By Ken Karlic

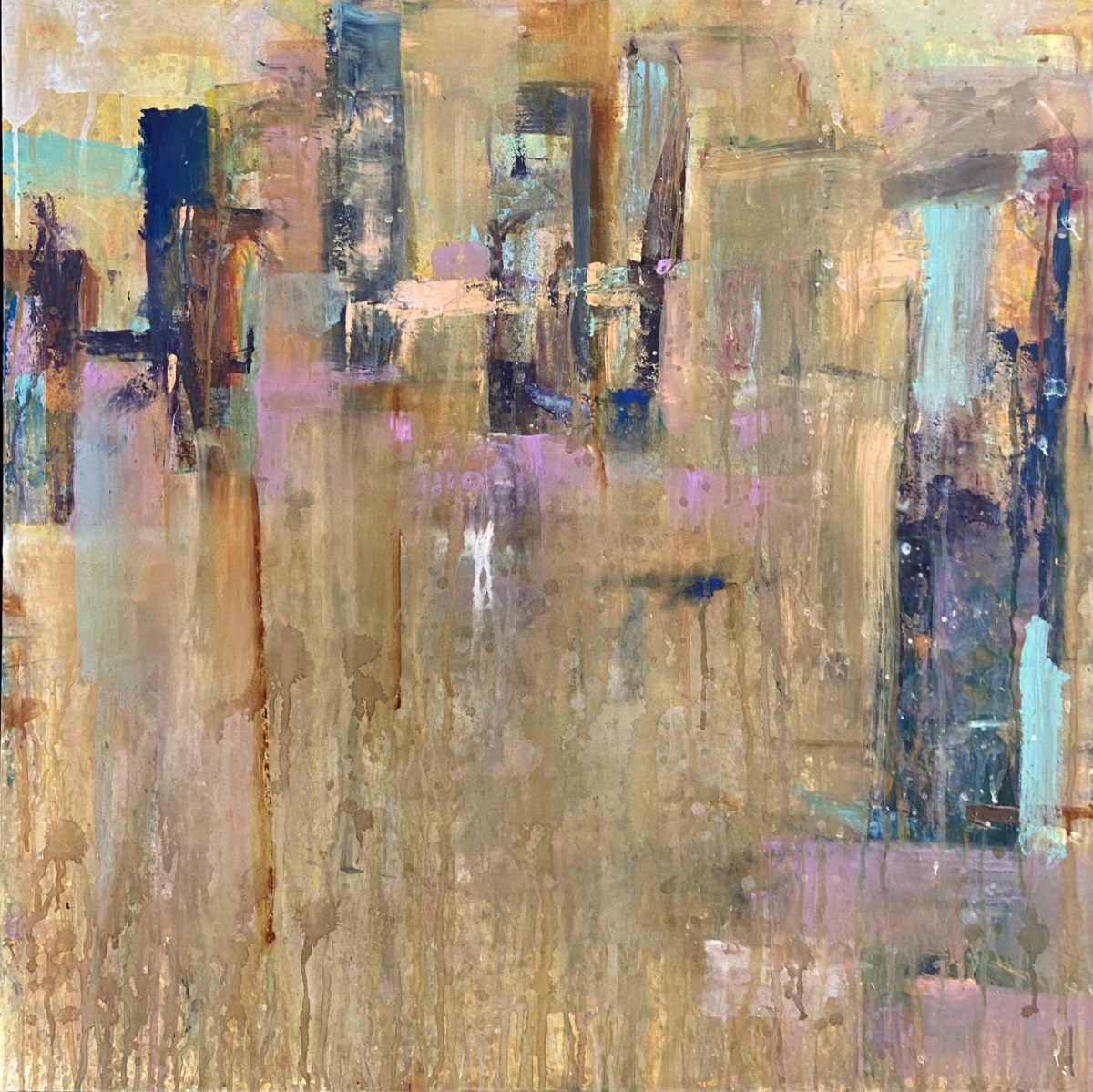

As my work has developed, my style and methodology seem to be about “more” — more scale, more paint, more water, more effects, more everything. I found that as the work got larger, my painting gestures got larger, and my handling of the paint got wilder. I love how watercolors behave — and misbehave, granulating beautifully, especially on a larger scale. To accommodate the new surface size, I now paint from my shoulder rather than my wrist, and the movements have become more free and gestural. I find that painting larger allows for more adventure, and also provides more room for experimentation.

MORE SCALE

In general, watercolor paintings are modest in scale, generally a quarter or a half sheet (11 x 15 and 15 x 22 inches respectively), but usually not larger than a full sheet (22 x 30 inches). For years, I painted within these sizes, in a more representational style. Ultimately, I became less satisfied with how I was working so I looked for something more meaningful and more personal to bring to my work. I began to embrace greater ambiguity in my paintings, and as a result, they took a dramatic turn toward the abstract.

I experimented with various surface sizes, and quickly found myself working on 36 x 36, 30 x 50, and 30 x 60-inch papers. As my work scaled up, the biggest challenge I faced was managing the surface. The sheer real estate often felt daunting, and using a small or medium watercolor brush ultimately gave way to using 2 to 4-inch bristle brushes from Home Depot. In general, I approach painting at this size very differently, giving myself the freedom to mix transparent with opaque, and light with dark, without regard to the traditional watercolor painting process. Whether en plein air or in the studio, I find it liberating to work large and give give the painting the space it deserves.

MORE PAINT

Traditionally, painters have turned to watercolor for its transparent qualities, and to gouache when they need an opaque watermedia. I paint with both, but use watercolors as much for their opacity as their transparency. I use a lot of paint, much more than most watercolorists I imagine, and would compare my technique more to that of an oil painter.

Most often I allow my colors to mix and mingle right on the painting surface, or build up them up on my brush before applying them to the paper, rather than pre-mix them on my palette. I vary my applications, from thick, gooey strokes to watery mixtures. I build brush marks into layers and add water, which can turn a simple brushstroke into one that can drip for three feet. I also squeeze paint directly out of the tube, or apply it with a variety of tools to achieve a cake-like application. Once it’s applied, I often introduce a stream of water to break things up and distribute remnants of the color.

When it comes to gouache, I only use the color white, which can be used straight out of the tube for an opaque quality, or mixed with various amounts of water to achieve different consistencies, resulting in a range of transparencies. Mixed with water, white gouache behaves rather recklessly, creating unique effects unlike anything else — it can spatter, streak, brush, drip, and more. Used both ways, the medium has become critical to my work.

MORE WATER

The essence of watercolor painting is the relationship between water and paint— it’s about manipulating quantities of one in relation to the other. For any watercolorist, water is what makes the paint fluid enough to apply it to the substrate. In my work, water becomes a much more active player. As I start a painting, I mix up and apply a slurry of paint. At this point water is my most valuable tool. I can spray or drizzle it from above and let it run through the paint to create channels of texture, or encourage any number of other interesting interactions to take place on the paper. I can also use it to scrub the paint with a brush or my hands to create surface variety.

Even while the surface is drying, I introduce water at various stages, deconstructing portions of the painting by using water on my fingers, brushes, or other tools to wipe sections or edges out. In the end, I might use up to three gallons of water per sitting, with most paintings demanding multiple sittings.

Ken Karlic shares more about his process and the inspiration behind his bold watercolors in the February-March issue of PleinAir Magazine.