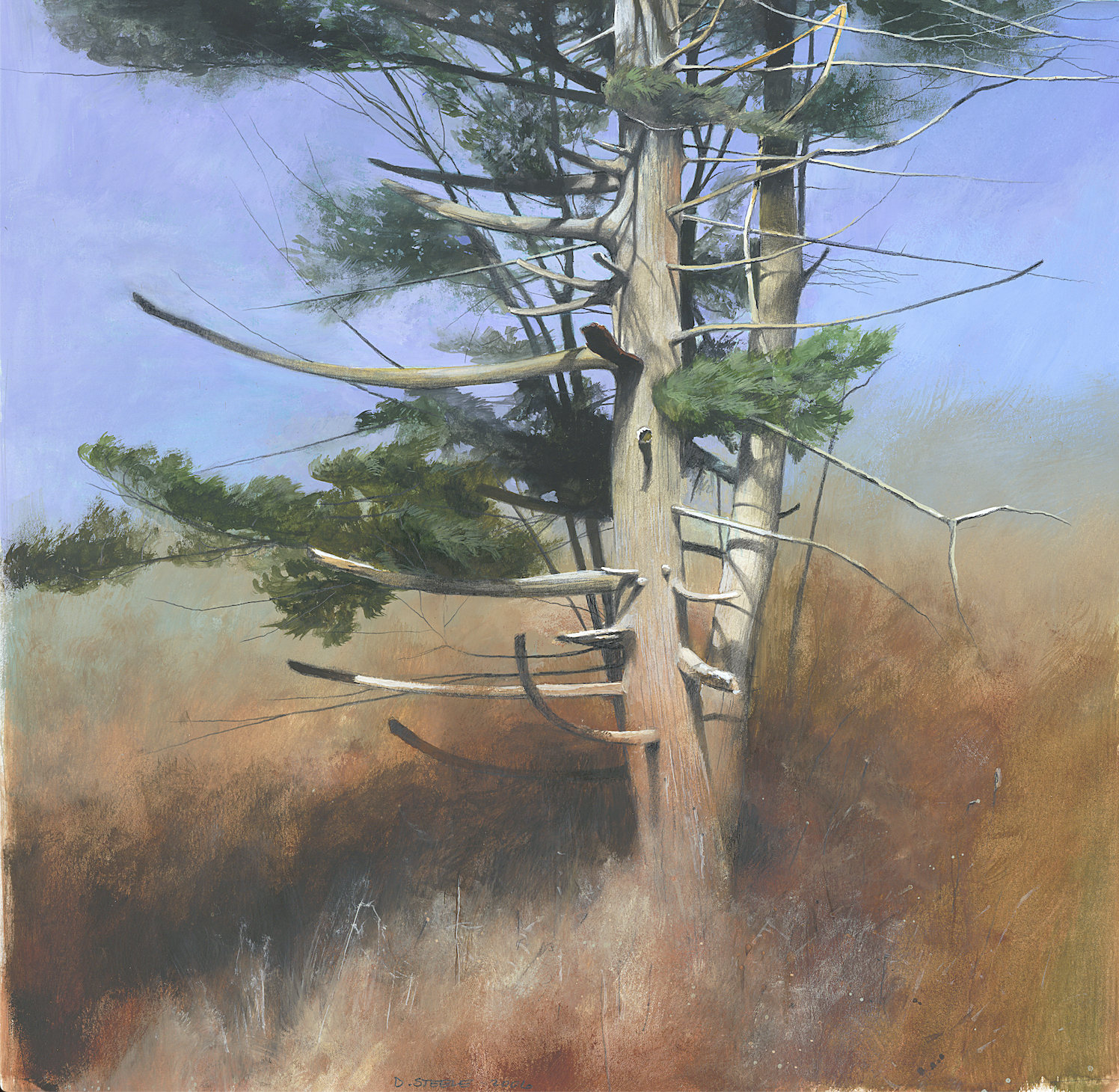

“Concerning my approach to my subject, it is not simply the rendition of objects, trees, rocks, flowers, or still life,” says Darryl Glenn Steele. “Instead, my concern is painting the moment — the ambiance and the light — to capture the essence of my subject. I want my audience to experience the same attraction to my painting that I felt when I first had the desire to paint it.

“It seems to me that I have always been an artist. I can’t imagine ever being happy doing anything else and I cannot remember a time when art was not a part of my life. Since childhood I have had the desire to draw and paint. I remember epic battles in far away lands full of dinosaurs drawn on rolls of butcher paper pulled out of early classroom closets, the feel of tempera paint on multi-colored construction paper, and the smell of a newly opened box of crayons. And now, after all of these years, as I watch my grandchildren explore the world of art, I have come to realize that whatever it is within us that causes us to have the desire to create is something that we all are born with. I think that all children are artists and maybe all artists are still children in a way. I am sure that whether it be painting, sculpting, drawing, writing, music, dance, architecture, or film, the one thing that we all as artists have in common is that spark of inspiration within, and it is only the mediums and processes that differentiate one artist from another.

“Looking back, I doubt that my seventh grade art teacher ever said more than two words to me, but from the time we entered his classroom until the bell rang, we sat in the darkened room and practiced drawing day in and day out. I owe him a debt of gratitude for he was the one who drummed it into my head that if you wanted to be an artist you had to learn to draw. Drawing is more than just hand-eye coordination, it is, in one word, “understanding.” I remember a Wyeth exhibition that came to town a few years ago. In the exhibit were several pencil drawings of Christine’s withered arm. Wyeth knew that before he could paint Christine’s World he would have to understand her withered arm. I am convinced that he knew as much about the anatomy of her arm as any surgeon. I make this point only to emphasize the importance of knowing your subject. Good writer’s say “write what you know,” well I think the same goes painters . . . paint what you know.

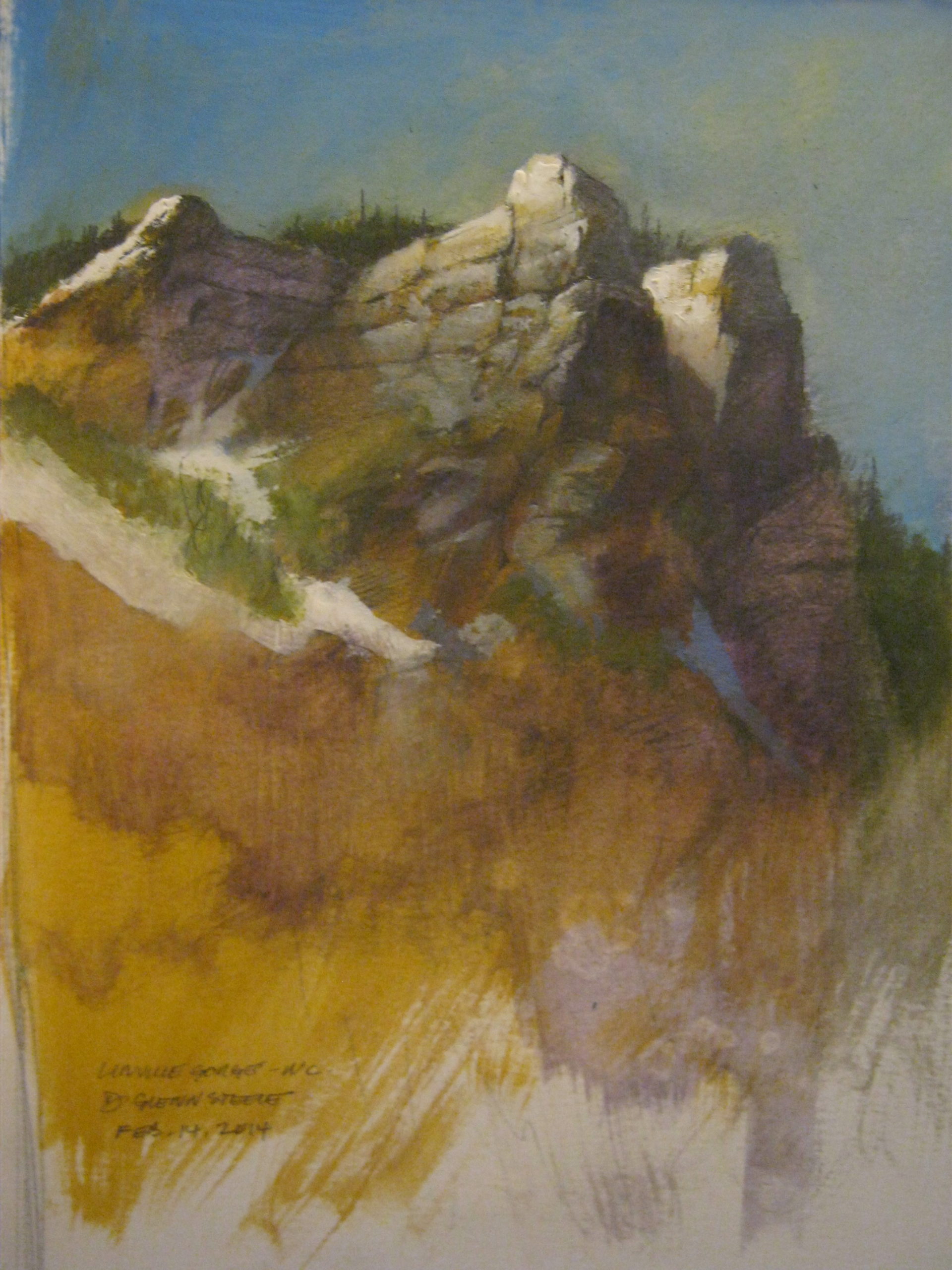

“I consider myself a ‘self-taught’ artist, only because I have had a limited formal education in the arts, but I have learned something from every artist that I have encountered during my lifetime, so the term “self-taught” does not really fit. Over the years I have studied the work of other painters and incorporated their techniques into my own work and out of this devotion my own style seems to have magically appeared. From my early years as an oil painter to my love of watercolor today, I have graduated into combining the techniques of both into my work. I find it difficult to articulate just how I go about painting these days, because I don’t have a set of rules or formulas. Instead each painting has its own requirements. I may begin a painting with watercolor and then glaze over it with oil, or use acrylics for an underpainting, or sometimes even use a tissue paper collage to create texture. I paint on paper, canvas, mat board, masonite, or whatever substrate I have at hand, and I have even been known to use spray paint, or paint into oil with gouache. The point is that when it comes to how I approach a painting — all rules are made to be bent, and or, sometimes … broken. For me it is the end and not the means that matter.

“That said, I am a traditional painter in the sense that my work is representational — although it does border on the abstract from time to time. I keep my compositions simple — to the point that I think I have tunnel vision. When I paint, all of the work and focus will go into the center of interest and everything else is subdued, or merely suggested — sometimes beyond recognition, and it’s not on purpose, because once I have captured what I feel is the heart of my subject then I feel like all else has become pointless. I have the tendency to focus all of my energy on one point and then everything else just fades away like a memory, or a moment in time, a feeling, or perhaps just a glimpse of something that I caught out of the corner of my eye. What I strive to communicate in my work is what I like to call the “indescribable mystery” — that feeling when inspiration sparks into flame. To communicate to the viewer the reason why I wanted to paint the subject in the first place; to let others see and feel what I see and feel. After all, isn’t that what art is all about? It is true you know, a picture is worth a thousand words, and the way I write, maybe much more.”

One of the best places to record what you see and feel is in your sketchbook. The relaxation it brings is meditative. You’re free to do anything in your private sketchbook — experiment, be inventive, try new techniques, create whole new worlds within its pages. In High Level Sketching, award-winning artist Iain Stewart shows you how to recreate the experience in your studio with his approach to painting-as-sketching.