“Good paintings teach a watercolorist very little,” says Iain Stewart. “It’s the bad paintings that instruct me how to improve my work because I have to look critically at them to identify the reasons they failed. Too many artists focus on creating masterpieces, and they are crushed when they are not successful. In my experience as a painter and teacher, plein air watercolors are more successful when artists risk failure, paint with abandon, and then evaluate the results.”

Stewart has several recommendations to help watercolor artists go from risk-taking to successful paintings. The first is that artists should work from life to learn the way light works, how shadows move across the landscape, what different lighting and atmospheric conditions they might encounter, and when they might inject what isn’t there into their paintings.

“Watercolor is uniquely suited for this task, as light is reserved from the first brushstroke and must be protected throughout the painting process,” says the artist. “It’s very much like a game of chess, in that the more moves one plans in advance, the better the result. I am most often motivated by capturing a definitive lighting condition and how it influences shapes and values rather than by the intention of faithfully representing the subject as witnessed.

“The more one makes observations from nature, whether recorded in a sketchbook or an easel painting, the easier it will be to jump to the imagined. The underlying narrative in my work is not based on any theme or the identity of the subject, but, quite simply, how ‘place’ is inhabited and used daily.”

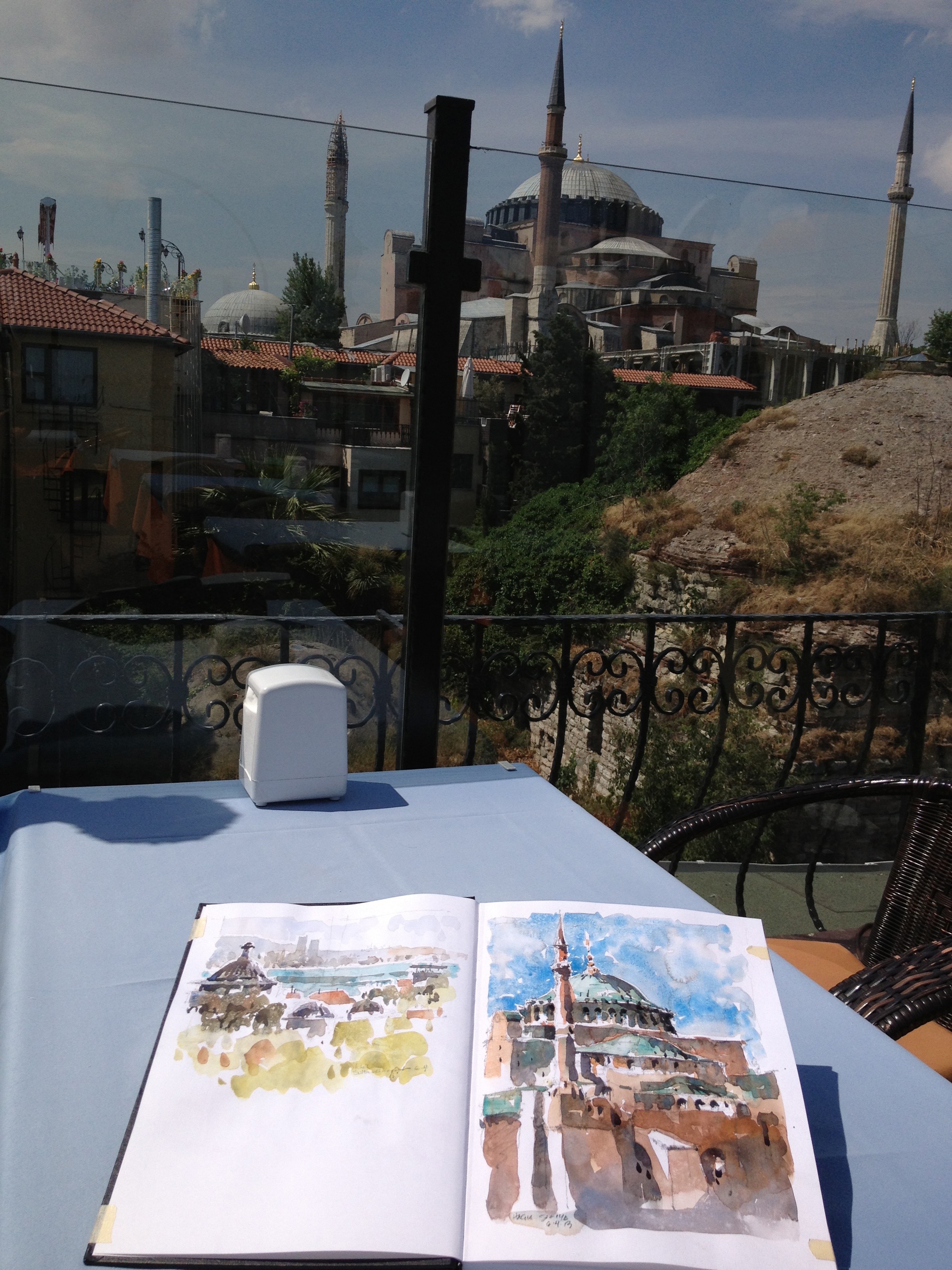

The process by which Stewart balances the risk of failure with a desire to capture the sense of place begins with thumbnail sketches in a small sketchbook. “I make one or two quick thumbnail value sketches in an effort to identify big shapes I can work into a composition,” he explains. “It’s a way of warming up, the way a musician might practice scales oran athlete would do stretching exercises. I can’t just walk up to my easel and paint. I need to move elements within the scene to make the painting stronger. I reduce those elements to the essentials, discarding what is unnecessary, and then adding useful elements.”

THE ARTIST’S PROCESS

After these warmup exercises, Stewart goes through a three- or four-step process to complete a watercolor. First, he applies a fluid, transparent, variegated wash of several colors over the paper in all areas except where he needs to save the white surface for the highlights. The mood of the piece is established right from this beginning stage.

Step two is carving out big shapes to define the scale and proportional relationship of buildings, roads, or other forms within the pictorial space. “I paint the most obvious shapes while keeping in mind how I am going to highlight the subject,” Stewart explains. “I don’t want other elements within the image to compete with what is important. At each stage, I increase the strength and viscosity of the watercolor paint. I’m always thinking about reflected light, the impact of complementary colors, and the sense of space indicated by warm and cool colors. Flat areas don’t please me, so I make a point of turning the forms to suggest the surfaces moving toward and away from the viewer, and letting the shadows breathe by keeping them transparent and varied in color and value.

“Finally, I define the shadows, darkest darks, and details and step away from the easel or turn the paper upside down to judge how well the abstract composition is working. At times a painting will need to rest before I continue working on it. At any given time, I may have three to five paintings in different stages of completion in my studio. That allows me to let my mind rest and return to see it with a fresh eye.”

Iain Stewart shares more of his watercolor tips and advice in his PaintTube.tv video workshop, “Higher Level Sketching.”

Kelly… I’m somewhat new to “ serious” painting. I don’t paint everyday, but most days. I take classes with various local instructors, soak up dozens of tutorials on the internet. I have attended and contracted for more. I joined the local watercolor society. I have a huge envelope filled with “learning experiences”. A few, very few hang on my walls. I love the process even while most end up in the “black hole envelope “. I greatly appreciate the comments you gather from successful painters. I learn something from every interview. Thank you for doing what you do.

This is a marvelous lesson with inspiring paintings to accompany it! Seeing failed paintings as learning opportunities is so critical to staying encouraged in the learning process.