By Bob Bahr

Poppy Balser’s watercolors give the viewer a sense of wide open spaces. Even if the subject is a farmers’ market, one never feels cramped. For Balser, the editing out of clutter that may give the scene a more closed-in feel is second nature. She is not a city person.

Having a predilection for open spaces would explain part of the airy feeling in her watercolor paintings. Another reason would be that she usually offers a hint of what lies beyond, thus giving the scene depth. This, too, originates in her personality. “I’m always wondering what’s around the next corner,” she says. “I never look behind me. I want to know what’s next. I am anticipating the future and I am always hopeful about it — I generally have an optimistic outlook. I try not to dwell on the past because there’s not much I can do about it. One can only go forward and make progress.”

As a result, the background or middle ground in her watercolor paintings always have some opening to another plane. “I like to show what I can see through the trees, what’s beyond. That’s because I want to go around the corner and see what’s around the bend!” Additionally, Balser keeps the foreground clean to offer an open path into the painting for the viewer. “I edit stuff out when I’m painting, and often I leave the foreground clutter out,” she confirms.

Watercolor Tutorial

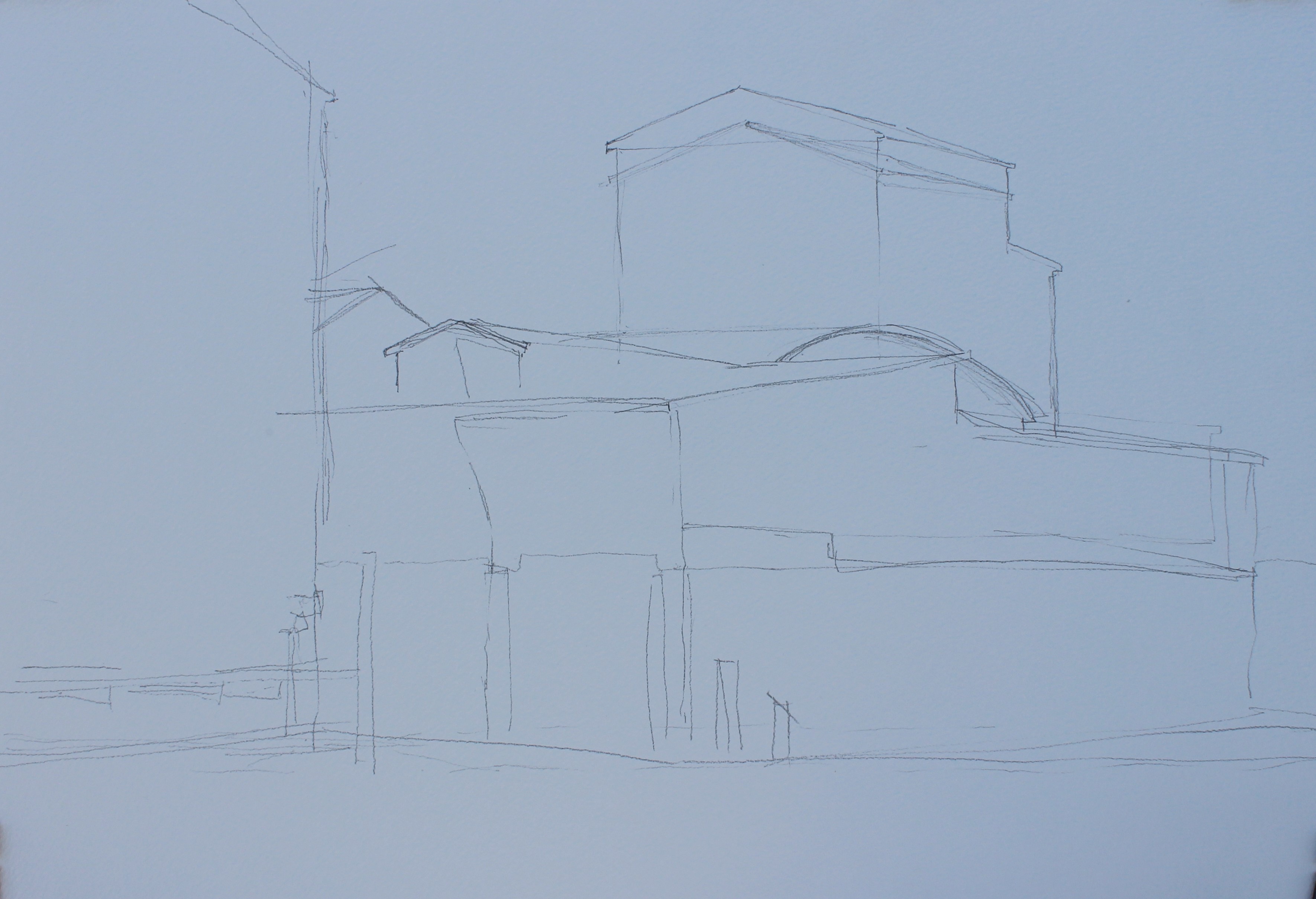

Step 1: Poppy Balser starts a watercolor painting with a drawing identifying those areas that are to remain light or white. As this is the drawing for a value sketch, and not the finished painting, it can be a very rough drawing; some of Balser’s corrections are clearly visible in the photo.

Step 2: The value sketch measures 15 x 22 inches, the same dimensions as the intended final painting. Balser used a mix of ultramarine blue and burnt sienna to give a sense of the shapes and light in the scene. This process, drawing to completion as shown above, took roughly half an hour.

Step 3: After assessing the value sketch, Balser transfers her drawing onto a new sheet of paper for her actual painting, only marking those details that were crucial. She set up her value sketch where she could refer to it as well as the scene before her. Then Balser mixed puddles of paint, one for the sky and a warmer and cooler puddle of colors for the shaded sides of the buildings. She then applied these puddles, painting around the sunlit areas for now, letting the different color blocks run together on the paper. Balser paints mostly vertically in the field; one can see how she worked her way down the page.

Step 4: The first wash has now covered most of the paper, except for those areas that are to remain white or close to white. This wash looks dark here, but that is a quality of watercolor — it will lighten significantly as it dries.

Step 5: As the initial wash dries, Balser paints in deeper- valued areas to create shaded areas between the pilings, and to give form to the buildings. At this point, the light had moved completely off the buildings and the water and the tide had gone out too far for her to paint the water reflecting the buildings, so the artist packed up, planning to return at a similar time the next day.

Step 6: Returning for the second session, Balser established darker values in the shaded areas. She finds painting pilings to be a subtractive process: Start with everything light in value and then subtract out all the space around the posts and beams by painting in the dark areas between them.

Step 7: With a combination of dragged dry brushstrokes and highly colored glazes, Balser gave some texture to the posts.

Step 8: The artist refers to this stage as “getting lost in the details.” Given the rapid movement of light and tide, she suggested the pattern of the pilings instead of carefully painting them exactly as they were.

Step 9: Now that the central focus of the light on the buildings and pilings had been captured, Balser worked out to the edges of her paper, suggesting the forms and shapes more than carefully detailing each element.

Step 10: The last challenge was the water, which with the receding tide and sporadic breezes changed from minute to minute. Working mostly from memory and experience, the artist laid in a pattern of ripples to give a sense of the moving water within a sheltered harbor in Last Light on the Casey Building (watercolor, 15 x 22 in.).

Poppy Balser has been painting in earnest since 2000 and learned her craft through studies with renowned instructors in watercolour and other mediums. These instructors include William Rogers, Chris Gorey, Stapleton Kearns and Jean Pederson. She is a full time professional artist with a part time job as a pharmacist. As well as being an artist and a pharmacist, Poppy Balser is the mother of two children. She has been blogging about being a painter in Nova Scotia since 2008. She was featured in the August-September 2016 issue of PleinAir Magazine.

Paint with Poppy at the 2020 Plein Air Convention & Expo in Denver, Colorado, May 2-6.