Some artists swear by reference photos; others only work from sketches. Watercolor artist William G. Hook demonstrates how to combine the best of both worlds in no-fail composition studies:

“Your camera is where you gather data to help you understand and remember what inspired you about a subject. Your sketchbook is your personal visual laboratory where you plan your successes and hide your failures. This is where you make visual notes, record, and test your ideas and develop them into great paintings.

“Thumbnail sketches are not just pretty little pictures in your sketchbook. These small studies are powerful tools to plan the success of your paintings. At this scale, you can easily and quickly study and make critical decisions about the BIG issues of composition, values, and light, which are the foundation of a compelling painting. If your small study doesn’t catch your attention, it certainly won’t be compelling when it is larger.

A successful thumbnail will be a reliable reference to avoid major problems and uncertainty later when you’re well into a large painting. Details and accurate layout issues can be addressed at full scale without losing the power and essence of your initial inspiration.

Getting the “Big Out There” Into Your Sketchbook

“Sketching directly on site is a valuable skill to develop, but often we don’t have the time or skills to effectively record what we are seeing. We take tons of pictures, which help record stuff but usually these pictures end up in our files, and we forget what inspired us at the time. To keep the inspiration alive, we need to do something creative with the images.

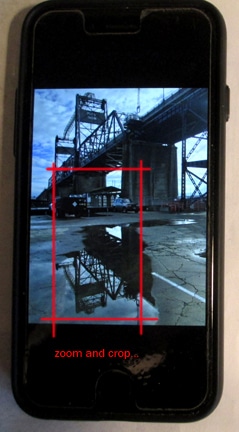

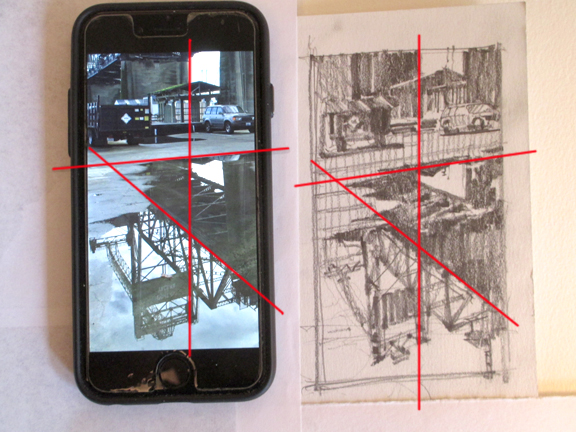

“Your camera display is an ideal way to get images into your sketchbook. The display is a good size to study a subject. Once you have zoomed in and out, and cropped the photo to focus on an area you like, it’s easier to make a study about the same size. Main shape, perspective lines, and angles are simple to duplicate and in only a few minutes you have a thumbnail sketch. Once you have done something like this with a photo, you will always remember what inspired you in the first place, and you can then proceed with studying values, playing with light, and moving elements around to make a better composition.

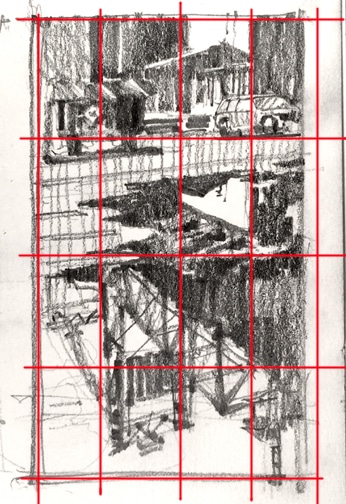

“To transfer your thumbnail to your watercolor paper, draw a grid on your sketch and a larger grid on your sheet of watercolor paper. At this point, you can add in all of the details needed and proceed with the painting. Keep referring back to the sketch to consult the values and light patterns.

Poor Photos Can Make Great Paintings

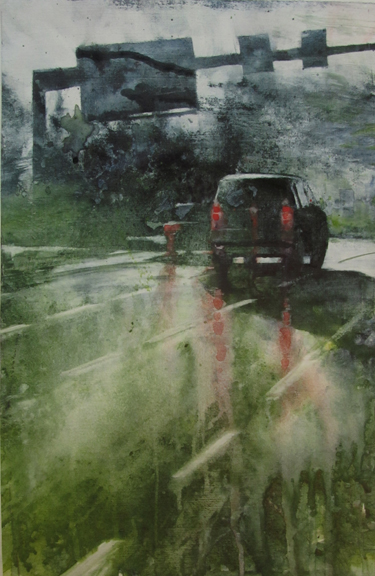

“I am a firm believer in bad photos. Some of my best paintings have been based on blurry, gray, or underexposed photos. They allow me to focus on the essence of the subject and my inspiration without being distracted by information overload. Some of my greatest disasters were the result of trying to compete with a beautiful, fully detailed and perfect photo.

“An out of focus or dark photo can reveal strong shapes and compositions on which to build a new vision. Oftentimes I find my best composition in the fuzzy background of a photo. In Formwork 6 (below) I was drawn to the overall shape of the formwork in the distance. The specific details of the bracing were not critical to the overall image. I just needed to add light in the background to bring it to life.

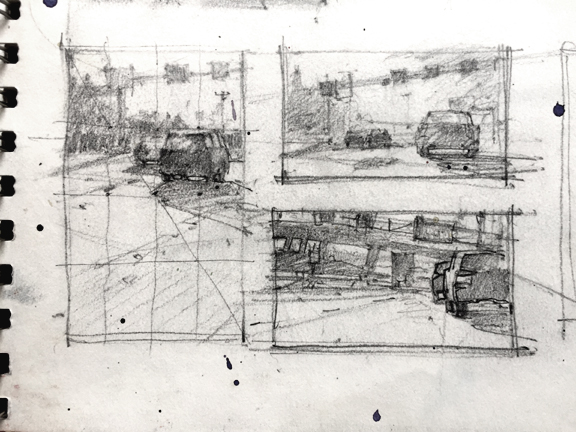

“Below is another example of a poor photo, which had an interesting area in the mid-ground. I studied several layouts before I settled on the small vertical. These studies only took 10 to 15 minutes to create, but I was able to solve my composition and value issues effectively.

Get to Know Your Subject

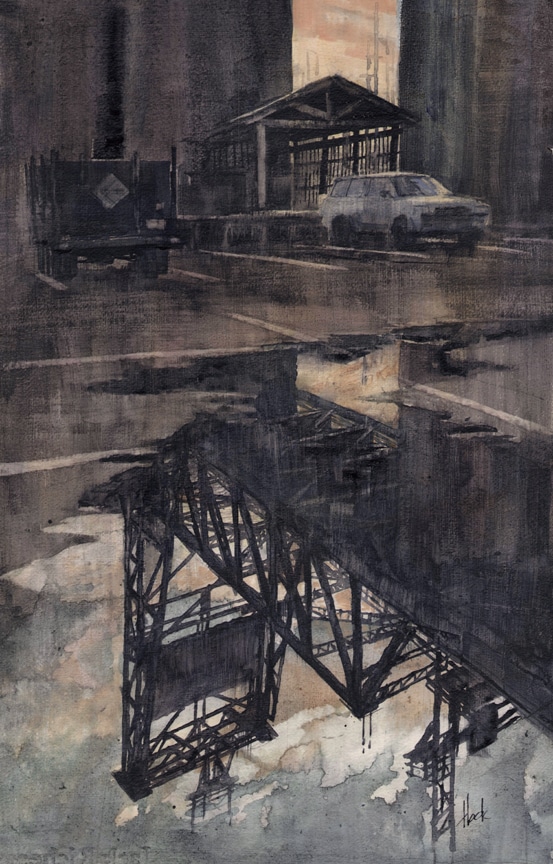

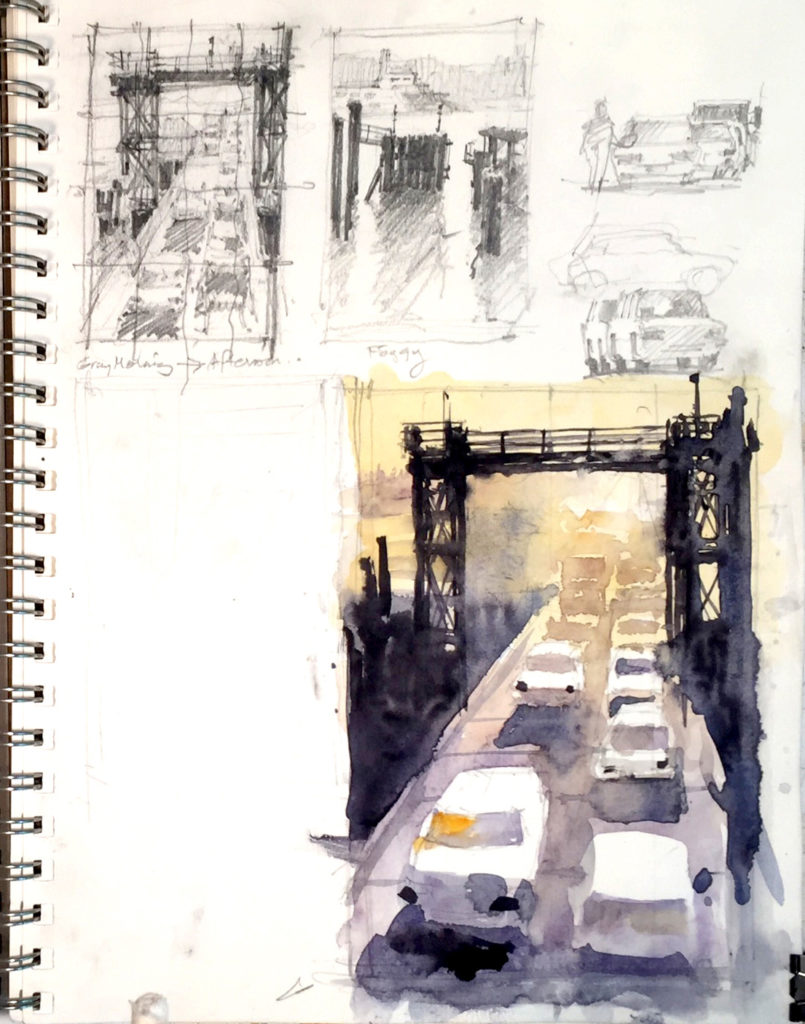

“I always try to walk around my subject to better understand it. Frequently, I find that the backside of my subject is more interesting than the front. Walking around a subject, I also get acquainted with the its surroundings; what I see has an effect on how I feel and respond to the subject. I pay special attention to the light. My first look at this bridge with the light in front looks busy and rather normal—a nice sunny morning but nothing outstanding. As I walked around the bridge, I found it was much more powerful against the light sky. The trusses were less chaotic and simpler, and best of all, I found great reflections in puddles left from the morning rain.

Dealing With Information Overload

“Use thumbnail studies to simplify and record the essence of an image. The picture of the ferry loading dock was confusing and overly complex with weak light, giving it a flat feeling. The essence for me was the portal structure and the line of cars trailing into the background. I changed the proportions and simplified the portal in my pencil study, then did a quick color study to capture a warm light source in the background. This page in my sketchbook has effectively recorded my inspiration in a form that I can build on if I choose to develop a larger more finished painting in the future. The sketch has a grid, which allows for redrawing it larger, and the color study has recorded the light as well as the simplification of detail in the background. I can always add more detail as needed, but the power and values of the picture are clearly apparent at this size. This one is ready and waiting to become a successful painting when I get to it.

Timing is Important. Get Something Down as Soon as You Can.

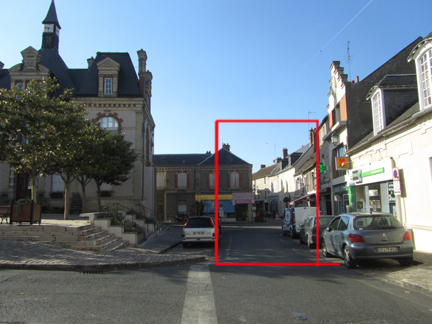

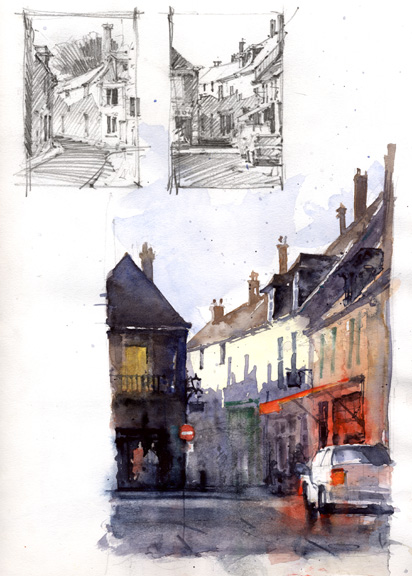

“Here is another picture from a trip to France. I didn’t have time to sit down and paint at the time, but I managed to take a couple of pictures. Later that evening in my hotel room, while my memory was fresh, I made a couple of pencil studies from the display on my camera. The main building and plaza were nice, but I was most interested in the shadows on the buildings along the small street in the background. Timing is important. Try to make some sort of notes as soon as possible after taking pictures before the inspiration fades.

“Now I have another page waiting for me in my sketchbook with all of the important information that I’ll need to rekindle my inspiration when I get a chance to take it to the next level.”

William G. Hook is an award-winning watercolor artist.

For more inspiring stories like this one, sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

I love seeing the initial photo, the thumbnail sketch, and then the painting. I plunge in before my ideas are clear so your steps show me a way to overcome this bad habit. Thanks.