By Stan Miller

My students often ask what makes a portrait so appealing that one would buy a painting of someone they don’t know? In attempting to answer their question there are a number of things to consider. In my case, my style of painting portraits is traditional and realistic. I look for a model that has universal characteristics — one whose look suggests a type of character, rather than a face that has a very specific and unique look. I also look for a universal emotion — perhaps determination, intensity, sadness, or contemplation, rather than a face that shows a unique expression such as a sneer or a big grin.

My approach is analogous to a director who casts characters for a movie. If we compare this movie to my style of painting, the movie would have a traditional story with classic characters: the sad girl, the determined outsider, the sublime beauty, the lost soul, the mystic. If the viewer first sees and responds to the actor’s emotion and character, before they see the uniqueness and specificity of who they might be, their ability to relate will be more intimate and personal.

For those whose style of painting (or moviemaking) is more bizarre, impressionistic, or abstract, the need to pursue these guidelines diminish. The more abstracted the painting, the more one is open to imagine whomever one wants to imagine, and the mood becomes more open to interpretation. The painting materials and processes, like color, texture, uniqueness of approach, and energy of the technique, becomes a much greater consideration for liking the painting in the abstract, when compared to the realistic painting.

Another analogy to help us understand this idea might be writing. The more realistic the writing style, the more the characters need to be believable. The less realistic and more bizarre the story, the less one needs believable characters. As students and artists who choose to paint the portrait we first need to know just what it is we hope to communicate. Will our interpretation be essentially fiction or non-fiction?

If we have no desire to capture any specific truth that we may see in our model’s face when painting portraits, we could dismiss the model after an hour and for the next week we could simply work from our imagination. In using this approach we are probably heading towards Picasso. If we simply want to capture the truth of this face as the model appears to us as we paint, then we need an accurate drawing.

When the painting is finished, we hear the words, “It looks just like him (or her).” If we desire to paint the model as they look, but we wish to communicate a particular emotion or mood, we need to find the right model, direct the model and pose, pursue the right light, and edit the face and features as we paint. When we are finished, if we have been successful, we hear what we had hoped to capture: “She looks so sublime and contemplative;” rather than, “What’s her name?”

In writing, the professor asks us, “What do you want to say?” In portrait painting it’s equally important that we know what we wish to communicate. Most portrait artists who do commissions try to capture the truth about the specific person they are painting. In my work, I have little interest in capturing the particular truth of the specific person I am painting, but rather seek to communicate a particular emotion or truth about humanity. In Picasso’s work, the abstraction and distortion of the model permits viewers to share a wide variety of responses to his particular portrait. Fiction, non-fiction, the poem, the short story and the novel … so many ways to communicate a message, so many different styles, we need to choose and then commit ourselves to our chosen approach.

In the end, it’s all subjective art, and the artist has minimal control over understanding just why their art is accepted or rejected. The public, the critics, and in some cases, the centuries decide what is truly great art.

A COMMON TRUTH

It has been suggested that one of the primary reasons the Mona Lisa has endured in popularity through the centuries is because of her smile. Why her smile? Perhaps because she is not just smiling. Her smile seems to be uncertain, thoughtful, reflective, indecisive, causing one to pause, look again, ponder what she is thinking, feeling. There is a common truth that all of humanity shares and that we feel when we look at that smiling woman.

Picasso’s “Untitled” (1923) is so dramatically distorted and abstracted that one can quite easily imagine any number of characters and qualities of this person. The style and distortion of this painting is equal to or more fascinating than the subject (a smiling woman), diminishing the need to establish a more acceptable universal mood or character that a more realistic style might require.

The watercolor painting below is titled “Heather’s Memory.” My hope is that the viewer would first see her soul, her contemplative thoughtfulness and longing. If people’s initial reaction to this painting is, “What’s her name?,” the painting in my mind would be a failure (except for her family).

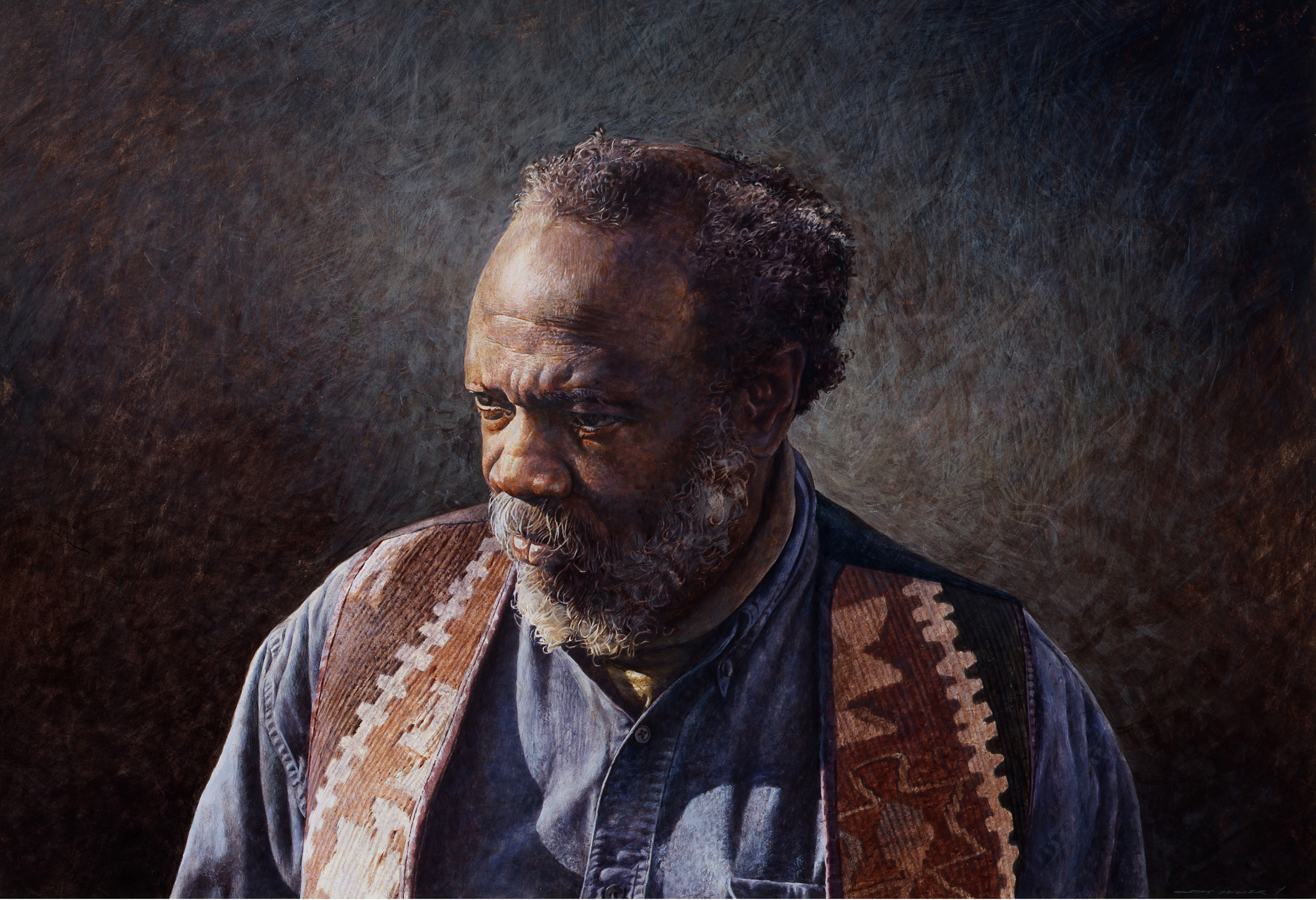

“Charles” is painted with egg tempera on paper. My goal was for the viewer to first see the contemplative man — a man who ponders life and reflects on his family, his history, his past, his future.

With “The Messenger,” do we first want to know who this person is? Or do we first want to know what he is feeling, what he is looking at, what he might be reading? The character on his face suggests that he has struggled in life, that there are storms around him, and yet we might see a courage . . . a strength.

Finding the right model, creating the right lighting and doing effective editing are all crucial in communicating the right message. Determine the viewer response you hope to achieve before choosing a subject and starting your watermedia portrait. Keeping this goal in mind will focus your attention on only the details that move the painting in that direction.

Learn more about Stan Miller at www.stanmiller.net.