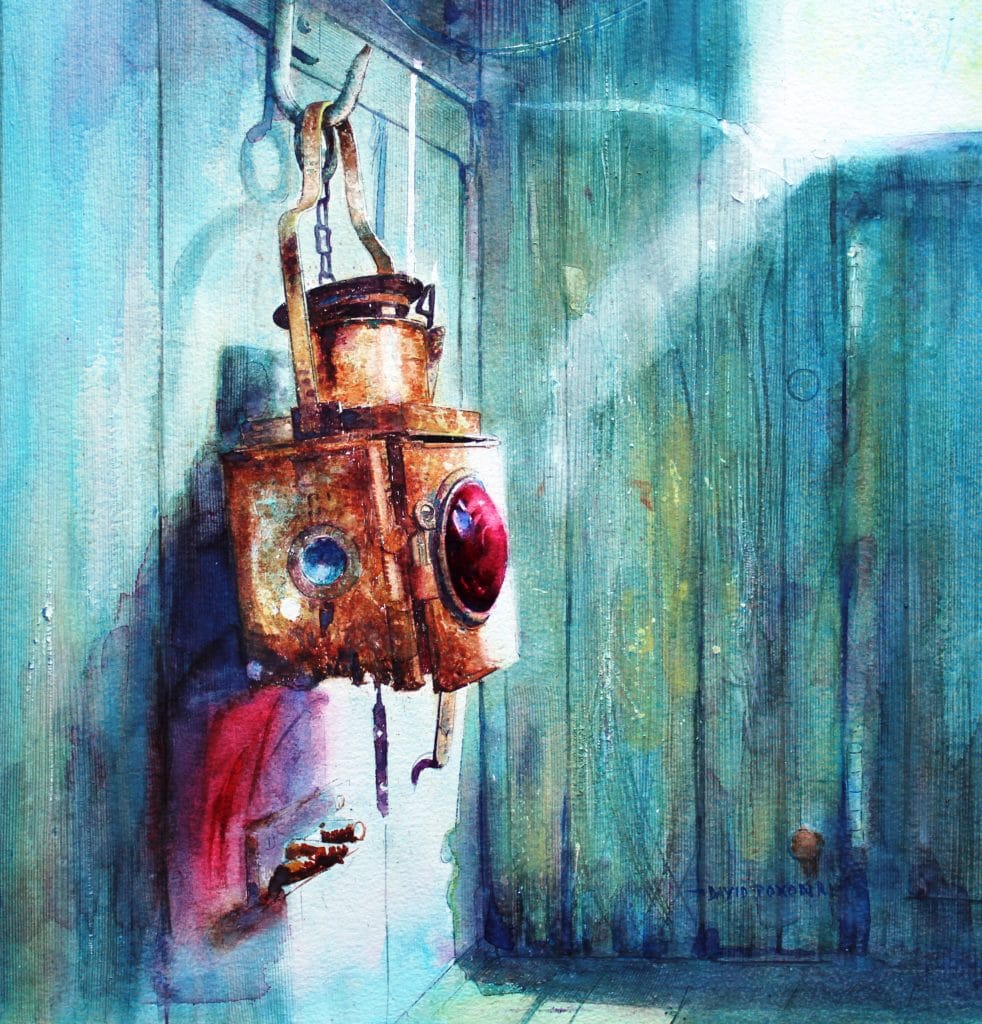

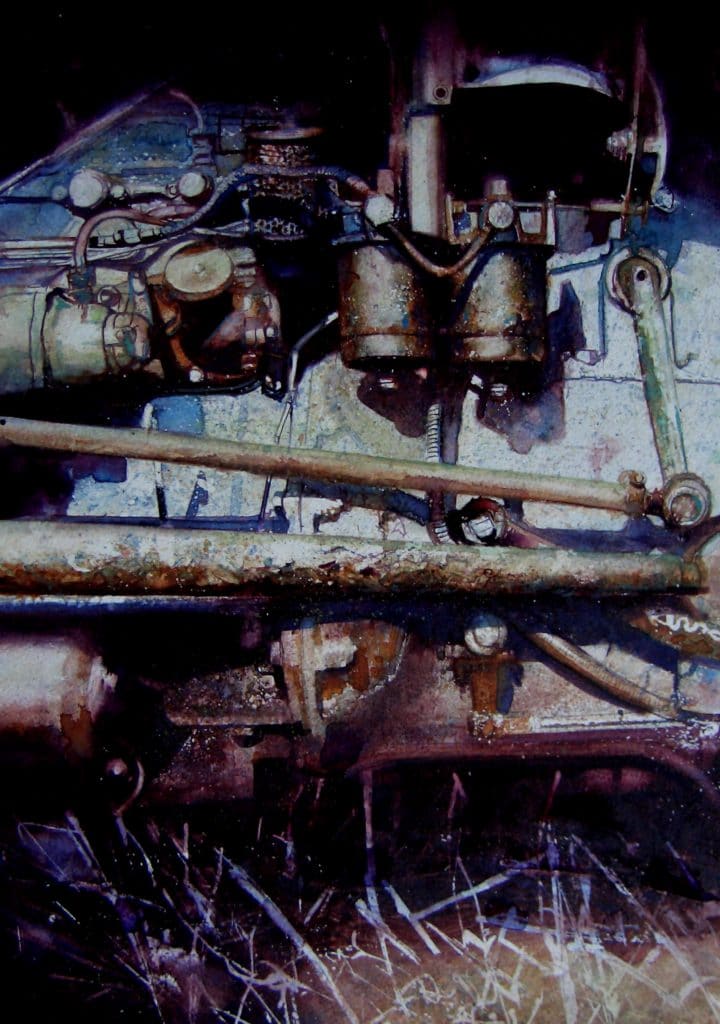

English watercolor artist David Poxon finds inspiration in well-worn tools and machinery. For some, transparent watercolor may seem like an odd medium for depicting such rugged subject matter, but for Poxon, the choice is a natural. Here, he describes how he emphasizes the light hitting his subjects and capitalizes on the best qualities of pure watercolor to capture the beauty in humble hardware.

My Watercolor Process

By David Poxon

My medium of preference is watercolor, and I am a purist in the sense that I use mainly transparent colors, avoiding white paint. I aim to record what is seen and felt in a subject as accurately and realistically as possible, believing that any finished painting should attempt to transcend a mere visual experience and reach out to the viewer in a stimulating, emotional, and engaging way. Dealing with the technical challenges that pure watercolor painting presents, requires patience and preparation. Thinking about the subject whilst exploring its ‘construction’ through drawing, and refining and rehearsing passages that stretch my abilities as a painter, provides my constant motivation. This reverential approach is very much born out of the respect I feel for the subjects that call me.

Finding Subject Matter

Subject hunting trips are usually frantic and fast-paced expeditions. I go armed with a small sketchpad, drawing kit, camera, and tape measure to record size and scale. When the light is right for me—with strong cast shadows and tonal definition—I am ready to go exploring at a moments notice. Being aware of potential subjects is very much a state of mind; inspiration can strike in the unlikeliest places, and it’s important to have my artist’s radar on maximum alert.

I never rearrange a possible subject, as this can give an artificial atmosphere to the work, rather I change my position within the subject area until a sense of the painterly possibilities emerges. I move rapidly from one scenario to another—stopping to make quick drawing notes, taking photos for fine detail, and measuring where necessary. Occasionally a more formal on the spot drawing is called for. Frottage (creating a rubbing of a textured surface using a pencil or other drawing material) is a useful technique to have in your armory to instantly create an impression of texture, shape, and tonal extremes. Any object you find can be captured in a few moments with the aid of copy paper and a soft pencil.

Getting the Drawing Right

It’s only later when back in my studio that the day’s collection can be fully examined. As my painting method means that days or weeks are spent on a work, it’s necessary to gauge whether my enthusiasm for what at first seemed like a good capture will sustain. Some projects are far more complicated than others, and this is where accurate drawing and preparation are vital. There can be no obvious drawing errors when attempting to record the parts of engines or tractors, as it’s inevitable that an expert will be in the gallery and spot any embarrassing mistakes. Taking time to get the drawing right will avoid a world of pain later. These machines and mechanisms have characters of their own, and I treat my depictions of them as portraits. The next step is to produce an accurate line drawing. I always work on stretched heavy watercolor paper, held down on to marine plywood boards. I keep a stock of various sizes available so that my options are never restricted.

My final line drawing for transfer to the watercolor paper will be kept to an absolute minimum in terms of detail. The aim is to provide a simple skeleton shape. I regard this very much as scaffolding in the sense that when the painting is begun, my process will rebuild the subject on the paper. The next step is protecting areas to be kept white. I use anything that comes to hand to do this—scraps of paper, objects, and masking fluid. It’s better to protect more whites than you may need, after all there are very few actual real whites in nature, and I can blend them away later in the painting if they are unnecessary. At this stage the ‘work’ does not look anything like it might end up, holding onto that final vision in the mind is vital.

Adding Color

First washes tend to be splashy affairs with mixes about the consistency of milk. I try to get 7 or 8 layers of wash down wet-on-dry to get paint body onto the paper. These washes are exploratory in the sense that a finished work may have more than 20 transparent layers. The drawing may become lost amid the seeming chaos of these first applications; finding the scaffolding drawing sometimes requires the tenacity of an archaeologist. Knowing where you want the painting to go only comes through experience with this type of method. I keep my board flat to maximize any granulation effects, rocking it occasionally to encourage runs and blending. Texture is important to me, so I will take any benefits the pigments throw my way. Balancing the medium’s natural tendencies while exploiting light effects, counter-balanced with complementary darker passages, is an exciting juggling skill.

Watercolor has a reputation for being the most difficult medium to master; it often seems to have a will of it’s own. With experience, you can limit the chances of the paint running away from your subject and wield a certain amount of control by stepping down through the tonal register with multiple layers of wash, working light to dark, and slowly steering the painting towards the vision that first inspired you. This patient approach can be very rewarding; after all, life teaches us that you only get out of something what you put in.

David Poxon is the author of Watercolour Heart & Soul, a collection of the artist’s most iconic paintings, together with a detailed section describing his techniques.

For more inspiring stories like this one, sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Just love this on-line educational interesting newsletter without leaving my home! Thanks for these free newsletters!

Nice

[…] Image Source […]

[…] Image Source […]