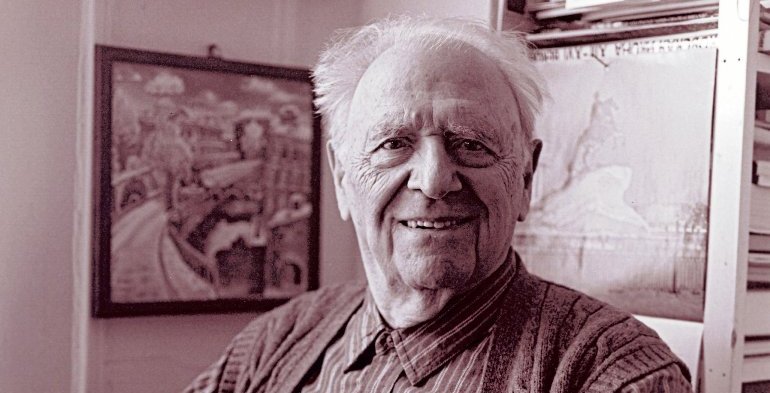

Despite suffering from macular degeneration, and almost completely losing his sight in his later years, Russian emigre painter Serge Hollerbach (1923 – 2021) painted well into his 90s. In this amazing film by The Vision and Art Project, the artist created two paintings, separated in time by a period of four years during which he had visibly aged and his vision had declined. While painting, he discussed art, his displacement during World War II, building a new life in New York City, and how vision loss affected his ability to paint.

The Artist’s Story in His Own Words

By Serge Hollerbach

My life as an artist has three periods. Two brief ones, Russian and European, and a long one – American. I was born in 1923 in Pushkin (suburb of Leningrad). As a child I drew constantly and was encouraged by my parents and my Uncle Eric Hollerbach, who was a well-known art and literary critic in Leningrad, USSR in 1920-30. He lived close to us and it was in his apartment that I saw for the first time examples of Russian art of 19th and 20th centuries, mainly portraits, engravings, and stage designs.

When I grew older I started to visit the famous Hermitage Museum in Leningrad and saw paintings by Rembrandt, Rubens and masters of Italian Renaissance. At the age of 17 I had decided to become a painter and switched from a regular high school to a special High School of Art that was a part of the Academy of Fine Arts in Leningrad. My studies at the High School of Art lasted, unfortunately, only six months. On June 22, 1941 Nazi Germany attacked Russia, the suburb of Leningrad where I lived was occupied and subsequently I spent the war years as a laborer in Germany where I was sent together with hundreds of thousands of Russian men and women to work in the fields and factories.

The American Army liberated me in May 1945, and in 1946, having decided not to return to Russia, I enrolled as a student in the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. For the first time I experienced the so-called “cultural shock”. If in the Russian High School of Art we spent hours and hours shading and correcting a drawing, in the Munich Academy we were literally “drilled” in quick linear drawing and expressionistic characterization of objects, be it still life, landscape or model. I had to abandon slow and tentative approach and to adapt myself to a fast, grueling “hit or miss” pace. We were supposed to accentuate shapes, angles, exaggerate colors, staying however within the limits of a heightened reality.

Two cardinal sins were a) copying reality “like it is” and b) going into wild, senseless experimentation with meaningless shapes and colors, not related to a given subject. Four years of studying in Munich (6-8 hours a day, no summer vacations) gave me the essential skills in drawing and painting and more importantly, the direction and an uncompromising attitude toward all that is opportunistic and conventional in art. It served me well in the years to come. I didn’t graduate; I had one more year to go, but my visa came up and in the fall of 1949 I came to New York determined to continue my studies and to embark on the career of a professional artist.

New York City, with its rich cultural life, its many museums, galleries and art schools, helped me to find myself as an artist. I started to exhibit in the late 1950’s and continued to do so not only in New York, but across the country and in Europe. Knowledge that “talent” is many different things helped me a great deal in teaching and conducting workshops. Indeed, there is no point in forcing a person to become a realistic, figurative painter when he/she is not gifted “that way”. Her or his strength may be in design in flat color arrangements. Such ability can be best applied to landscape or still life painting or to semi-abstract composition. It is the task of the instructor to find out what the inclination of every student is and to guide him or her to the realization of their potential.