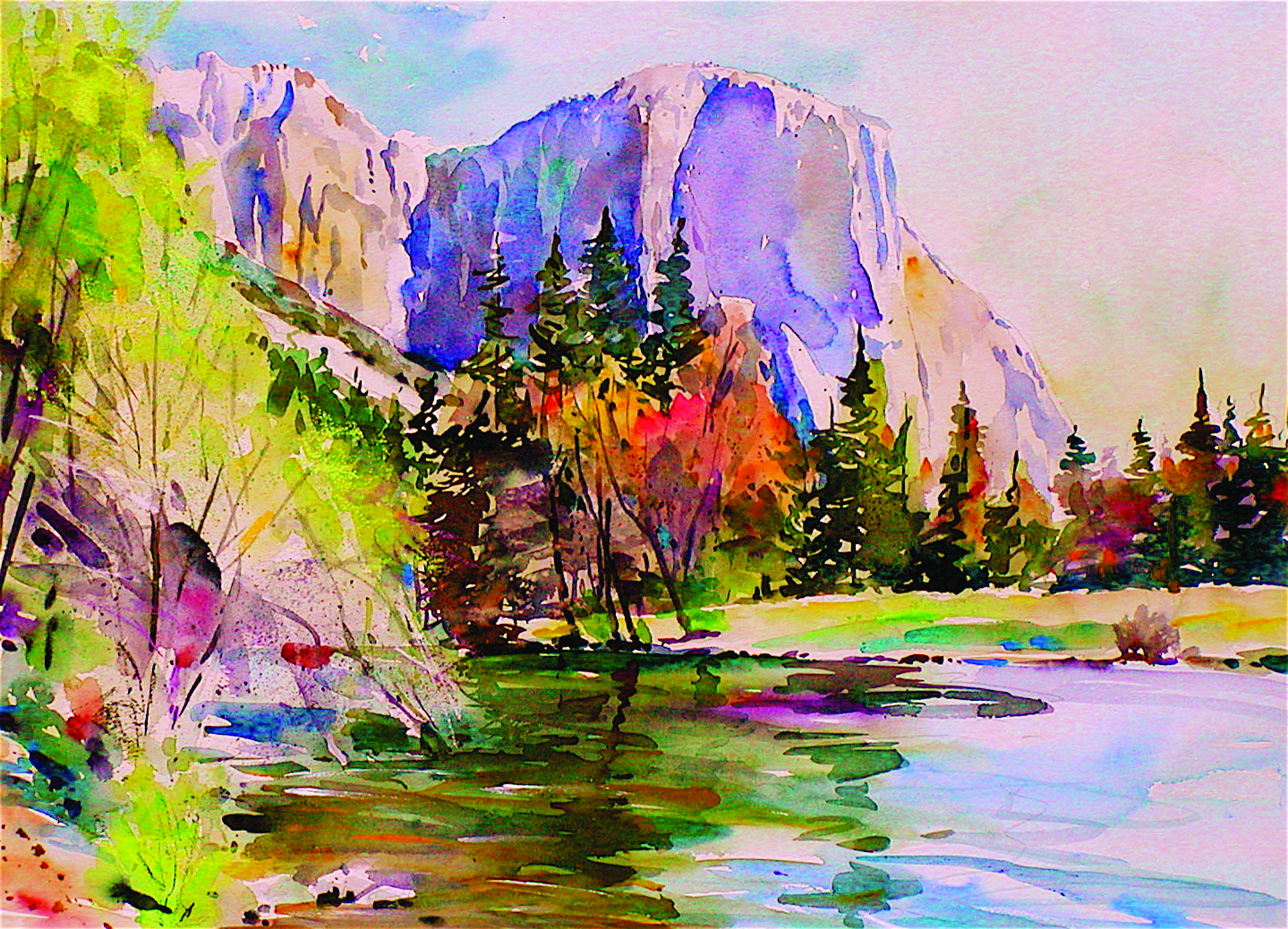

When Lobenberg wants to sketch with just watercolors, he uses a synthetic hair brush and paints made by Winsor & Newton, Schmincke, Daniel Smith, or Mijello Mission Gold watercolors; he says, “I only recently discovered the Mijello Mission Gold paints, and I like their intensity.” His normal palette of colors includes cadmium red, alizarin crimson, cadmium yellow light, cadmium yellow medium, bismuth yellow, raw sienna, burnt sienna, yellow ochre, burnt umber, cobalt blue, French ultramarine blue, cerulean blue (especially when painting portraits), phthalo blue, and Payne’s gray. He doesn’t use tube greens because he prefers to mix all his greens.

Lobenberg prefers to sketch in spiral-bound sketch pads consisting of sheets of 140 lb. cold-pressed watercolor paper because pens and brushes move quickly across the hard surface, the paper is heavy enough to accept washes without permanently buckling, and the spiral binding keeps the sketches together. If he wants to use transparent watercolor for more painterly sketches, he does those on sheets of either Fabriano or Arches natural or bright white cold-pressed or rough paper. “I don’t like painting on watercolor blocks because I have to wait for the top sheets to dry before I can use the pages below,” he says. “I like to cut up sheets of cold-pressed or rough watercolor paper into sizes as small as postcards that I can store inside the plastic sleeves of an inexpensive photo album.”

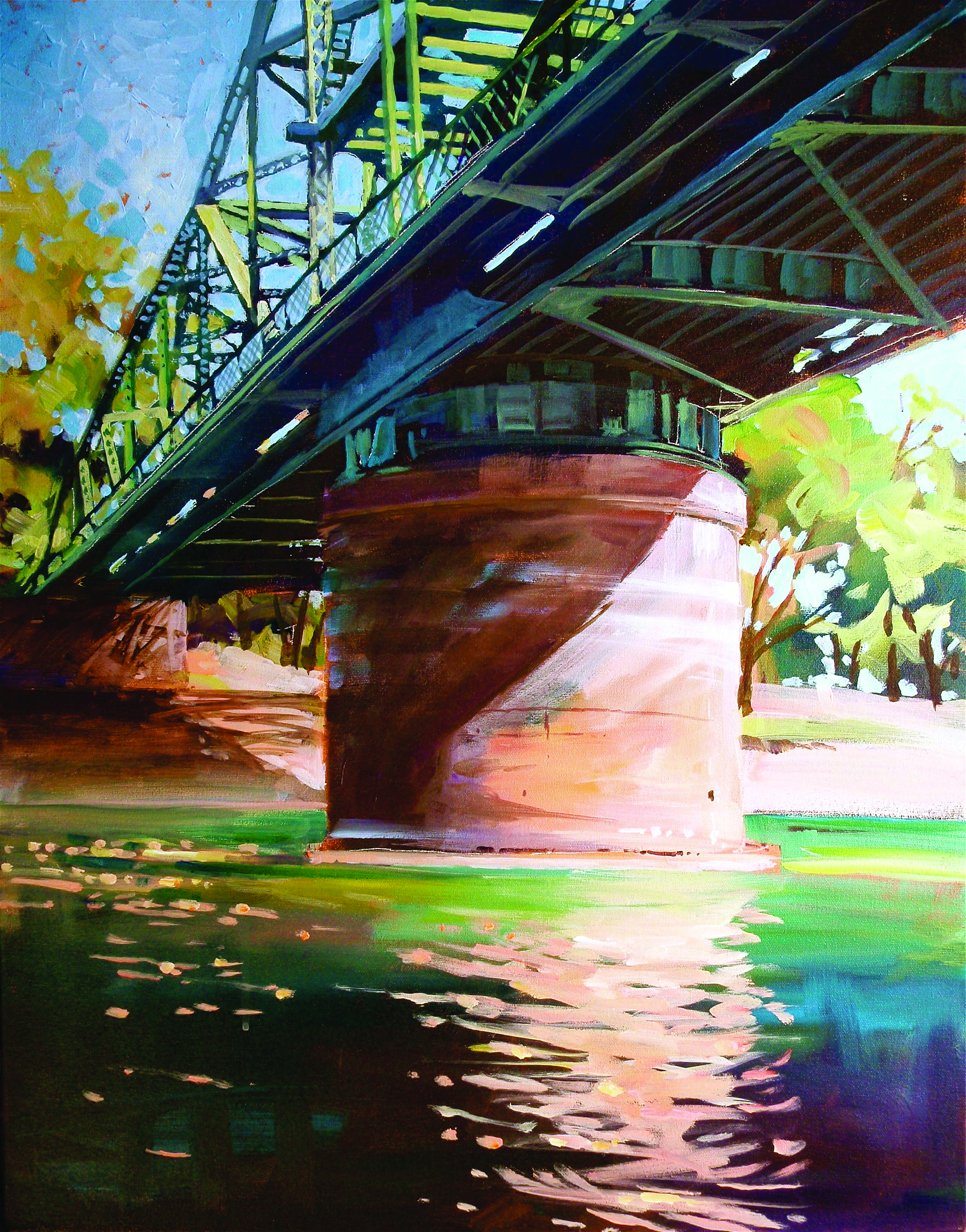

Although the artist most often uses acrylic paints in his studio, he does take them out on location when he wants to work with fast-drying, insoluble paints. “The key to keeping the paints from drying too quickly on the palette or on canvas is to spread the acrylics on a Masterson Sta-Wet palette and to use Golden’s Open acrylic titanium white,” Lobenberg advises. “I don’t use the full line of Open acrylics because they dry too slowly for me, but mixing the Open white with standard-formula acrylics gives me the properties I like.”

Lobenberg was introduced to another useful tool by Mike Bailey, a nationally known watercolorist: the Mr. Clean Magic Eraser, which is excellent for removing paint from paper. “It’s a handy tool for getting rid of mistakes or parts of a painting that aren’t working,” Lobenberg says. “I put the Magic Eraser in water, squeeze out the excess moisture, and pull it over the section of paper I want to clean up.” He also points out that a fellow artist showed him how one can paint around pieces of 3-M blue painters’ tape in the same way one might paint over paper coated with liquid frisket.

David Lobenberg became actively involved in plein air drawing and painting in 2003 after meeting artists Terry Miura and Susan Sarback. His portable equipment includes a folding canvas chair that has pockets for holding equipment, spiral-bound sketch pads, watercolor paper, and a small tripod or, for acrylics, a pochade box. “I place a priority on being able to set up quickly and get right to work on a drawing or painting,” says the artist. “I like the spontaneous, immediate quality of plein air paintings that record fleeting patterns of light and shadow. I want to have fun, so I travel light and plan on having fun.”

David Lobenberg became actively involved in plein air drawing and painting in 2003 after meeting artists Terry Miura and Susan Sarback. His portable equipment includes a folding canvas chair that has pockets for holding equipment, spiral-bound sketch pads, watercolor paper, and a small tripod or, for acrylics, a pochade box. “I place a priority on being able to set up quickly and get right to work on a drawing or painting,” says the artist. “I like the spontaneous, immediate quality of plein air paintings that record fleeting patterns of light and shadow. I want to have fun, so I travel light and plan on having fun.”

David Lobenberg was featured in the October-November 2014 issue of PleinAir Magazine.

Delicious Kelly. Inspiring. Finally examples that stimulate my juices. Thanks so much.

If you ever have a chance to take a workshop from David Lobenberg, DO IT! His enthusiasm is infectious and he provides invaluable tips on everything from technique to composition without ever sounding pedantic. Thanks for a wonderful article on his approach to Plein Aire painting.