Choosing a good composition can be challenging, and it is something that I take it seriously when I paint on location. Compositional possibilities are endless, and it can be daunting to choose the right one. I find it helpful to take some time beforehand to do a few thumbnail sketches to play with different composition ideas and see which one will work best from an aesthetic point of view. Before opening my sketchbook, I have to remind myself that the composition is not only about design but also about effectively representing my intended narrative. Some of the preliminary questions I ask myself are: What in the subject grabs me the most? How do I paint that? How do I want to communicate my impression of the scene? After that, I make sketches with the following design options in mind: horizontal or vertical format, higher or lower horizon, zoomed in or zoomed out, higher or lower eye level.

Deciding Where to Put Your Focus

In the photo above, you can see the scene I was faced with — a small beach scene with a lot of boats and canoes and a few people. In the background there is an urban skyline across the bay. I liked the subject’s general theme, the layers of depth, and the sunny day feel of the scene. The fact that there was something interesting in each of the three planes also appealed to me. But what interested me the most was the activities taking place on the beach, so I decided to put the focus on the foreground.

Composition Idea 1: The horizontal composition is the most commonly utilized in a landscape or a seascape. The result may look a little cliché, but it seems fitting and works most of the time. I made two sketches in a horizontal format. Both sketches are almost an exact depiction of the scene. The difference between the two is the horizon level, with one being a little higher than the other to enhance the expanse of the bay.

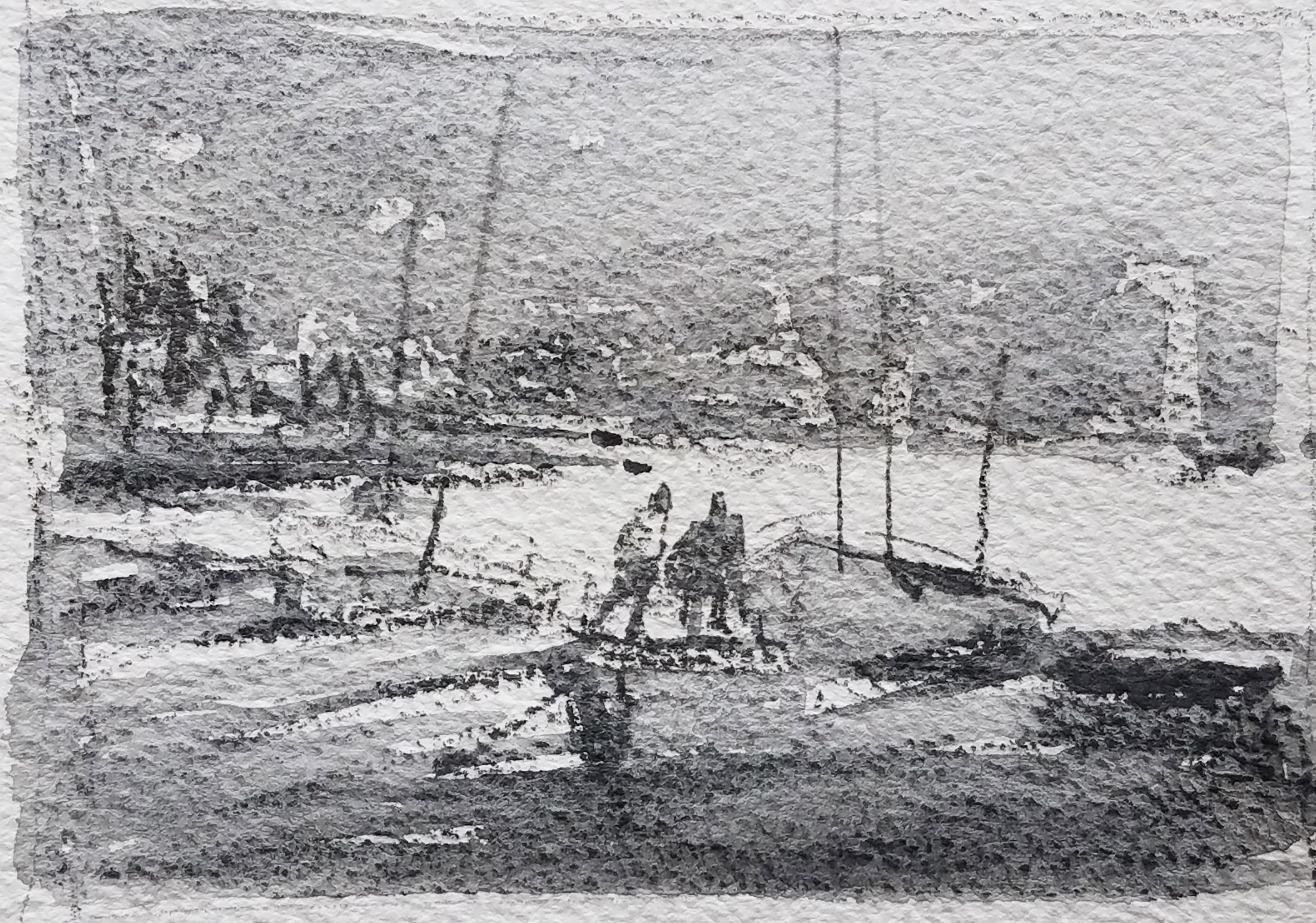

Composition Idea 2: I narrowed the focus and took the middle vertical section in the scene for this sketch. This way, figures on the beach can be shown slightly larger and attract more attention. Because I can keep three ground levels (beach, island in the mid section, city in the back) on the same picture plane, this composition creates depth in a painting. I can also avoid too much repetition with trees on the island and boats on the beach. Unlike the first two horizontal sketches, this composition is more unique and exciting, yet retains all the elements that I wanted to incorporate.

Composition Idea 3: Since the most important area was the foreground, I decided to push the horizon outside the painting to eliminate most of the mid ground and the background altogether. Reducing the elements from the typical three planes to two or one simplifies the composition and makes it more powerful. Although I liked the result in this sketch, part of the appeal of this view was a sunny sky and the depth of the landscape. I feel this idea doesn’t reflect my initial intent.

Ultimately, I decided to create a painting from the second idea using a vertical format. Although any of these sketches would have worked, the second idea was the closest to my initial response to the landscape. While principles such as the one-third rule are helpful to know when making compositional decisions, I believe developing a strong sense of design is equally important to be able to intuitively change the existing composition. I recommend doing a few thumbnail sketches to choose the composition that looks the strongest and most closely resembles your initial response to the subject.

I share more of my tips and techniques in the DVD, “Storytelling With Watercolor With Keiko Tanabe.”

Thanks for the knowledge

This is very helpful. I like the way you painted the city scene and the grayed sky. I never would have thought of that.

[…] Using Composition to Tell Your Story, American Watercolor Weekly (February 26, 2019) […]