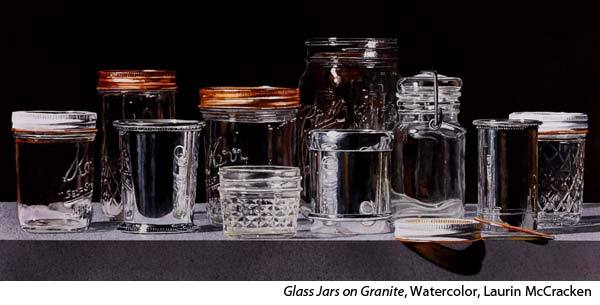

You can’t paint the details unless you can see the details. I find one of the most difficult things to teach my workshop students is to look more closely at an object and see the details. They look at a cut crystal bowl and see the roundness of the bowl and some cuts on the side, but they don’t look closely enough at those lines in the bowl to understand how they were created and therefore how to paint them.

You also have to forget what you think something looks like to realize what it really looks like. You have to connect your brush with your eyeball and bypass your brain.

It also makes a big difference if you have the right tools. I mostly use rounds. I started out using 0 and 00 size rounds. Then I was shown that #4 top-grade kolinsky rounds, such as Escoda’s Reserva line, can make as fine a line as a 0, and they hold a lot more paint.

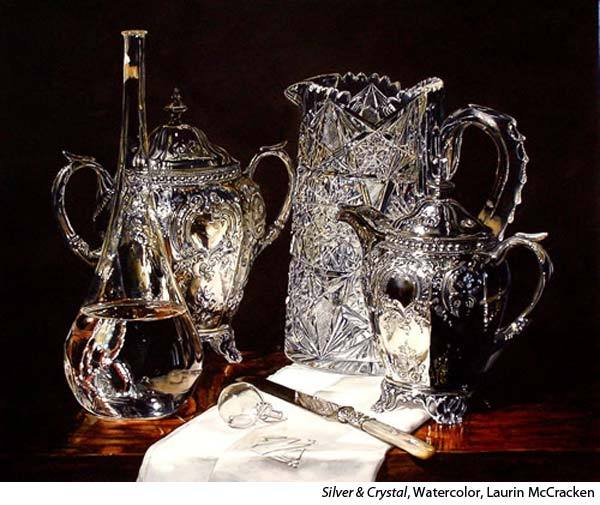

Painting on the proper surface also makes a big difference. I use Fabriano Artistico soft-pressed paper. It is smooth enough so that it will hold the detail, but soft enough to allow you to work the paint into the paper to create the roundness of a silver teapot.

The Opposite of Fast and Loose

I have often said that watching me paint must be about as exciting as watching grass grow. While many of my watercolor friends believe that if they are spending more than an hour on a painting they are wasting their time, my paintings often take 100 hours or more. The more I look at something the more detail I see and the more detail I want to paint.

If you are going to paint a high degree of realism, in any medium and especially in watercolor, you cannot do it quickly. Often, I have to adjust my expectations of how much detail I can paint because it is not physically possible, or I would never finish anything. I use the time that I am painting to listen to music, plan my next move in the painting I am working on, plan my next marketing strategy or solve the problems of the universe.

Assembling a Still Life

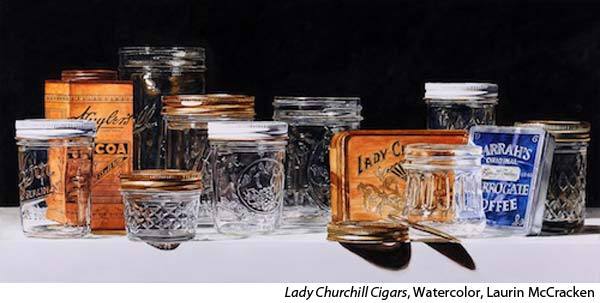

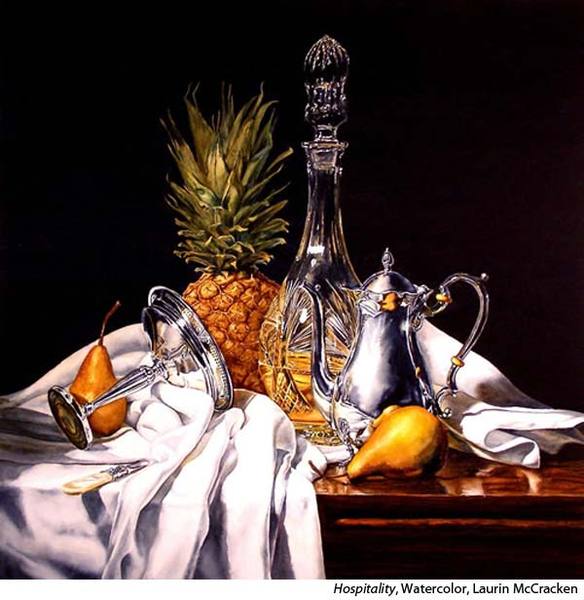

Creating an interesting story about the objects is the goal of a good still life composition. The correct placement of the objects and the correct lighting can help the viewer’s appreciation of how the objects are created. The placement in the objects can tell the viewer something about the relative relationship between the objects.

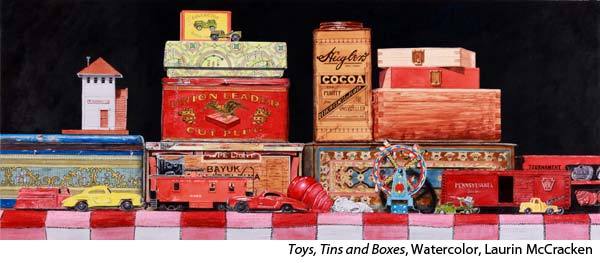

I use every approach in designing a still life composition. Sometimes I see an object and immediately think of a still life setup. This happened when I returned from the grocery store with apples, pears and a roll of aluminum foil. That became a series of paintings of fruit on aluminum foil.

Recently, I did a thumbnail sketch of some bottles and turned that into a still life setup. Sometimes the object just leads me to an assemblage that works as a painting as in Toys, Tins and Boxes.

As I assemble objects for my still life paintings I am always thinking about certain design principles such as “an odd number of objects is more interesting than an even number” and “the best lighting for a still life comes from the left.”

Many of these “rules” are so ingrained in my thinking that I don’t consciously think of them. They just happen.

One of the things I must always be conscious of is the juxtaposition of objects in still life, especially the adjacencies. If one object is in the foreground and another is in the background, but from the viewers point of view they seem to be almost touch, the viewer can not tell which is forward and which is further back. Simply moving the most forward object so that it overlaps the object behind it allows the viewer a greater ease in understanding the placement of the objects in the still life.

While every still life comes together in its own peculiar way, there is a basic approach I take in creating a still life.

I set up my background, with or without a piece of cloth or a piece of lace. I then start with three simple objects. I use them to determine the best placement for my light. I typically use only one light source. I move the objects around to try and improve the general composition. I also turn them to determine where how the light best strikes the object. I use the light increase the dimensionality of the objects.

At each move or turn I will probably take an image. The great thing about digital photography is that each image is very inexpensive and fast.

Then I start adding more objects sometimes one or two at a time, constantly moving and turning them to create a more interesting composition and to react to the light and the relative position to each of the other objects. Many times, I will get to the point where I have too many objects in the photo and too much going on in the setup and then I will start eliminating objects until the most ideal composition comes together.

Working From Photos

I only work from photographs. When I started painting in watercolor, I painted flowers. I quickly learned that if I was going to paint in a highly realistic style the flowers would not live long enough, so I started taking photographs and painting from them.

Now, many times, the availability I had to someone’s fine, heirloom silver and crystal was only long enough to set up a still like and take multiple photos. It might be months or even years later until I had the opportunity to paint these objects. I am still working from photos I took 5 years ago and more.

I agree that you don’t have to be a slave to your photos. I often move things when drawing the still life for the final painting to improve the placement of objects in the painting.

I spend a lot of time and am very careful about setting up and photographing my reference photos. Many times, the photographs become works of art in and of themselves. While many of my photographs of silver and crystal are taken in other people’s homes, in my home I use my guest bedroom to photograph still life setups. I have the right lighting, a collection of cloth and lace for backgrounds as well as an ever-expanding collection of props to use in my creating the still lifes.

Moving From Photo to Paper

I put all the images in my computer and then go through them, full screen, and eliminate the obviously poor shots. Then I will select out those that have the best possibility for becoming a painting.

I have learned that not all good photos make great paintings. I then narrow the best images down to two or there and think about them for a while, sometimes months. I will then go back to these images and make prints of them and think some more.

When I finally make my choice, I will move the image onto a portable memory device and project them onto my watercolor paper using a very high-resolution projector. I will then trace as much of the image onto the paper as is possible. Here is where I often find some weak adjacencies. From there I will move my paper to my painting board and add the last of the details to the drawing. I usually make large prints of the image, 13 x 17 inches, and I will paint from those prints. The drawing process for a full sheet painting can take four to six hours.

Laurin McCracken shares more of his still life painting process in Watercolor Realism: Glass & Wood With Laurin McCracken. No matter what subject you like to paint, if realism is your aim, we’ve got you covered with demos and presentations from more than 20 top artists at Realism Live!