MARY CASSATT (American, 1844-1926)

Mary Cassatt spent her adult life in France, where she became an integral part of the Impressionist group. Cassatt was born into an affluent family who first protested against her desire to become an artist. She eventually left art school after being frustrated by the separate treatment that the female students received — they couldn’t use live models and were left drawing from casts.

Upon moving to Paris at age 22, Cassatt sought a private apprenticeship and spent her free time copying Old Master paintings in the Louvre. Cassatt’s career was already taking off when she joined the Impressionists and forged a lifelong friendship with Degas. At the same time, she was outspoken in her dismay at the formal art system, which she felt required female artists to flirt or befriend male patrons in order to move ahead. She created her own career path with the Impressionists, creating work that often highlighted women acting as caretakers. Throughout her life, Cassatt continued to support equality for women, even participating in an exhibition in support of women’s suffrage.

Cassatt painted this self-portrait, one of only two known, a year after Edgar Degas invited her to exhibit with the Impressionists. His influence is apparent in the unusual sage-green background, the attention to contrasting complementary colors, and the figure’s daring and casual asymmetrical pose. Louisine Elder (later Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer), a young American art student Cassatt met in Paris in 1874, acquired this work by 1879. Havemeyer would become Cassatt’s great friend and American patron, donating much of her impressionist collection to Metropolitan Museum of Art.

BERTHE MORISOT (French, Bourges 1841–1895)

Considered one of the great female Impressionists, Berthe Morisot had art running through her veins. Born into an aristocratic French family, she was the great-niece of celebrated Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Initially, she exhibited her work at the respected Paris Salon before joining the first Impressionist exhibit with Monet, Cézanne, Renoir, and Degas. Morisot has a particularly close relationship with Édouard Manet, who painted several portraits of her, and she eventually married his brother.

Her art often focused on domestic scenes and she preferred working with pastels, watercolor, and charcoal. Working mainly in small scale, her light and airy work was often criticized as being too “feminine.” Morisot wrote about her struggles to be taken seriously as a female artist in her journal, stating “I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal and that’s all I would have asked for, for I know I’m worth as much as they.”

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE (American, 1887- 1986)

As an artist at the forefront of American Modernism, Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the most celebrated female artists in history. Her early drawings and paintings led to bold experiments in abstraction, with her focus on painting to express her feelings ushering in an era of “Art for Art’s Sake.” During her lifetime, her career was intertwined with her husband, Alfred Stieglitz. While the renowned photographer espoused ideas that American art could equal that of Europe and that female painters could create art just as powerful as men, he also hindered interpretation of her work.

Stieglitz viewed creativity as an expression of sexuality and these thoughts, coupled with his intimate portraits of O’Keeffe, pushed forward an idea that her close up paintings of flowers were metaphors for female genitalia. It’s a concept that the artist had always denied, though her work is undoubtedly sensual. O’Keeffe spent much of her career combatting her art’s interpretation solely as a reflection of her gender. Throughout her life she refused to participate in all-female art exhibitions, wishing to be defined simply as an artist, free from gender.

FIDELIA BRIDGES (American, 1834-1923)

One of the few women to have a successful art career in the late 19th century, Fidelia Bridges was known for delicately detailed paintings that captured flowers, plants, and birds in their natural settings. Although she began as an oil painter, she later gained a reputation as an expert in watercolor painting. She was the only woman among a group of seven artists in the early years of the American Watercolor Society. Some of her work was published as illustrations in books and magazines and on greeting cards.

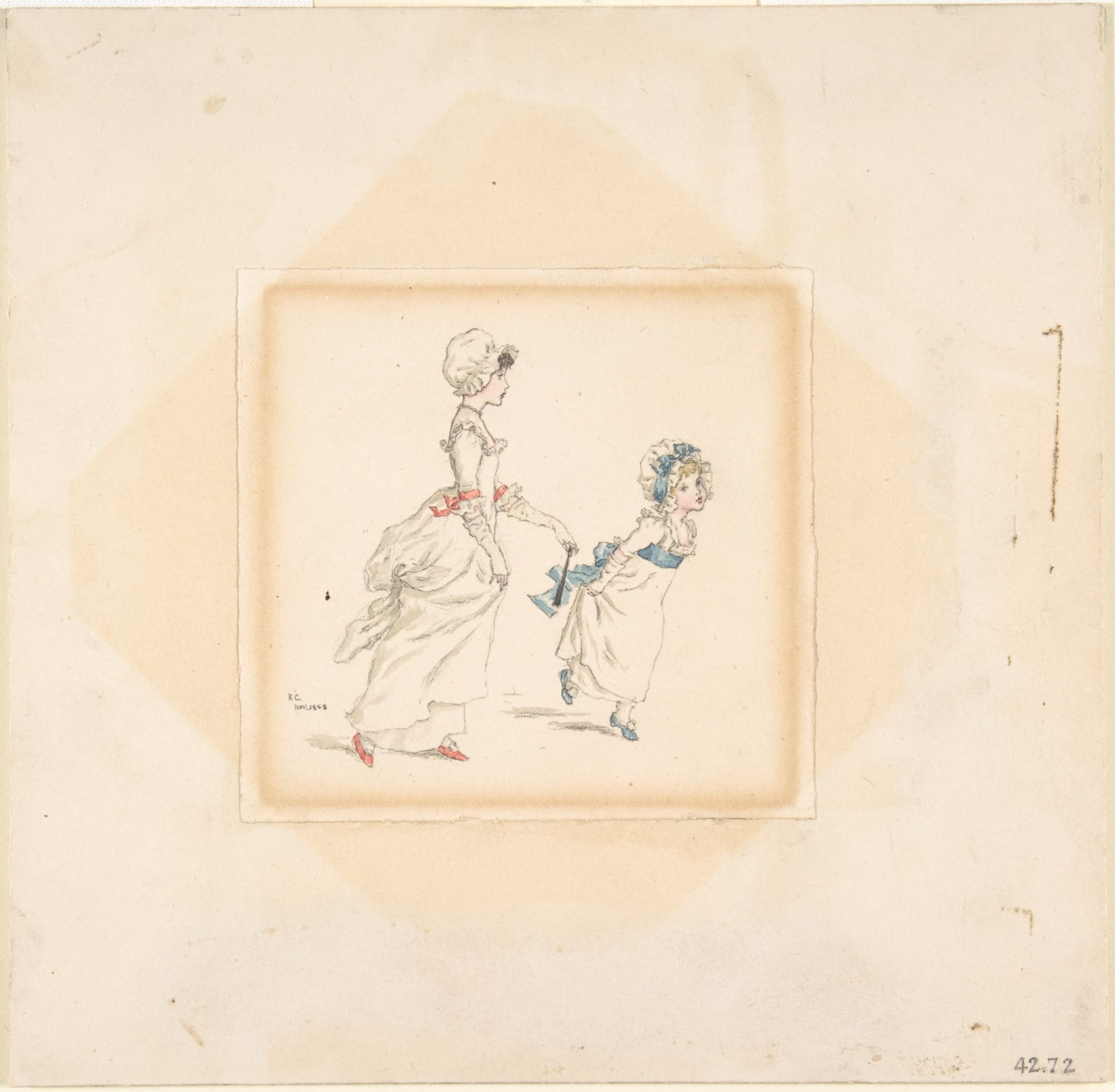

KATE GREENAWAY (British, 1846–1901)

Catherine Greenaway was an English Victorian artist and writer, known for her children’s book illustrations. She received her education in graphic design and art between 1858 and 1871 from South Kensington School of Art and the Royal Female School of Art, and the Slade School of Fine Art. She began her career designing for the burgeoning holiday card market, producing Christmas and Valentine’s cards. In 1879, woodblock engraver and printer, Edmund Evans, printed Under the Window, an instant best-seller, which established her reputation. Her collaboration with Evans continued throughout the 1880s and 1890s.

The depictions of children in imaginary 18th-century costumes in a Queen Anne style were extremely popular in England and internationally, sparking the Kate Greenaway style. Within a few years of the publication of Under the Window Greenaway’s work was imitated in England, Germany and the United States.

For more inspiring stories like this one, sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Applause” “Apause” for celebrating women artists! I hope this could become a regular article.

I’m so pleased to see Fidelia Bridges included. Her work is exquisite!

look forward to and enjoy this every week.

Would like to see Emily Carr included. Much to the dismay of her family, she chose to leave a privileged life in the 1800’s to paint artifacts and surroundings of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific northwest in Canada. She became one of the so-called Canadian “Group of Seven” artists.

As a woman I am grateful for the attention to such fine artists as these. But I stand with Georgia O’Keeffe in that art should be judged not on the basis of the creator’s gender but on the merits of the work. Thank you for your good work.

It would be great to do this again this year for women’s history month with LIVING artists