By James Lancel McElhinney

Serious landscape painters are no strangers to the perils and inconveniences of working outdoors. Most of us have been drenched by cloudbursts, pummeled by hailstorms, vexed by insects, or pestered by gawkers. During one of his visits to the Andes, American painter Frederic Edwin Church lost a cache of sketches and notebooks when the burro carrying his luggage stumbled and plunged off a precipice. British watercolorist Tony Foster belongs to that rare breed of expeditionary artists — from Jacques le Moyne and John White to William Hodges, Marianne North, and Adrian Wilson, who perished with R.F. Scott in the Antarctic, leaving a notebook filled with exquisite watercolors. Like a modern Ulysses, J.M.W. Turner had himself lashed to the mast of a storm-tossed ship to experience the Sublime firsthand.

North American subjects comprise a large share of Foster’s oeuvre, from paddling the Merrimack River in the wake of Thoreau to hiking the length of the John Muir Trail and following the route of Lewis & Clark from the Mississippi to the Pacific. I asked him how it all began.

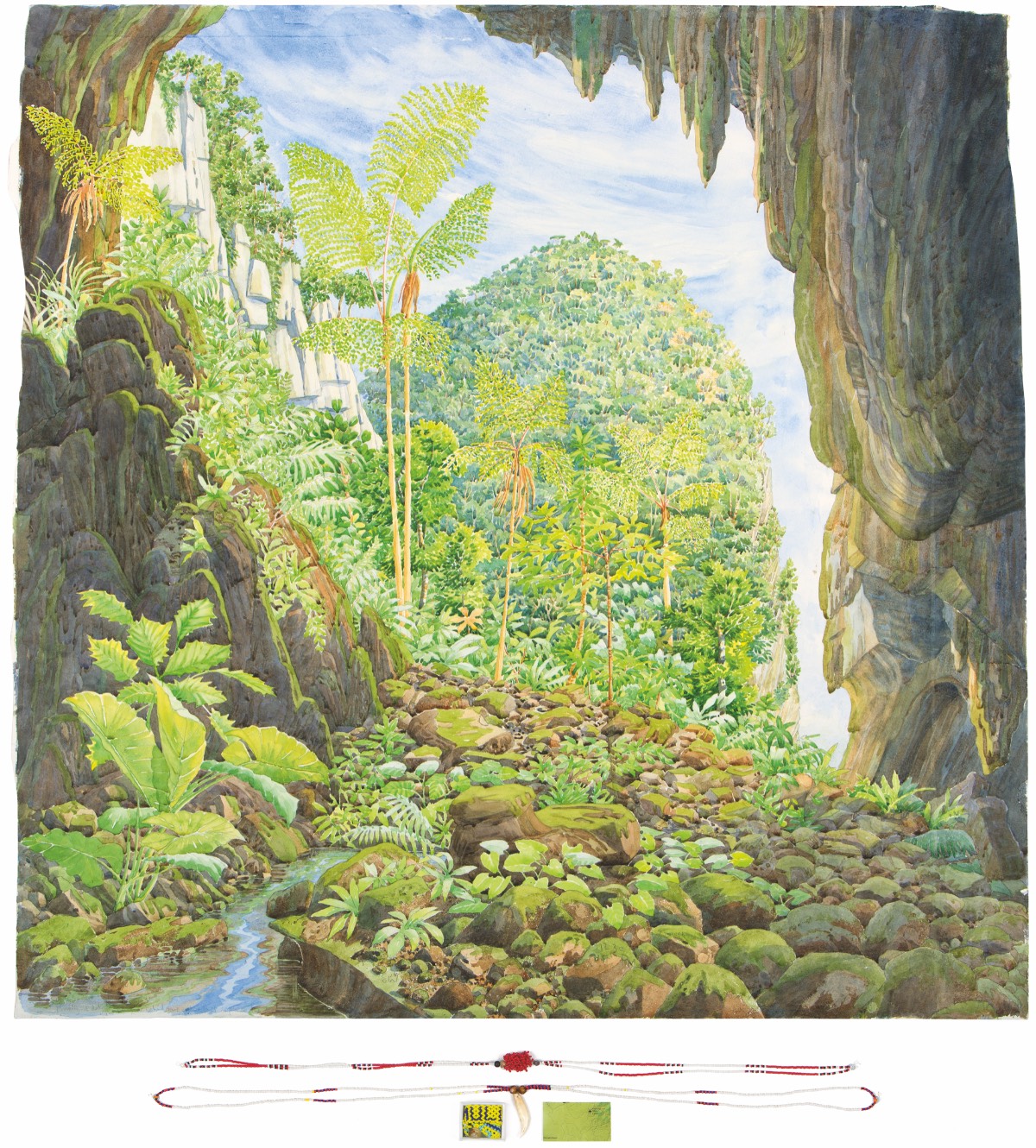

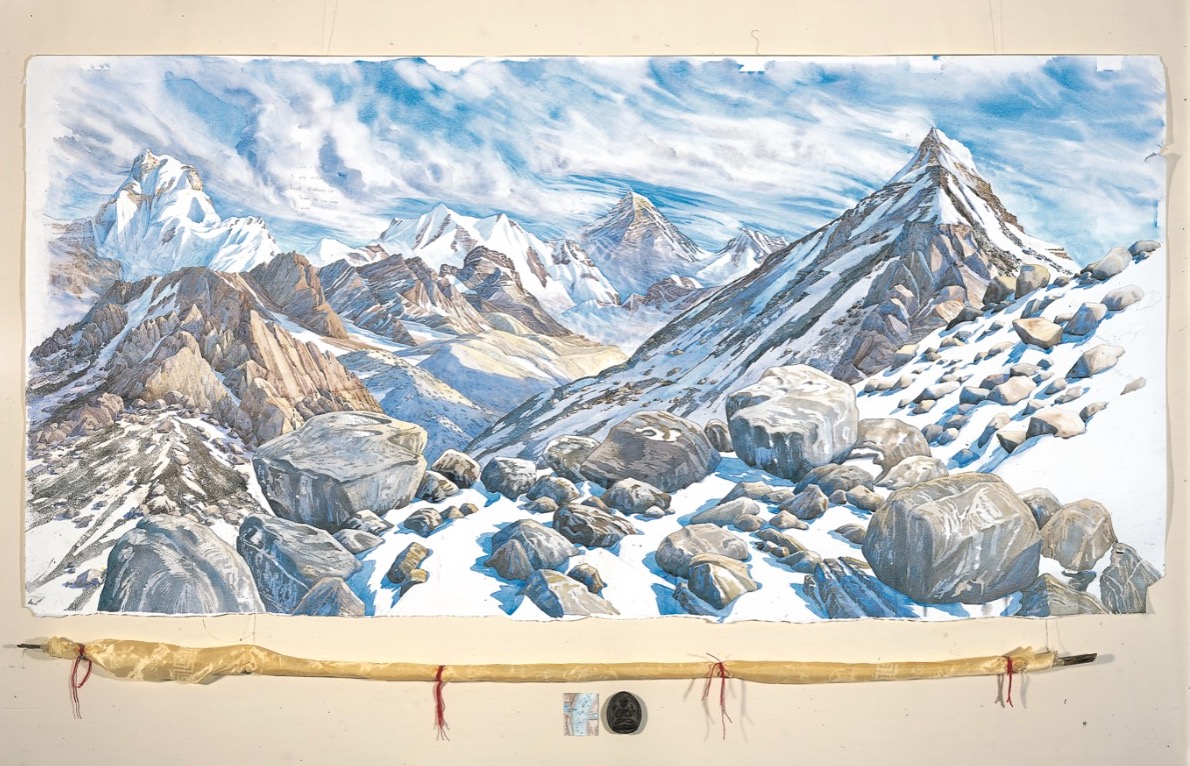

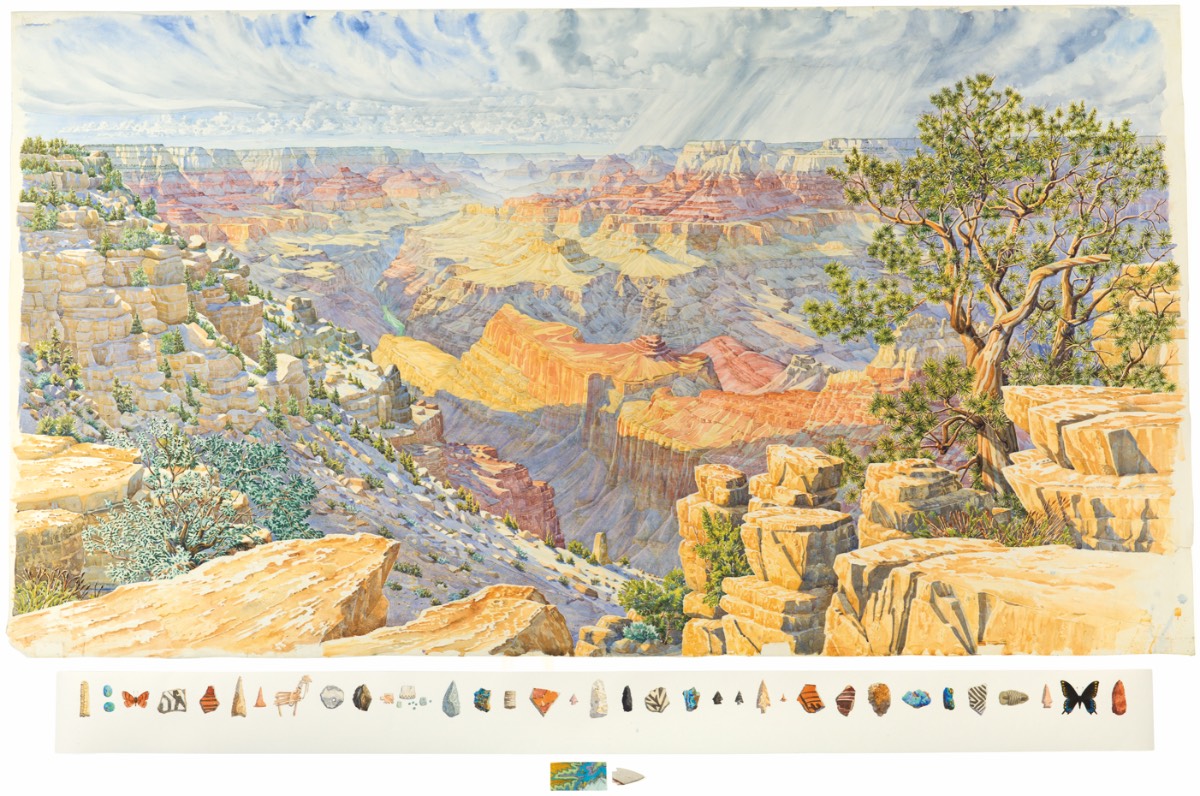

“I like to be outdoors,” he replied. “I like to go hiking and traveling … adventure, being in wild places. I thought, perhaps I can do paintings about that. So, I started off by just doing quite modest journeys across Dartmoor for a few days … usually with a couple of friends … got caught in a bog … rain came pouring down. Somehow, I realized that people were actually more interested in the stories than they were in the paintings. I thought perhaps I should incorporate those stories into the work. So I began to include maps and found objects and notes about other things, as well as the landscape. This gradually developed until it became my absolute way of working.”

In this way, Foster embraced the role of visual storyteller. Following historic itineraries, he retraced the footsteps of explorers and naturalists along familiar routes and into the wild.

In 1984, having decided to produce an exhibition about Thoreau’s 1839 excursion down the Concord River and the Middlesex Canal into the Merrimack River, Foster packed his bags, went to Concord, and retraced the journey. He then headed to Maine to canoe the Penobscot and the Allagash, with its circuit of lakes and portages that lead to Mount Katahdin.

“It was at that point I realized that wilderness existed. Up until then, I didn’t. You know … wilderness isn’t really a European concept … all of Europe has been trampled over, and fought over, and owned by people for thousands of years really. In a sense, I know that America has, too. Nonetheless, it seemed to me that these vast areas … appeared to be almost completely untouched. I know that some of it was second growth, but to European eyes, it had that appearance of being wild country. I sort of fell in love with the idea … these wild places that appeared untouched, and so that became my guiding principle … working in these extraordinary places which had the appearance of nature being completely predominant.” Foster’s journeys are thus like pilgrimages to pay homage to unsullied nature.

MATERIAL MATTERS

Foster says his painting gear consists mostly of a Winsor & Newton pocket-sized bijou-box, a Tupperware-lid palette, sheets of paper carried in a waterproof aluminum tube, a large drawing board, and a collapsible camp stool. He spends considerable time planning the route, calculating the quantity of supplies required to traverse any given distance, and setting resupply points along the way.

James Lancel McElhinney is a maker, blogger, and author of Sketchbook Traveler, a series of books exploring terrain, history, and the environment through drawing and writing. This material was excerpted from an article in the July-August 2022 issue of Fine Art Connoisseur.