Frank LaLumia offers his take on the contributions John Singer Sargent made to watercolor.

By Bob Bahr

Noted watercolor artist Frank LaLumia calls Sargent’s watercolors “a complete exercise of joy.” He revels in how Sargent embraced the limitations and unique opportunities watercolor allows an artist. “What is most remarkable to me is how Sargent employed the medium,” he says. “Sargent used watercolor in a way that was unique unto itself. Sargent had a natural understanding of watercolor — like he was born to it.”

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

1906-1907, opaque and translucent watercolor,

14 1/16 x 20 in.

Collection Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

LaLumia points plein air artists toward Sargent’s piece Mountain Fire, a relatively abstract depiction of a wildfire engulfing an alpine mountainside in smoke, a painting that owes a bit to Turner. “It’s a remarkable tour de force, showing smoke moving up the hillside, and the peaks affected by the diminished light,” LaLumia points out. The fire itself is indicated with just a few spots of bright red, while the scene is compressed and dominated by the smothering mass of white smoke. But LaLumia saves most of his words for Sargent’s portrayal of sunlight.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

1906, translucent watercolor and touches of opaque watercolor with graphite underdrawing,

21 3/16 x 14 3/8 in.

Collection Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York.

“He used the medium of watercolor in a conscious way to show what is unique to it,” says LaLumia. “I’m sure he’d do a great job painting this in oil, but it couldn’t be better than this.”

“One of the great epiphanies on the art road is the realization that we are painting light, not things,” says LaLumia. “Sargent knew this like no other. I love how Sargent handles dappled light. A good example is In a Medici Villa. The very nature of dappled light — the many pieces of dark and light — can compromise the value structure, leaving a painting looking like a series of dark marks on a light field, or vice versa. The way Sargent handled it, the composition comes together rather than falls apart. His value plan is solid. He uses color temperature to create a palpable feeling of sunlight.”

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

1909, translucent and opaque watercolor with graphite

underdrawing, 15 7/8 x 20 7/8 in.

Collection Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston, MA

And certainly the painting Corfu: Lights and Shadows perfectly showcases Sargent’s handling of light. For this piece, Sargent chose as his subject an unassuming outbuilding — but the building’s white walls provide a canvas for the artist’s exploration of color and light. “That piece has a light unto itself,” LaLumia asserts. “A white object in sunlight is like a laboratory for studying light. His ability to see light and translate that to a relatively simple watercolor technique is amazing.”

Sargent pushed and prodded the most out of his watercolor supplies. By the time he painted this group of paintings (1902 to 1912), art materials manufacturers were offering watercolors in tubes and paper in pre-stretched blocks, and collapsible easels and suitable umbrellas were available for plein air work.

Watercolor pans were advanced enough to offer moist cakes for easy loading of the brush, and a variety of mediums were sold to help artists customize the performance of their pigments.

Sargent cut and scraped the paper, applied layers of color (especially Chinese white) so thick they cracked upon drying, frothed the paint so vigorously it left bubbles on the paper that popped to leave bright spots of near-white, applied wax with a stick to resist washes, and stepped up highlights with zinc white. His watercolors would not meet the tough restrictions some contemporary transparent watercolor associations require of competition entries. He used graphite pencils to lay down underdrawings on exacting elements such as buildings, and applied graphite lines at the very last, on top of largely finished watercolor paintings, to indicate facial features in figure paintings.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

1908, opaque and translucent watercolor with graphite underdrawing, 14 x 22 in.

Collection Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

“This is such an incredibly difficult thing to pull off,” says Frank LaLumia, a contemporary watercolorist and plein air painter. “It’s just a chaos of trees and gourds, which makes it so amazing that the painting hangs together so nicely. The background forms big shapes when you squint, creating the perfect foil for the subject of interest.”

He freely mixed opaque and translucent colors as the situation demanded. In Salmon River (not shown) Sargent laid down an opaque green for the river’s base color, then mixed Chinese white with blues and greens for strokes indicating turbulent water and waves. In Gourds, he turned the conventional approach upside down, painting the background foliage in sharp strokes full of contrast while gently washing muted colors into the gourds — his center of interest. When Sargent showed a few of his watercolors in London, traditionalists felt affronted.

“The difference between Sargent’s approach to watercolor and the British watercolor tradition was profound, a fact that became even more evident when Sargent showed five of his works at the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours in the summer of 1904,” write Hirshler and Carbone in the catalogue for “John Singer Sargent Watercolors.” “The liberal Westminister Gazette compared Sargent’s arrival to that of ‘an eagle in a dove-cote,’ conjuring a compelling image of the painter’s bold command of the medium and the unsettling effect it must have had on more conventional (and perhaps more timid) practitioners.” By the time of his death in 1925, Sargent was seen as hopelessly antique by fans of modern movements such as Cubism, but it would take considerable obstinacy to refuse to see the modern sensibility and innovation in Sargent’s watercolors.

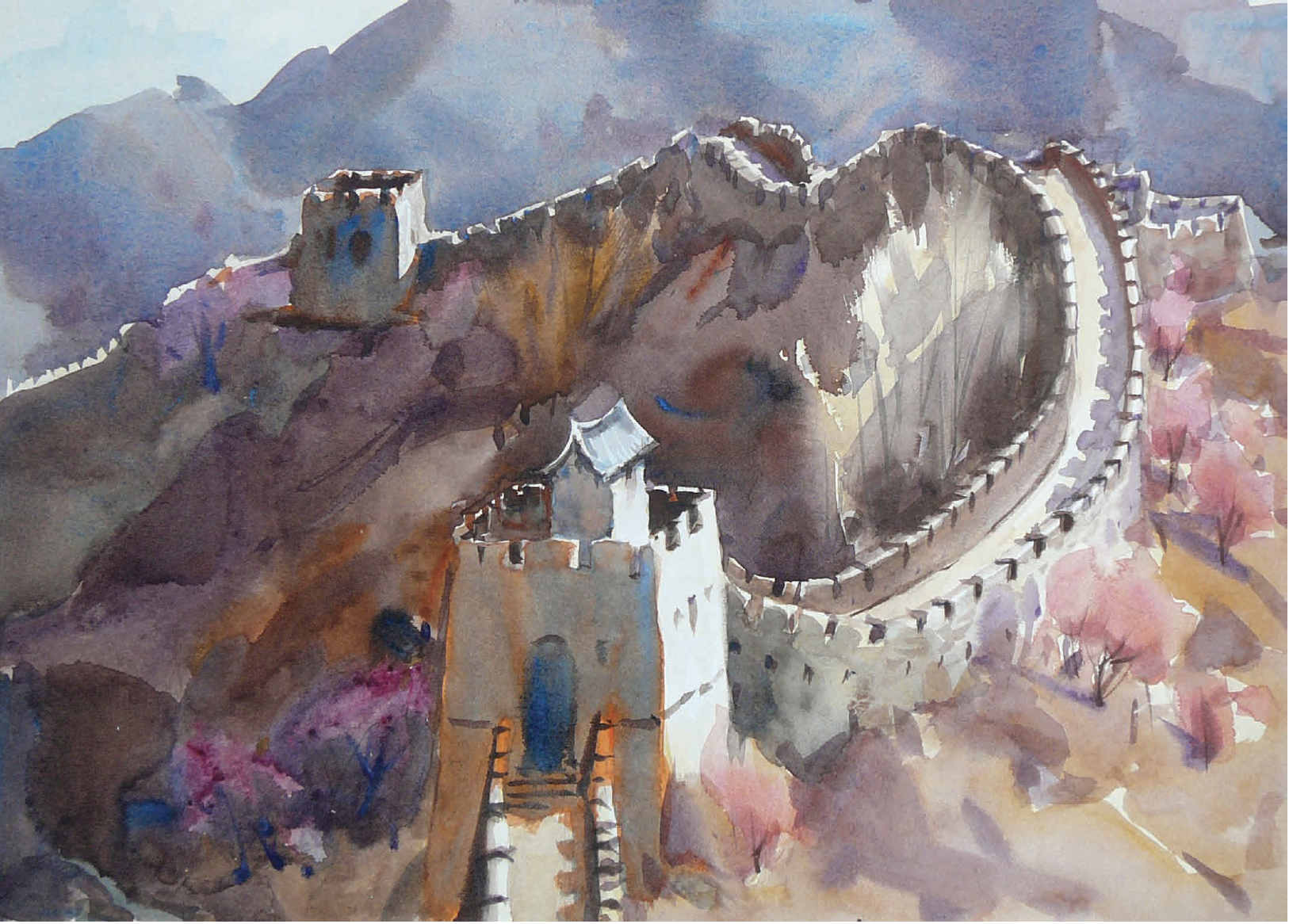

Watercolor Paintings by Frank LaLumia

Frank LaLumia

2010, watercolor,

22 x 15 in.

Collection the artist

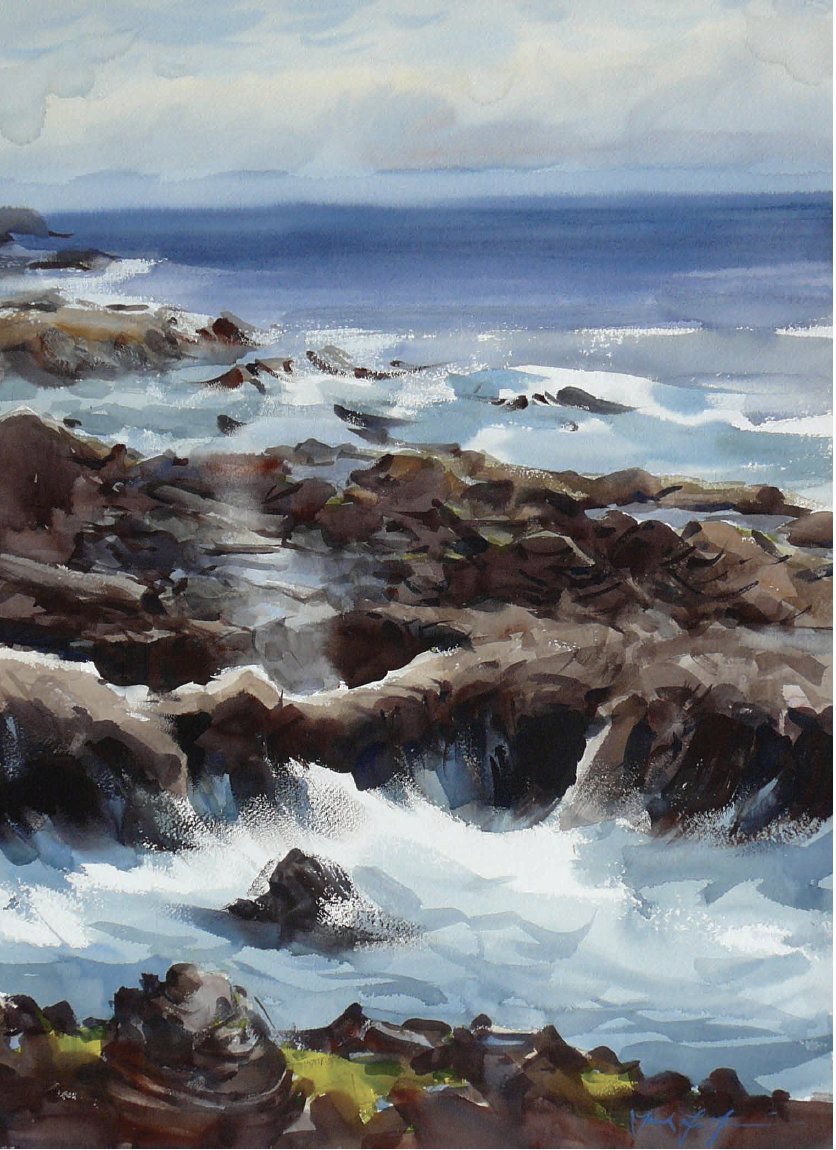

Frank LaLumia

1992, watercolor, 15 x 11 in.

Collection the artist

Plein air

“This watercolor was painted on a Sunday afternoon in spring,” says the artist. “It’s funny what you remember after all these years. In a lot of ways, it is a classic plein air painting in that its look and level of finish is dictated by the conditions on the ground. A curious Sunday crowd was something of a distraction; the light, a filtered overcast, was threatening to turn dark; the humidity was favorable.”

Frank LaLumia

1992, watercolor, 11 x 15 in.

Collection the artist

Plein air

Frank LaLumia

2010, watercolor, 30 x 22 in.

Collection the artist

Plein air

“Few activities are more exhilarating than painting a full-sheet watercolor en plein air on the coast,” says LaLumia. “The humidity somewhat mitigates the added difficulty of painting a watercolor of this size. Even so, it is a full-out sprint, and getting a good one is made even sweeter.”

For more inspiring stories like this one, sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Wonderful article on John Singer Sargent by Frank Lalumia. Thank you!

Beautiful, and such detailed discussion, very interesting. I was fortunate to see the places in China he painted before travel restrictions. Lov the Great Wall painting so free. Loose and colourful. We will never stop learning from Sergent, the fire on the hillside is masterful.

Thank you for your thoughts on Sargent’s work. He made it work and is an inspiration to us forever! The light in his paintings is just stunning and i am so glad he loved watercolor so much!

Love your Spouting Horn at Cape Perpetua in Oregon! It’s a beautiful coastal scene and Sargent is one of my favorites.

Huge fan of Sargent! Thank you for sharing! I enjoyed his work so much; I did a master study of one of his Bedouin paintings.

I’m enamored with this artist’s work. Simply love it. Profoundly talented. He makes the simple so profound, without losing its simplicity. To see his work is to know that you’re in the presence of greatness. I’ve never heard of him before now. Must research to know his story. Thank you.

[…] Sargent’s Greatest Lessons – American Watercolor […]