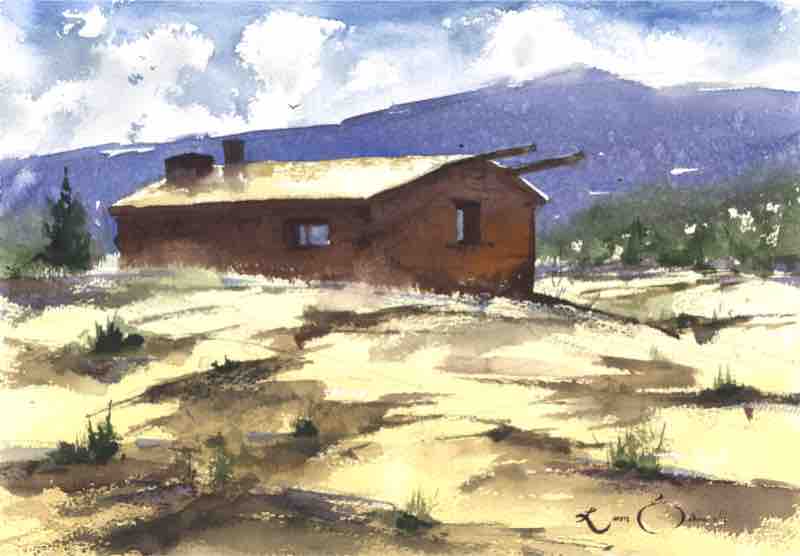

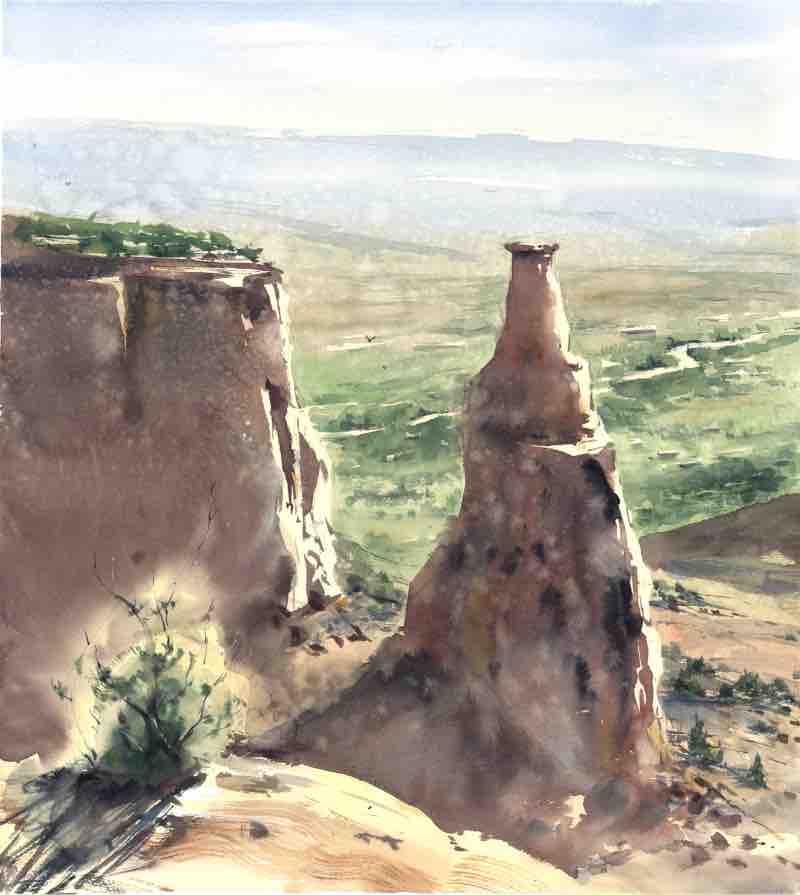

A biologist and painter, Loren Eakins uses the observational skills of both fields to paint the truth in the landscape. Unsurprisingly, he takes care to understand the natural elements in the scenes he depicts. He’s done work in scientific illustration, which places a high premium on accurate detail and technical precision. “Doing that, you have to understand the structure of a flower or how one species of ray differs from another, for example,” he says. His attendance in the BFA program at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design, in Denver, meant three years of figure drawing. “You have to know the musculature and anatomy of a human to really understand and paint the figure,” he says. “Likewise, you have to know how a plant grows to paint it well. A big part of painting something well is understanding what you’re looking at. Then you can use brushstrokes that describe the structure.”

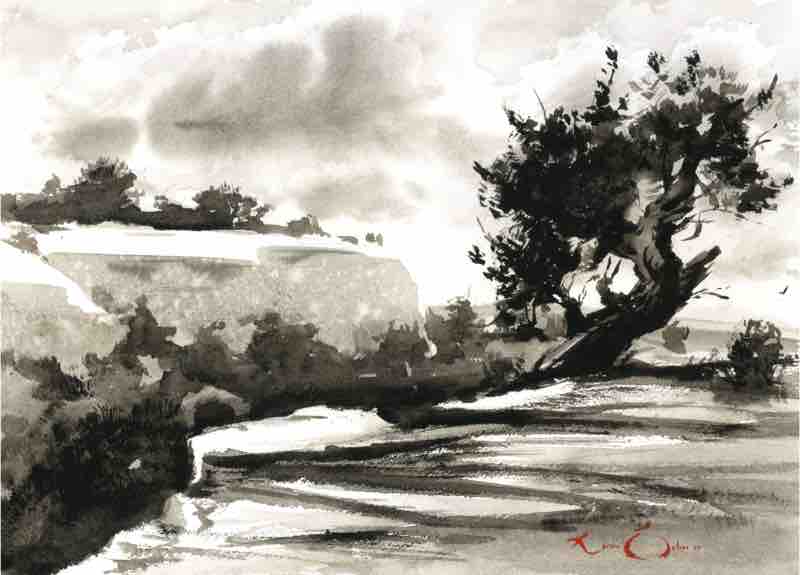

Those brushstrokes are made in watercolor with a variety of brushes, including big mops, hog fans, and Chinese calligraphy brushes. For Eakins, watercolor is a sort of bridge between drawing and oil painting, his other passions. When he breaks the “rules” of a given medium, it’s usually because the transgression is orthodoxy in a different medium. For example, his darks are often thicker than his lights, as they usually are in watercolor technique — the opposite of the traditional approach in oil, where thick highlights of light color signal the finish of a painting. And Eakins says he loves painting in watercolor using ivory or bone black on white watercolor paper, using a squirrel-hair brush — like a drawing. “It’s a really good way to paint with values and think beyond color,” he says. He has the following advice for people interested in his watercolor approach: “The darks are determined by the viscosity of your paint. With black paint, in the classical Eastern style, the thickness of the paint determines the value. Think of the darkest as being like butter or cream, the middle range running like milk, and the lightest light having the consistency of thin coffee or tea.”

In “The Barbara Tapp Watercolor Method,” Barbara Tapp share her own non-traditional process that starts with placing her dark shadow shapes first to achieve maximum contrast. Follow along so see how her “reverse” process can give you a new and exciting way to analyze a scene, exposing you to new patterns, contrasts, and textures to add drama to your paintings!