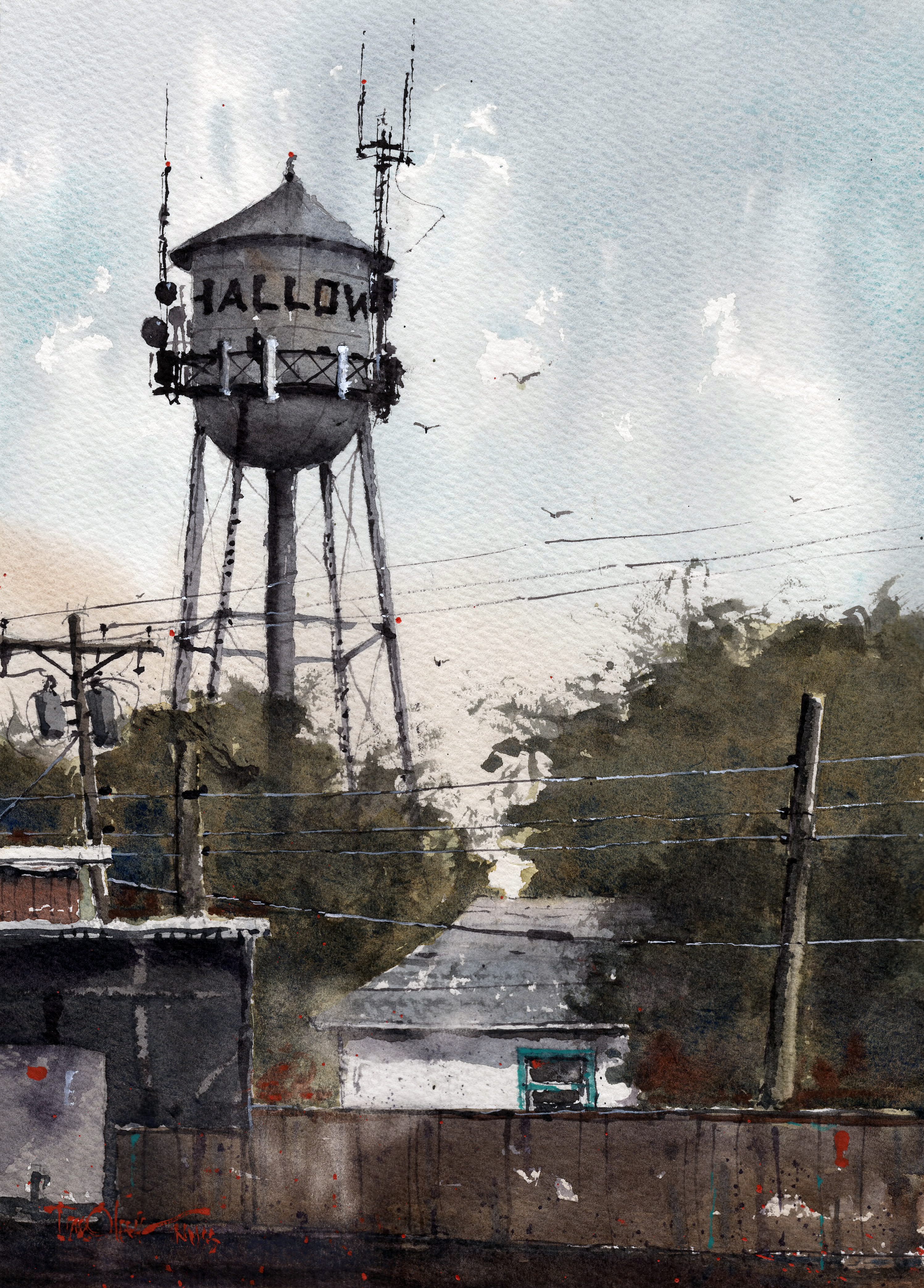

First introduced to watercolor by a friend in college, Tim Oliver fell in love with the transparency and color-blending qualities of the medium. A landscape architect by trade, he also has a reputation as a top-notch plein air watercolor painter, describing his style as “sloppy representationalism.”

Kelly Kane: How do you feel your day job in landscape architecture impacts your plein air work? What are the sensibilities that crossover?

Tim Oliver: Being in a design profession, I’m accustomed to drawing and sketching, so I’ve always felt very comfortable communicating graphically with a pencil and paper. I think I was actually drawn to landscape architecture for the graphic component of the job; it certainly wasn’t the technical side — the math and all that. I believe there’s a shared skill set in being able to see context in a place. In my landscape architecture, I’m trying to communicate the character of a place that I’m designing. With my watercolors, I’m interpreting an existing landscape in a fine art context. Both relate to conveying a sense of place.

Kane: Do you have favorite places to paint en plein air — spots that draw you back again and again?

Oliver: I tend to always be looking for the next thing, the next subject. On occasion, I have gone back to the same location multiple times. But when I’m done with a place, I tend to be done with it. I’m constantly on the prowl for something new; I want to move on and see what’s next.

Kane: What kinds of subjects most appeal to you?

Oliver: I was raised on a cotton farm, so the land is really important to me. Today I live in the high plains of West Texas, which is flat with no elevated landforms. It’s primarily an agricultural region. We’ve got 180 degrees of sky and flat horizons. What always makes me want to pull over to the side of the road and paint is a landscape with a story— either a story that’s going on now or a story that happened in the past. I’m attracted to places where big skies and long horizons intersect with where man has been or is currently. It’s the abandoned farmhouse or grain elevator, or it’s the working grain elevator, with lots of activity around it. It’s not the majestic mountains, rivers, streams, and beaches that people love to paint. The subjects I’m attracted to are more mundane maybe, but I’m drawn to those stories — real or imagined. I see an old farmhouse and I wonder, Who lived there? Were they happy? What tragedies did they live through in their lives? Somebody once told me, “You know, you paint the things most of us would just drive right by.” I don’t know if he meant it as a compliment, but I took it as one.

Another top watercolor artist Andy Evansen shares his techniques for leading the viewer’s eye, using darks to design a scene, creating believable reflections, painting skies effectively, making use of spontaneous brushstrokes, and more in Andy Evansen: Secrets of Painting Watercolor Outdoors.

Lovely work Tim!

From the way you handle your paint I suspect it doesn’t matter what you paint. I like them all.

Nice story and point. It’s not what you paint. It’s how you paint it (for the most part). An accomplished artist could paint an alleyway with a dumpster on a cloudy day and make it look good.

Superb work 👍