Joyce Hicks starts with photo references, but has learned when to put them away and let her creativity take over.

“When I first started painting the landscape, I was overwhelmed with all of the information out there,” says Joyce Hicks. “So I devised a simple method for distilling the landscape.”

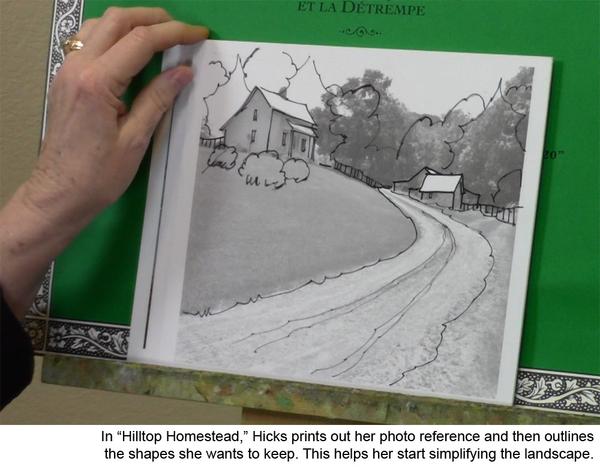

For Hicks, it all starts with shifting her thinking from seeing objects as things to seeing objects as shapes. Instead of seeing a barn or a tree, she sees a rectangle and a triangle. To help, she prints out her photo reference in black and white, then uses a sharpie to outline the shapes she wants to include in her painting.

VALUE STUDY/COLOR STUDY

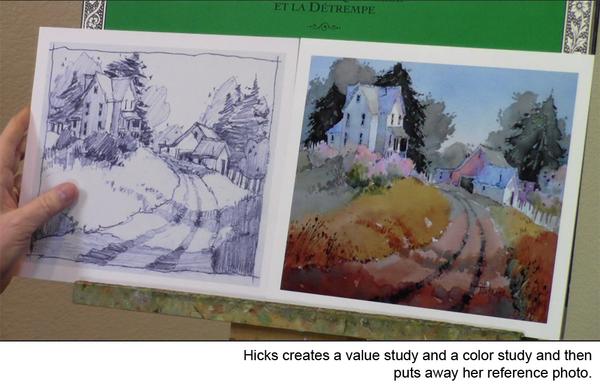

Once she has her shapes, she works on a compositional and value study in her small 6 x 6-inch sketchbook. Often, she’ll combine elements from several photographs to create a stronger design. “I’ll take artistic license and rearrange the shapes, keeping only what I like,” she says. “And I will dismiss what I don’t like.”

After her value study, she creates a small color study based on those values. “I don’t ever paint from a photograph — it will lead you down the wrong path every time. You want to be an artist, not a human camera” she says. She takes liberty with color, turning even a boring scene into something dynamic by amping up the colors.

THE PAINTING

With the preparatory work done, Hicks puts the photo away and begins her drawing. “The first thing we have to decide is how do we want to start and where do we want to start,” she says. “I always make a plan before I put paint on my brush.” She suggests drawing a sun on the edge of the tape holding your watercolor paper onto your board to represent where the light source lives in the sky. You’ll always want the sun’s location to be top of mind.

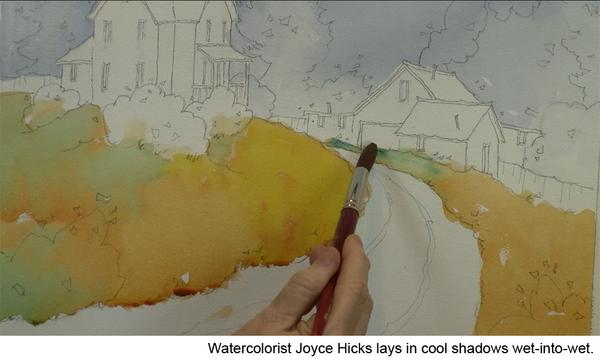

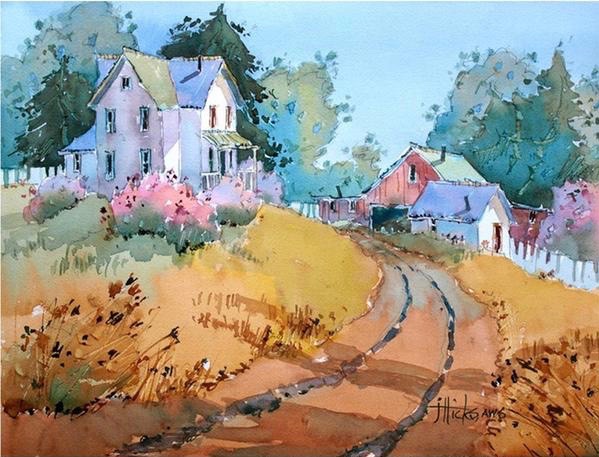

The artist begins her painting by laying in her first washes. While the golden fields are still damp, she lays in manganese blue for the shadows and yellow for the sunlit areas. The result is an immediate sense of sunlight and shadow all with lovely soft edges.

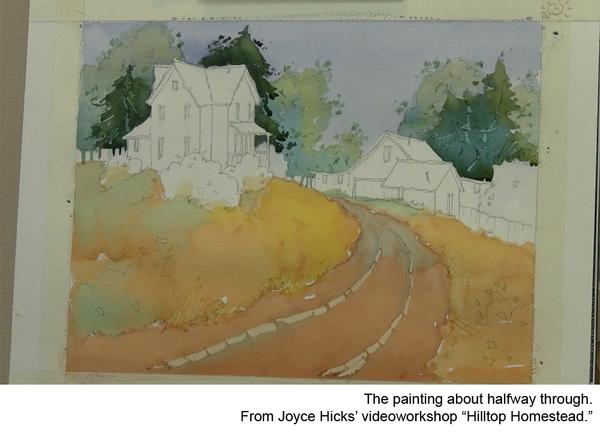

Hicks finishes her washes and then begins to work from the background to the foreground. She starts with her trees, bushes, buildings, and the shadows.

There’s a rhythm to how Hicks works. She pauses before each section and decides what she’s going to do next. Mostly that’s a conversation about placement. She’s constantly thinking about how close a shape (representing an object) is to the viewer and how that will affect the color value, temperature, and intensity of that shape. Hicks works in groups, so she does all the similar trees at the same time, for example. This way, she can be conscious about her treatment of them. Again, she decides which one is closest to the viewer; that tree gets the most saturated and the warmest color.

This way of grouping and painting like-objects is a useful way to work for someone still learning. It limits the number of decisions you have to make and once you figure out the plan, you can use that plan across the whole section before wrapping it up and letting it be.

Hicks works most of the painting wet-into-wet, first mixing color on her palette and then dropping in additional color to adjust the temperature or intensity, or just to add interest.

SUNLIGHT AND SHADOW

“You have to identify what you love about the scene, and then you need to exaggerate it. If the painting is about the sunny day, then exaggerate the sunshine,” she says.

Joyce Hicks shares her entire process in her video workshop, “Hilltop Homestead: Transforming the Landscape in Watercolor.”

Yes, I took a 3 day workshop from Joyce Hicks I Clearwater, Florida about 6 years ago. A wonderful teacher and a fantastic artist.

I won one of her original demo paintings and love it.

Thank you Joyce for a memorable learning experience.

Barbra Joan

Hi Kelly, I just noticed! Thank you for sharing my four easy steps for transforming the landscape here on American Watercolor!…Joyce Hicks, AWS